Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | JFM |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 246 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 36 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 23 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Thu, 15 Dec 2016

Let's decipher a thousand-year-old magic square

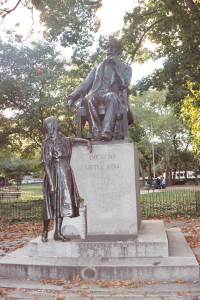

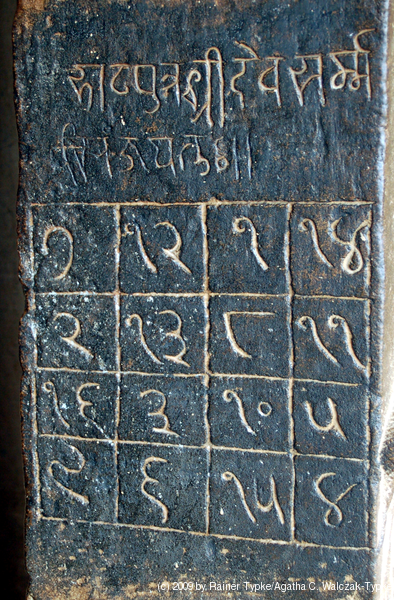

The Parshvanatha temple in Madhya Pradesh, India was built around 1,050 years ago. Carved at its entrance is this magic square:

The digit signs have changed in the past thousand years, but it's a quick and fun puzzle to figure out what they mean using only the information that this is, in fact, a magic square.

A solution follows. No peeking until you've tried it yourself!

There are 9 one-digit entries

and 7 two-digit entries

so we can guess

that the entries are the numbers 1 through 16, as is usual, and the

magic sum is 34. The  appears in the

same position in all the two-digit numbers, so it's the digit 1. The

other digit of the numeral

appears in the

same position in all the two-digit numbers, so it's the digit 1. The

other digit of the numeral  is

is  , and this must be zero. If it were

otherwise, it would appear on its own, as does for example the

, and this must be zero. If it were

otherwise, it would appear on its own, as does for example the

from

from  or the

or the

from

from  .

.

It is tempting to imagine that  is 4.

But we can see it's not so. Adding up the rightmost column, we get

is 4.

But we can see it's not so. Adding up the rightmost column, we get

+

+  +

+  +

+  =

=

+ 11 +

+ 11 +  +

+  =

=

(10 +  ) + 11 +

) + 11 +  +

+  = 34,

= 34,

so that  must be an odd number. We

know it isn't 1 (because

must be an odd number. We

know it isn't 1 (because  is 1), and it

can't be 7 or 9 because

is 1), and it

can't be 7 or 9 because  appears in the

bottom row and there is no 17 or 19. So

appears in the

bottom row and there is no 17 or 19. So  must be 3 or 5.

must be 3 or 5.

Now if  were 3, then

were 3, then  would be 13, and the third column would be

would be 13, and the third column would be

+

+  +

+  +

+  =

=

1 +  + 10 + 13 = 34,

+ 10 + 13 = 34,

and then  would be 10, which is too big. So

would be 10, which is too big. So  must be 5, and this means that

must be 5, and this means that  is 4 and

is 4 and  is 8.

(

is 8.

( appears only a as a single-digit

numeral, which is consistent with it being 8.)

appears only a as a single-digit

numeral, which is consistent with it being 8.)

The top row has

+

+  +

+  +

+  =

=

+

+  + 1 + 14 =

+ 1 + 14 =

+ (10 +

+ (10 +  ) + 1 + 14 = 34

) + 1 + 14 = 34

so that  +

+  = 9.

= 9.  only appears as a single digit and

we already used 8 so

only appears as a single digit and

we already used 8 so  must be 7 or 9.

But 9 is too big, so it must be 7, and then

must be 7 or 9.

But 9 is too big, so it must be 7, and then  is 2.

is 2.

is the only remaining unknown single-digit

numeral, and we already know 7 and 8, so

is the only remaining unknown single-digit

numeral, and we already know 7 and 8, so

is 9. The leftmost column tells us

that

is 9. The leftmost column tells us

that  is 16, and the last two entries,

is 16, and the last two entries,

and

and  are

easily discovered to be 13 and 3. The decoded square is:

are

easily discovered to be 13 and 3. The decoded square is:

|

|

I like that people look at the right-hand column and immediately see 18 + 11 + 4 + 8 but it's actually 14 + 11 + 5 + 4.

This is an extra-special magic square: not only do the ten rows, columns, and diagonals all add up to 34, so do all the four-cell subsquares, so do any four squares arranged symmetrically about the center, and so do all the broken diagonals that you get by wrapping around at the edges.

[ Addendum: It has come to my attention that the digit symbols in the magic square are not too different from the current forms of the digit symbols in the Gujarati script. ]

[ Addendum 20161217: The temple is not very close to Gujarat or to the area in which Gujarati is common, so I guess that the digit symbols in Indian languages have evolved in the past thousand years, with the Gujarati versions remaining closest to the ancient forms, or else perhaps Gujarati was spoken more widely a thousand years ago. I would be interested to hear about this from someone who knows. ]

[ Addendum 20170130: Shreevatsa R. has contributed a detailed discussion of the history of the digit symbols. ]

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link

Mon, 12 Dec 2016

Another Git catastrophe cleaned up

My co-worker X had been collaborating with a front-end designer on a very large change, consisting of about 406 commits in total. The sum of the changes was to add 18 new files of code to implement the back end of the new system, and also to implement the front end, a multitude of additions to both new and already-existing files. Some of the 406 commits modified just the 18 back-end files, some modified just the front-end files, and many modified both.

X decided to merge and deploy just the back-end changes, and then, once that was done and appeared successful, to merge the remaining front-end changes.

His path to merging the back-end changes was unorthodox: he checked

out the current master, and then, knowing that the back-end changes

were isolated in 18 entirely new files, did

git checkout topic-branch -- new-file-1 new-file-2 … new-file-18

He then added the 18 files to the repo, committed them, and published

the resulting commit on master. In due course this was deployed to

production without incident.

The next day he wanted to go ahead and merge the front-end changes,

but he found himself in “a bit of a pickle”. The merge didn't go

forward cleanly, perhaps because of other changes that had been made

to master in the meantime. And trying to rebase the branch onto the

new master was a complete failure. Many of those 406 commits included

various edits to the 18 back-end files that no longer made sense now

that the finished versions of those files were in the master branch

he was trying to rebase onto.

So the problem is: how to land the rest of the changes in those 406 commits, preferably without losing the commit history and messages.

The easiest strategy in a case like this is usually to back in time:

If the problem was caused by the unorthodox checkout-add-commit, then

reset master to the point before that happened and try doing it a

different way. That strategy wasn't available because X had already

published the master with his back-end files, and a hundred other

programmers had copies of them.

The way I eventually proceeded was to rebase the 406-commit work

branch onto the current master, but to tell Git meantime that

conflicts in the 18 back-end files should be ignored, because the

version of those files on the master branch was already perfect.

Merge drivers

There's no direct way to tell Git to ignore merge conflicts in exactly

18 files, but there is a hack you can use to get the same effect.

The repo can contain a .gitattributes file that lets you specify

certain per-file options. For example, you can use .gitattributes

to say that the files in a certain directory are text, that when they

are checked out the line terminators should be converted to whatever

the local machine's line terminator convention is, and they should be

converted back to NLs when changes are committed.

Some of the per-file attributes control how merge conflicts are resolved. We were already using this feature for a certain frequently-edited file that was a list of processes to be performed in a certain order:

do A

then do B

Often different people would simultaneously add different lines to the end of this file:

# Person X's change:

do A

then do B

then do X

# Person Y's change:

do A

then do B

then do Y

X would land their version on master and later there would be a

conflict when Y tried to land their own version:

do A

then do B

<<<<<<<<

then do X

--------

then do Y

>>>>>>>>

Git was confused: did you want new line X or new line Y at the end of the file, or both, and if both then in what order? But the answer was always the same: we wanted both, X and then Y, in that order:

do A

then do B

then do X

then do Y

With the merge attribute set to union for this file, Git

automatically chooses the correct resolution.

So, returning to our pickle, I wanted to set the merge attribute for

the 18 back-end files to tell Git to always choose the version already

in master, and always ignore the changes from the branch I was

merging.

There is not exactly a way to do this, but the mechanism that is provided is extremely general, and it is not hard to get it to do what we want in this case.

The merge attribute in .gitattributes specifies the name of a

“driver” that resolves merge conflicts. The driver can be one of a

few built-in drivers, such as the union driver I just described, or

it can be the name of a user-supplied driver, configured in

.gitconfig. The first step is to use .gitattributes to tell Git

to use our private, special-purpose driver for the 18 back-end files:

new-file-1 merge=ours

new-file-2 merge=ours

…

new-file-18 merge=ours

(The name ours here is completely arbitrary. I chose it because its

function was analogous to the -s ours and -X ours options of

git-merge.)

Then we add a section to .gitconfig to say what the

ours driver should do:

[merge "ours"]

name = always prefer our version to the one being merged

driver = true

The name is just a human-readable description and is ignored by Git.

The important part is the deceptively simple-appearing driver = true

line. The driver is actually a command that is run when there is

a merge conflict. The command is run with the names of three files

containing different versions of the target file: the main file

being merged into, and temporary files containing the version with the

conflicting changes and the common ancestor of the first two files. It is

the job of the driver command to examine the three files, figure out how to

resolve the conflict, and modify the main file appropriately.

In this case merging the two or three versions of the file is very

simple. The main version is the one on the master branch, already

perfect. The proposed changes are superfluous, and we want to ignore

them. To modify the main file appropriately, our merge driver command

needs to do exactly nothing. Unix helpfully provides a command that

does exactly nothing, called true, so that's what we tell Git to use

to resolve merge conflicts.

With this configured, and the changes to .gitattributes checked in,

I was able to rebase the 406-commit topic branch onto the current

master. There were some minor issues to work around, so it was not

quite routine, but the problem was basically solved and it wasn't a

giant pain.

I didn't actually use git-rebase

I should confess that I didn't actually use git-rebase at this

point; I did it semi-manually, by generating a list of commit IDs and

then running a loop that cherry-picked them one at a time:

tac /tmp/commit-ids |

while read commit; do

git cherry-pick $commit || break

done

I don't remember why I thought this would be a better idea than just

using git-rebase, which is basically the same thing. (Superstitious anxiety,

perhaps.) But I think the process and the result were pretty much the

same. The main drawback of my approach is that if one of the

cherry-picks fails, and the loop exits prematurely, you have to

hand-edit the commit-ids file before you restart the loop, to remove the commits that were

successfully picked.

Also, it didn't work on the first try

My first try at the rebase didn't quite work. The merge driver was

working fine, but some commits that it wanted to merge modified only

the 18 back-end files and nothing else. Then there were merge

conflicts, which the merge driver said to ignore, so that the net

effect of the merged commit was to do nothing. But git-rebase

considers that an error, says something like

The previous cherry-pick is now empty, possibly due to conflict resolution.

If you wish to commit it anyway, use:

git commit --allow-empty

and stops and waits for manual confirmation. Since 140 of the 406 commits modified only the 18 perfect files I was going to have to intervene manually 140 times.

I wanted an option that told git-cherry-pick that empty commits were

okay and just to ignore them entirely, but that option isn't in

there. There is something almost as good though; you can supply

--keep-redundant-commits and instead of failing it will go ahead and create commits

that make no changes. So I ended up with a branch with 406 commits of

which 140 were empty. Then a second git-rebase eliminated them,

because the default behavior of git-rebase is to discard empty

commits. I would have needed that final rebase anyway, because I had

to throw away the extra commit I added at the beginning to check in

the changes to the .gitattributes file.

A few conflicts remained

There were three or four remaining conflicts during the giant rebase, all resulting from the following situation: Some of the back-end files were created under different names, edited, and later moved into their final positions. The commits that renamed them had unresolvable conflicts: the commit said to rename A to B, but to Git's surprise B already existed with different contents. Git quite properly refused to resolve these itself. I handled each of these cases manually by deleting A.

I made this up as I went along

I don't want anyone to think that I already had all this stuff up my sleeve, so I should probably mention that there was quite a bit of this I didn't know beforehand. The merge driver stuff was all new to me, and I had to work around the empty-commit issue on the fly.

Also, I didn't find a working solution on the first try; this was my second idea. My notes say that I thought my first idea would probably work but that it would have required more effort than what I described above, so I put it aside planning to take it up again if the merge driver approach didn't work. I forget what the first idea was, unfortunately.

Named commits

This is a minor, peripheral technique which I think is important for everyone to know, because it pays off far out of proportion to how easy it is to learn.

There were several commits of interest that I referred to repeatedly while investigating and fixing the pickle. In particular:

- The last commit on the topic branch

- The first commit on the topic branch that wasn't on

master - The commit on

masterfrom which the topic branch diverged

Instead of trying to remember the commit IDs for these I just gave

them mnemonic names with git-branch: last, first, and base,

respectively. That enabled commands like git log base..last … which

would otherwise have been troublesome to construct. Civilization

advances by extending the number of important operations which we can

perform without thinking of them. When you're thinking "okay, now I

need to rebase this branch" you don't want to derail the train of

thought to remember where the bottom of the branch is every time.

Being able to refer to it as first is a big help.

Other approaches

After it was all over I tried to answer the question “What should X

have done in the first place to avoid the pickle?” But I couldn't

think of anything, so I asked Rik Signes. Rik immediately said that

X should have used git-filter-branch to separate the 406 commits

into two branches, branch A with just the changes to the 18 back-end

files and branch B with just the changes to the other files. (The

two branches together would have had more than 406 commits, since a

commit that changed both back-end and front-end files would be

represented in both branches.) Then he would have had no trouble

landing branch A on master and, after it was deployed, landing

branch B.

At that point I realized that git-filter-branch also provided a less

peculiar way out of the pickle once we were in: Instead of using my

merge driver approach, I could have filtered the original topic branch

to produce just branch B, which would have rebased onto master

just fine.

I was aware that git-filter-branch was not part of my personal

toolkit, but I was unaware of the extent of my unawareness. I would

have hoped that even if I hadn't known exactly how to use it, I would

at least have been able to think of using it. I plan to

set aside an hour or two soon to do nothing but mess around with

git-filter-branch so that next time something like this happens I

can at least consider using it.

It occurred to me while I was writing this that it would probably have

worked to make one commit on master to remove the back-end files

again, and then rebase the entire topic branch onto that commit. But

I didn't think of it at the time. And it's not as good as what I did

do, which left the history as clean as was possible at that point.

I think I've written before that this profusion of solutions is the sign of a well-designed system. The tools and concepts are powerful, and can be combined in many ways to solve many problems that the designers didn't foresee.

[Other articles in category /prog] permanent link

Thu, 08 Dec 2016An earlier article discussed how I discovered that a hoax item in a Wikipedia list had become the official name of a mountain, Ysolo Mons, on the planet Ceres.

I contacted the United States Geological Survey to point out the hoax, and on Wednesday I got the following news from their representative:

Thank you for your email alerting us to the possibility that the name Ysolo, as a festival name, may be fictitious.

After some research, we agreed with your assessment. The IAU and the Dawn Team discussed the matter and decided that the best solution was to replace the name Ysolo Mons with Yamor Mons, named for the corn/maize festival in Ecuador. The WGPSN voted to approve the change.

Thank you for bringing the matter to our attention.

(“WGPSN” is the IAU's Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature. Here's their official announcement of the change, the USGS record of the old name and the USGS record of the new name.)

This week we cleaned up a few relevant Wikipedia articles, including one on Italian Wikipedia, and Ysolo has been put to rest.

I am a little bit sad to see it go. It was fun while it lasted. But I am really pleased about the outcome. Noticing the hoax, following it up, and correcting the name of this mountain is not a large or an important thing, but it's a thing that very few people could have done at all, one that required my particular combination of unusual talents. Those opportunities are seldom.

[ Note: The USGS rep wishes me to mention that the email I quoted above is not an official IAU communication. ]

[Other articles in category /wikipedia] permanent link

Thu, 24 Nov 2016

Imaginary Albanian eggplant festivals… IN SPACE

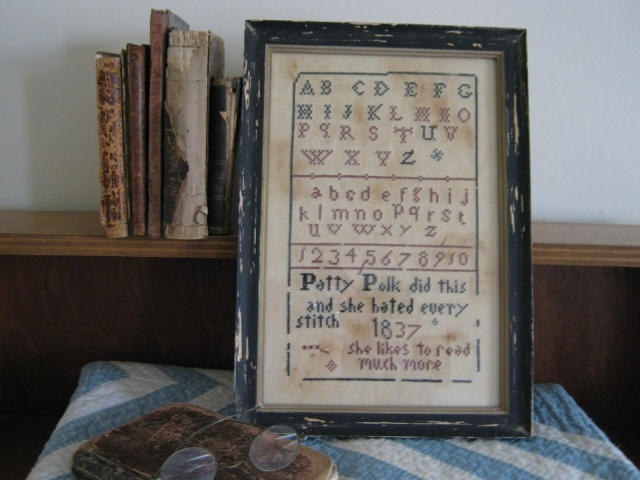

Wikipedia has a list of harvest festivals which includes this intriguing entry:

Ysolo: festival marking the first day of harvest of eggplants in Tirana, Albania

(It now says “citation needed“; I added that yesterday.)

I am confident that this entry, inserted in July 2012 by an anonymous user, is a hoax. When I first read it, I muttered “Oh, what bullshit,” but then went looking for a reliable source, because you never know. I have occasionally been surprised in the past, but this time I found clear evidence of a hoax: There are only a couple of scattered mentions of Ysolo on a couple of blogs, all from after 2012, and nothing at all in Google Books about Albanian eggplant celebrations. Nor is there an article about it in Albanian Wikipedia.

But reality gave ground before I arrived on the scene. Last September NASA's Dawn spacecraft visited the dwarf planet Ceres. Ceres is named for the Roman goddess of the harvest, and so NASA proposed harvest-related names for Ceres’ newly-discovered physical features. It appears that someone at NASA ransacked the Wikipedia list of harvest festivals without checking whether they were real, because there is now a large mountain at Ceres’ north pole whose official name is Ysolo Mons, named for this spurious eggplant festival. (See also: NASA JPL press release; USGS Astrogeology Science Center announcement.)

To complete the magic circle of fiction, the Albanians might begin to celebrate the previously-fictitious eggplant festival. (And why not? Eggplants are lovely.) Let them do it for a couple of years, and then Wikipedia could document the real eggplant festival… Why not fall under the spell of Tlön and submit to the minute and vast evidence of an ordered planet?

Happy Ysolo, everyone.

[ Addendum 20161208: Ysolo has been canceled ]

[Other articles in category /wikipedia] permanent link

Fri, 11 Nov 2016

The worst literature reference ever

I think I may have found the single worst citation on Wikipedia. It's in the article on sausage casing. There is the following very interesting claim:

Reference to a cooked meat product stuffed in a goat stomach like a sausage was known in Babylon and described as a recipe in the world’s oldest cookbook 3,750 years ago.

That was exciting, and I wanted to know more. And there was a citation, so I could follow up!

The citation was:

(Yale Babylonian collection, New Haven Connecticut, USA)

I had my work cut out for me. All I had to do was drive up to New Haven and start translating their 45,000 cuneiform tablets until I found the cookbook.

(I tried to find a better reference, and turned up the book The Oldest Cuisine in the World: Cooking in Mesopotamia. The author, Jean Bottéro, was the discoverer of the cookbook, or rather he was the person who recognized that this tablet was a cookbook and not a pharmacopoeia or whatever. If the Babylonian haggis recipe is anywhere, it is probably there.)

[ Addendum 20230516: Renan Gross has brought to my attention that the Yale tablets are now available online, so it is no longer necessary to go all the way to New Haven. There are several tablets of cluinary recipes. ]

[Other articles in category /wikipedia] permanent link

Fri, 29 Jul 2016

Decomposing a function into its even and odd parts

As I have mentioned before, I am not a sudden-flash-of-insight person. Every once in a while it happens, but usually my thinking style is to minutely examine a large mass of examples and then gradually synthesize some conclusion about them. I am a penetrating but slow thinker. But there have been a few occasions in my life when the solution to a problem struck me suddenly out of the blue.

One such occasion was on the first day of my sophomore honors physics class in 1987. This was one of the best classes I took in my college career. It was given by Professor Stephen Nettel, and it was about resonance phenomena. I love when a course has a single overarching theme and proceeds to examine it in detail; that is all too rare. I deeply regret leaving my copy of the course notes in a restaurant in 1995.

The course was very difficult, But also very satisfying. It was also somewhat hair-raising, because of Professor Nettel's habit of saying, all through the second half “Don't worry if it doesn't seem to make any sense, it will all come together for you during the final exam.” This was not reassuring. But he was right! It did all come together during the final exam.

The exam had two sets of problems. The problems on the left side of the exam paper concerned some mechanical system, I think a rod fixed at one end and free at the other, or something like that. This set of problems asked us to calculate the resonant frequency of the rod, its rate of damping at various driving frequencies, and related matters. The right-hand problems were about an electrical system involving a resistor, capacitor, and inductor. The questions were the same, and the answers were formally identical, differing only in the details: on the left, the answers involved length, mass and stiffness of the rod, and on the right, the resistance, capacitance, and inductance of the electrical components. It was a brilliant exam, and I have never learned so much about a subject during the final exam.

Anyway, I digress. After the first class, we were assigned homework. One of the problems was

Show that every function is the sum of an even function and an odd function.

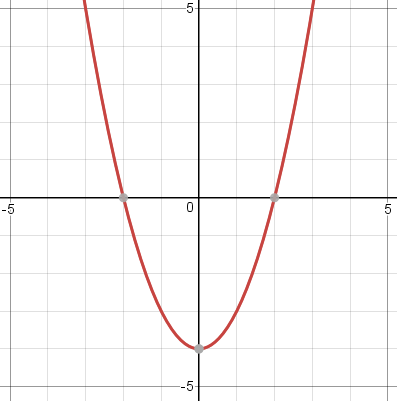

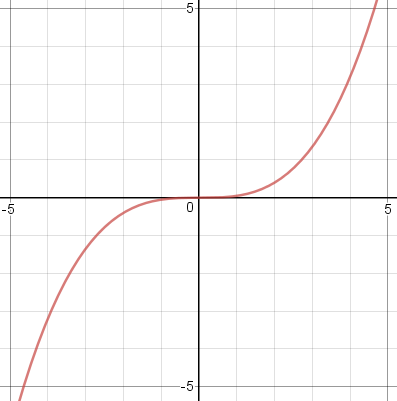

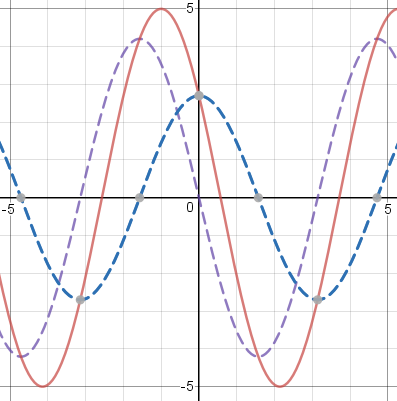

(Maybe I should explain that an even function is one which is symmetric across the !!y!!-axis; formally it is a function !!f!! for which !!f(x) = f(-x)!! for every !!x!!. For example, the function !!x^2-4!!, shown below left. An odd function is one which is symmetric under a half-turn about the origin; formally it satisfies !!f(x) = -f(-x)!! for all !!x!!. For example !!\frac{x^3}{20}!!, shown below right.)

I found this claim very surprising, and we had no idea how to solve it. Well, not quite no idea: I knew that functions could be expanded in Fourier series, as the sum of a sine series and a cosine series, and the sine part was odd while the cosine part was even. But this seemed like a bigger hammer than was required, particularly since new sophomores were not expected to know about Fourier series.

I had the privilege to be in that class with Ron Buckmire, and I remember we stood outside the class building in the autumn sunshine and discussed the problem. I might have been thinking that perhaps there was some way to replace the negative part of !!f!! with a reflected copy of the positive part to make an even function, and maybe that !!f(x) + f(-x)!! was always even, when I was hit from the blue with the solution:

$$ \begin{align} f_e(x) & = \frac{f(x) + f(-x)}2 \text{ is even},\\ f_o(x) & = \frac{f(x) - f(-x)}2 \text{ is odd, and}\\ f(x) &= f_e(x) + f_o(x) \end{align} $$

So that was that problem solved. I don't remember the other three problems in that day's homework, but I have remembered that one ever since.

But for some reason, it didn't occur to me until today to think about what those functions actually looked like. Of course, if !!f!! itself is even, then !!f_e = f!! and !!f_o = 0!!, and similarly if !!f!! is odd. But most functions are neither even nor odd.

For example, consider the function !!2^x!!, which is neither even nor odd. Then we get

$$ \begin{align} f_e(x) & = \frac{2^x + 2^{-x}}2\\ f_o(x) & = \frac{2^x - 2^{-x}}2 \end{align} $$

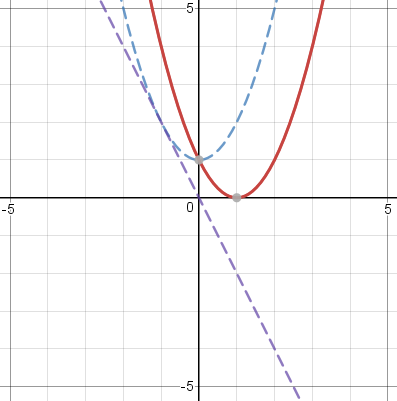

The graph is below left. The solid red line is !!2^x!!, and the blue and purple dotted lines are !!f_e!! and !!f_o!!. The red line is the sum of the blue and purple lines. I thought this was very interesting-looking, but a little later I realized that I had already known what these graphs would look like, because !!2^x!! is just like !!e^x!!, and for !!e^x!! the even and odd components are exactly the familiar !!\cosh!! and !!\sinh!! functions. (Below left, !!2^x!!; below right, !!e^x!!.)

I wasn't expecting polynomials to be more interesting, but they were. (Polynomials whose terms are all odd powers of !!x!!, such as !!x^{13} - 4x^5 + x!!, are always odd functions, and similarly polynomials whose terms are all even powers of !!x!! are even functions.) For example, consider !!(x-1)^2!!, which is neither even nor odd. We don't even need the !!f_e!! and !!f_o!! formulas to separate this into even and odd parts: just expand !!(x-1)^2!! as !!x^2 - 2x + 1!! and separate it into odd and even powers, !!-2x!! and !!x^2 + 1!!:

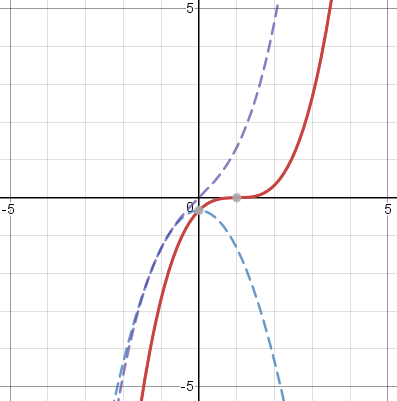

Or we could do !!\frac{(x-1)^3}3!! similarly, expanding it as !!\frac{x^3}3 - x^2 + x -\frac13!! and separating this into !!-x^2 -\frac13!! and !!\frac{x^3}3 + x!!:

I love looking at these and seeing how the even blue line and the odd purple line conspire together to make whatever red line I want.

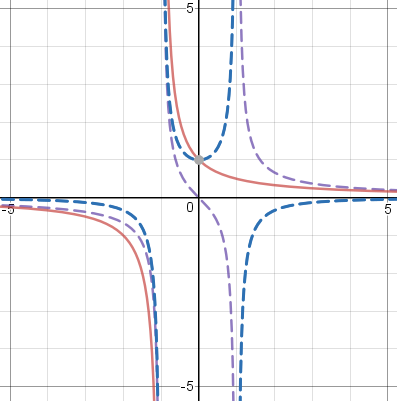

I kept wanting to try familiar simple functions, like !!\frac1x!!, but many of these are either even or odd, and so are uninteresting for this application. But you can make an even or an odd function into a neither-even-nor-odd function just by translating it horizontally, which you do by replacing !!x!! with !!x-c!!. So the next function I tried was !!\frac1{x+1}!!, which is the translation of !!\frac 1x!!. Here I got a surprise. I knew that !!\frac1{x+1}!! was undefined at !!x=-1!!, so I graphed it only for !!x>-1!!. But the even component is !!\frac12\left(\frac1{1+x}+\frac1{1-x}\right)!!, which is undefined at both !!x=-1!! and at !!x=+1!!. Similarly the odd component is undefined at two points. So the !!f = f_o + f_e!! formula does not work quite correctly, failing to produce the correct value at !!x=1!!, even though !!f!! is defined there. In general, if !!f!! is undefined at some !!x=c!!, then the decomposition into even and odd components fails at !!x=-c!! as well. The limit $$\lim_{x\to -c} f(x) = \lim_{x\to -c} \left(f_o(x) + f_e(x)\right)$$ does hold, however. The graph below shows the decomposition of !!\frac1{x+1}!!.

Vertical translations are uninteresting: they leave !!f_o!! unchanged and translate !!f_e!! by the same amount, as you can verify algebraically or just by thinking about it.

Following the same strategy I tried a cosine wave. The evenness of the cosine function is one of its principal properties, so I translated it and used !!\cos (x+1)!!. The graph below is actually for !!5\cos(x+1)!! to prevent the details from being too compressed:

This reminded me of the time I was fourteen and graphed !!\sin x + \cos x!! and was surprised to see that it was another perfect sinusoid. But I realized that there was a simple way to understand this. I already knew that !!\cos(x + y) = \sin x\cos y + \sin y \cos x!!. If you take !!y=\frac\pi4!! and multiply the whole thing by !!\sqrt 2!!, you get $$\sqrt2\cos\left(x + \frac\pi4\right) = \sqrt2\sin x\cos\frac\pi4 + \sqrt2\cos x\sin\frac\pi4 = \sin x + \cos x$$ so that !!\sin x + \cos x!! is just a shifted, scaled cosine curve. The decomposition of !!\cos(x+1)!! is even simpler because you can work forward instead of backward and find that !!\cos(x+1) = \sin x\cos 1 + \cos x \sin 1!!, and the first term is odd while the second term is even, so that !!\cos(x+1)!! decomposes as a sum of an even and an odd sinusoid as you see in the graph above.

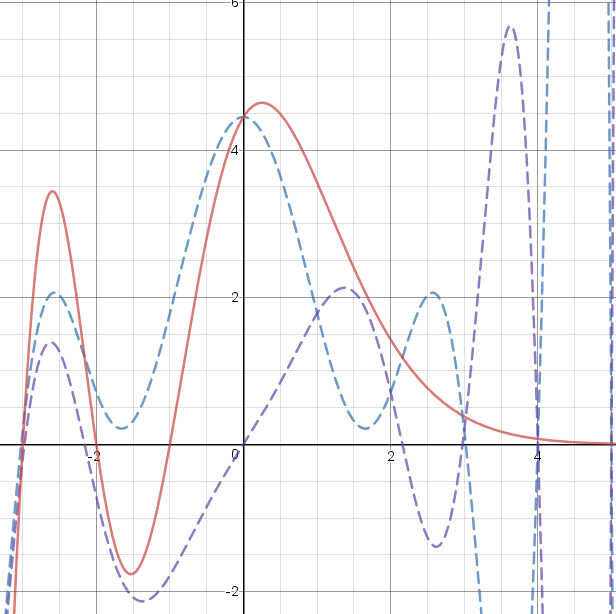

Finally, I tried a Poisson distribution, which is highly asymmetric. The formula for the Poisson distribution is !!\frac{\lambda^xe^\lambda}{x!}!!, for some constant !!\lambda!!. The !!x! !! in the denominator is only defined for non-negative integer !!x!!, but you can extend it to fractional and negative !!x!! in the usual way by using !!\Gamma(x+1)!! instead, where !!\Gamma!! is the Gamma function. The !!\Gamma!! function is undefined at zero and negative integers, but fortunately what we need here is the reciprocal gamma function !!\frac1{\Gamma(x)}!!, which is perfectly well-behaved. The results are spectacular. The graph below has !!\lambda = 0.8!!.

The part of this with !!x\ge 0!! is the most interesting to me, because the Poisson distribution has a very distinctive shape, and once again I like seeing the blue and purple !!\Gamma!! functions working together to make it. I think it's just great how the red line goes gently to zero as !!x!! increases, even though the even and the odd components are going wild. (!!x! !! increases rapidly with !!x!!, so the reciprocal !!\Gamma!! function goes rapidly to zero. But the even and odd components also have a !!\frac1{\Gamma(-x)}!! part, and this is what dominates the blue and purple lines when !!x >4!!.)

On the !!x\lt 0!! side it has no meaning for me, and it's just wiggly lines. It hadn't occurred to me before that you could extend the Poisson distribution function to negative !!x!!, and I still can't imagine what it could mean, but I suppose why not. Probably some statistician could explain to me what the Poisson distribution is about when !!x<0!!.

You can also consider the function !!\sqrt x!!, which breaks down completely, because either !!\sqrt x!! or !!\sqrt{-x}!! is undefined except when !!x=0!!. So the claim that every function is the sum of an even and an odd function fails here too. Except perhaps not! You could probably consider the extension of the square root function to the complex plane, and take one of its branches, and I suppose it works out just fine. The geometric interpretation of evenness and oddness are very different, of course, and you can't really draw the graphs unless you have four-dimensional vision.

I have no particular point to make, except maybe that math is fun, even elementary math (or perhaps especially elementary math) and it's fun to see how it works out.

The beautiful graphs in this article were made with Desmos. I had dreaded having to illustrate my article with graphs from Gnuplot (ugh) or Wolfram|α (double ugh) and was thrilled to find such a handsome alternative.

[ Addendum: I've just discovered that in Desmos you can include a parameter in the functions that it graphs, and attach the parameter to a slider. So for example you can arrange to have it display !!(x+k)^3!! or !!e^{-(x+k)^2}!!, with the value of !!k!! controlled by the slider, and have the graph move left and right on the plane as you adjust the slider, with its even and odd parts changing in real time to match. ]

[ For example, check out travelling Gaussians or varying sinusoid. ]

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link

Thu, 28 Jul 2016

Controlling the KDE screen locking works now

Yesterday I wrote about how I was trying to control the KDE screenlocker's timeout from a shell script and all the fun stuff I learned along the way. Then after I published the article I discovered that my solution didn't work. But today I fixed it and it does work.

What didn't work

I had written this script:

timeout=${1:-3600}

perl -i -lpe 's/^Enabled=.*/Enabled=False/' $HOME/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /MainApplication reparseConfiguration

sleep $timeout

perl -i -lpe 's/^Enabled=.*/Enabled=True/' $HOME/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /MainApplication reparseConfiguration

The strategy was: use perl to rewrite the screen locker's

configuration file, and then use qdbus to send a D-Bus message to

the screen locker to order it to load the updated configuration.

This didn't work. The System Settings app would see the changed

configuration, and report what I expected, but the screen saver itself

was still behaving according to the old configuration. Maybe the

qdbus command was wrong or maybe the whole theory was bad.

More strace

For want of anything else to do (when all you have is a hammer…), I

went back to using strace to see what else I could dig up, and tried

strace -ff -o /tmp/ss/s /usr/bin/systemsettings

which tells strace to write separate files for each process or

thread.

I had a fantasy that by splitting the trace for each process into a

separate file, I might solve the mysterious problem of the missing

string data. This didn't come true, unfortunately.

I then ran tail -f on each of the output files, and used

systemsettings to update the screen locker configuration, looking to

see which the of the trace files changed. I didn't get too much out

of this. A great deal of the trace was concerned with X protocol

traffic between the application and the display server. But I did

notice this portion, which I found extremely suggestive, even with the

filenames missing:

3106 open(0x2bb57a8, O_RDWR|O_CREAT|O_CLOEXEC, 0666) = 18

3106 fcntl(18, F_SETFD, FD_CLOEXEC) = 0

3106 chmod(0x2bb57a8, 0600) = 0

3106 fstat(18, {...}) = 0

3106 write(18, 0x2bb5838, 178) = 178

3106 fstat(18, {...}) = 0

3106 close(18) = 0

3106 rename(0x2bb5578, 0x2bb4e48) = 0

3106 unlink(0x2b82848) = 0

You may recall that my theory was that when I click the “Apply” button

in System Settings, it writes out a new version of

$HOME/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc and then orders the screen

locker to reload the configuration. Even with no filenames, this part

of the trace looked to me like the replacement of the configuration

file: a new file is created, then written, then closed, and then the

rename replaces the old file with the new one. If I had been

thinking about it a little harder, I might have thought to check if

the return value of the write call, 178 bytes, matched the length of

the file. (It does.) The unlink at the end is deleting the

semaphore file that System Settings created to prevent a second

process from trying to update the same file at the same time.

Supposing that this was the trace of the configuration update, the next section should be the secret sauce that tells the screen locker to look at the new configuration file. It looked like this:

3106 sendmsg(5, 0x7ffcf37e53b0, MSG_NOSIGNAL) = 168

3106 poll([?] 0x7ffcf37e5490, 1, 25000) = 1

3106 recvmsg(5, 0x7ffcf37e5390, MSG_CMSG_CLOEXEC) = 90

3106 recvmsg(5, 0x7ffcf37e5390, MSG_CMSG_CLOEXEC) = -1 EAGAIN (Resource temporarily unavailable)

3106 sendmsg(5, 0x7ffcf37e5770, MSG_NOSIGNAL) = 278

3106 sendmsg(5, 0x7ffcf37e5740, MSG_NOSIGNAL) = 128

There is very little to go on here, but none of it is inconsistent with the theory that this is the secret sauce, or even with the more advanced theory that it is the secret suace and that the secret sauce is a D-Bus request. But without seeing the contents of the messages, I seemed to be at a dead end.

Thrashing

Browsing random pages about the KDE screen locker, I learned that the lock screen configuration component could be run separately from the rest of System Settings. You use

kcmshell4 --list

to get a list of available components, and then

kcmshell4 screensaver

to run the screensaver component. I started running strace on this

command instead of on the entire System Settings app, with the idea

that if nothing else, the trace would be smaller and perhaps simpler,

and for some reason the missing strings appeared. That suggestive

block of code above turned out to be updating the configuration file, just

as I had suspected:

open("/home/mjd/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrcQ13893.new", O_RDWR|O_CREAT|O_CLOEXEC, 0666) = 19

fcntl(19, F_SETFD, FD_CLOEXEC) = 0

chmod("/home/mjd/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrcQ13893.new", 0600) = 0

fstat(19, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0600, st_size=0, ...}) = 0

write(19, "[ScreenSaver]\nActionBottomLeft=0\nActionBottomRight=0\nActionTopLeft=0\nActionTopRight=2\nEnabled=true\nLegacySaverEnabled=false\nPlasmaEnabled=false\nSaver=krandom.desktop\nTimeout=60\n", 177) = 177

fstat(19, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0600, st_size=177, ...}) = 0

close(19) = 0

rename("/home/mjd/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrcQ13893.new", "/home/mjd/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc") = 0

unlink("/home/mjd/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc.lock") = 0

And the following secret sauce was revealed as:

sendmsg(7, {msg_name(0)=NULL, msg_iov(2)=[{"l\1\0\1\30\0\0\0\v\0\0\0\177\0\0\0\1\1o\0\25\0\0\0/org/freedesktop/DBus\0\0\0\6\1s\0\24\0\0\0org.freedesktop.DBus\0\0\0\0\2\1s\0\24\0\0\0org.freedesktop.DBus\0\0\0\0\3\1s\0\f\0\0\0GetNameOwner\0\0\0\0\10\1g\0\1s\0\0", 144}, {"\23\0\0\0org.kde.screensaver\0", 24}], msg_controllen=0, msg_flags=0}, MSG_NOSIGNAL) = 168

sendmsg(7, {msg_name(0)=NULL, msg_iov(2)=[{"l\1\1\1\206\0\0\0\f\0\0\0\177\0\0\0\1\1o\0\25\0\0\0/org/freedesktop/DBus\0\0\0\6\1s\0\24\0\0\0org.freedesktop.DBus\0\0\0\0\2\1s\0\24\0\0\0org.freedesktop.DBus\0\0\0\0\3\1s\0\10\0\0\0AddMatch\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\10\1g\0\1s\0\0", 144}, {"\201\0\0\0type='signal',sender='org.freedesktop.DBus',interface='org.freedesktop.DBus',member='NameOwnerChanged',arg0='org.kde.screensaver'\0", 134}], msg_controllen=0, msg_flags=0}, MSG_NOSIGNAL) = 278

sendmsg(7, {msg_name(0)=NULL, msg_iov(2)=[{"l\1\0\1\0\0\0\0\r\0\0\0j\0\0\0\1\1o\0\f\0\0\0/ScreenSaver\0\0\0\0\6\1s\0\23\0\0\0org.kde.screensaver\0\0\0\0\0\2\1s\0\23\0\0\0org.kde.screensaver\0\0\0\0\0\3\1s\0\t\0\0\0configure\0\0\0\0\0\0\0", 128}, {"", 0}], msg_controllen=0, msg_flags=0}, MSG_NOSIGNAL) = 128

sendmsg(7, {msg_name(0)=NULL,

msg_iov(2)=[{"l\1\1\1\206\0\0\0\16\0\0\0\177\0\0\0\1\1o\0\25\0\0\0/org/freedesktop/DBus\0\0\0\6\1s\0\24\0\0\0org.freedesktop.DBus\0\0\0\0\2\1s\0\24\0\0\0org.freedesktop.DBus\0\0\0\0\3\1s\0\v\0\0\0RemoveMatch\0\0\0\0\0\10\1g\0\1s\0\0",

144},

{"\201\0\0\0type='signal',sender='org.freedesktop.DBus',interface='org.freedesktop.DBus',member='NameOwnerChanged',arg0='org.kde.screensaver'\0",

134}]

(I had to tell give strace the -s 256 flag to tell it not to

truncate the string data to 32 characters.)

Binary gibberish

A lot of this is illegible, but it is clear, from the frequent

mentions of DBus, and from the names of D-Bus objects and methods,

that this is is D-Bus requests, as theorized. Much of it is binary

gibberish that we can only read if we understand the D-Bus line

protocol, but the object and method names are visible. For example,

consider this long string:

interface='org.freedesktop.DBus',member='NameOwnerChanged',arg0='org.kde.screensaver'

With qdbus I could confirm that there was a service named

org.freedesktop.DBus with an object named / that supported a

NameOwnerChanged method which expected three QString arguments.

Presumably the first of these was org.kde.screensaver and the others

are hiding in other the 134 characters that strace didn't expand.

So I may not understand the whole thing, but I could see that I was on

the right track.

That third line was the key:

sendmsg(7, {msg_name(0)=NULL,

msg_iov(2)=[{"… /ScreenSaver … org.kde.screensaver … org.kde.screensaver … configure …", 128}, {"", 0}],

msg_controllen=0,

msg_flags=0},

MSG_NOSIGNAL) = 128

Huh, it seems to be asking the screensaver to configure itself. Just

like I thought it should. But there was no configure method, so what

does that configure refer to, and how can I do the same thing?

But org.kde.screensaver was not quite the same path I had been using

to talk to the screen locker—I had been using

org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver, so I had qdbus list the methods at

this new path, and there was a configure method.

When I tested

qdbus org.kde.screensaver /ScreenSaver configure

I found that this made the screen locker take note of the updated configuration. So, problem solved!

(As far as I can tell, org.kde.screensaver and

org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver are completely identical. They each

have a configure method, but I had overlooked it—several times in a

row—earlier when I had gone over the method catalog for

org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver.)

The working script is almost identical to what I had yesterday:

timeout=${1:-3600}

perl -i -lpe 's/^Enabled=.*/Enabled=False/' $HOME/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /ScreenSaver configure

sleep $timeout

perl -i -lpe 's/^Enabled=.*/Enabled=True/' $HOME/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /ScreenSaver configure

That's not a bad way to fail, as failures go: I had a correct idea

about what was going on, my plan about how to solve my problem would

have worked, but I was tripped up by a trivium; I was calling

MainApplication.reparseConfiguration when I should have been calling

ScreenSaver.configure.

What if I hadn't been able to get strace to disgorge the internals

of the D-Bus messages? I think I would have gotten the answer anyway.

One way to have gotten there would have been to notice the configure

method documented in the method catalog printed out by qdbus. I

certainly looked at these catalogs enough times, and they are not very

large. I don't know why I never noticed it on my own. But I might

also have had the idea of spying on the network traffic through the

D-Bus socket, which is under /tmp somewhere.

I was also starting to tinker with dbus-send, which is like qdbus

but more powerful, and can post signals, which I think qdbus can't

do, and with gdbus, another D-Bus introspector. I would have kept

getting more familiar with these tools and this would have led

somewhere useful.

Or had I taken just a little longer to solve this, I would have

followed up on Sumana Harihareswara’s suggestion to look at

Bustle, which is

a utility that logs and traces D-Bus requests. It would certainly

have solved my problem, because it makes perfectly clear that clicking

that apply button invoked the configure method:

I still wish I knew why strace hadn't been able to print out those

strings through.

[Other articles in category /Unix] permanent link

Wed, 27 Jul 2016

Controlling KDE screen locking from a shell script

Lately I've started watching stuff on Netflix. Every time I do this, the screen locker kicks in sixty seconds in, and I have to unlock it, pause the video, and adjust the system settings to turn off the automatic screen locker. I can live with this.

But when the show is over, I often forget to re-enable the automatic screen locker, and that I can't live with. So I wanted to write a shell script:

#!/bin/sh

auto-screen-locker disable

sleep 3600

auto-screen-locker enable

Then I'll run the script in the background before I start watching, or at least after the first time I unlock the screen, and if I forget to re-enable the automatic locker, the script will do it for me.

The question is: how to write auto-screen-locker?

strace

My first idea was: maybe there is actually an auto-screen-locker

command, or a system-settings command, or something like that, which

was being run by the System Settings app when I adjusted the screen

locker from System Settings, and all I needed to do was to find out

what that command was and to run it myself.

So I tried running System Settings under strace -f and then looking

at the trace to see if it was execing anything suggestive.

It wasn't, and the trace was 93,000 lines long and frighting. Halfway

through, it stopped recording filenames and started recording their

string addresses instead, which meant I could see a lot of calls to

execve but not what was being execed. I got sidetracked trying to

understand why this had happened, and I never did figure it

out—something to do with a call to clone, which is like fork, but

different in a way I might understand once I read the man page.

The first thing the cloned process did was to call set_robust_list,

which I had never heard of, and when I looked for its man page I found

to my surprise that there was one. It begins:

NAME

get_robust_list, set_robust_list - get/set list of robust futexes

And then I felt like an ass because, of course, everyone knows all about the robust futex list, duh, how silly of me to have forgotten ha ha just kidding WTF is a futex? Are the robust kind better than regular wimpy futexes?

It turns out that Ingo Molnár wrote a lovely explanation of robust futexes which are actually very interesting. In all seriousness, do check it out.

I seem to have digressed. This whole section can be summarized in one sentence:

stracewas no help and took me a long way down a wacky rabbit hole.

Sorry, Julia!

Stack Exchange

The next thing I tried was Google search for kde screen locker. The

second or third link I followed was to this StackExchange question,

“What is the screen locking mechanism under

KDE?

It wasn't exactly what I was looking for but it was suggestive and

pointed me in the right direction. The crucial point in the answer

was a mention of

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /ScreenSaver Lock

When I saw this, it was like a new section of my brain coming on line. So many things that had been obscure suddenly became clear. Things I had wondered for years. Things like “What are these horrible

Object::connect: No such signal org::freedesktop::UPower::DeviceAdded(QDBusObjectPath)

messages that KDE apps are always spewing into my terminal?” But now the light was on.

KDE is built atop a toolkit called Qt, and Qt provides an interprocess

communication mechanism called “D-Bus”. The qdbus command, which I

had not seen before, is apparently for sending queries and commands on

the D-Bus. The arguments identify the recipient and the message you

are sending. If you know the secret name of the correct demon, and

you send it the correct secret command, it will do your bidding. (

The mystery message above probably has something to do with the app

using an invalid secret name as a D-Bus address.)

Often these sorts of address hierarchies work well in theory and then

fail utterly because there is no way to learn the secret names. The X

Window System has always had a feature called “resources” by which

almost every aspect of every application can be individually

customized. If you are running xweasel and want just the frame of

just the error panel of just the output window to be teal blue, you

can do that… if you can find out the secret names of the xweasel

program, its output window, its error panel, and its frame. Then you

combine these into a secret X resource name, incant a certain command

to load the new resource setting into the X server, and the next time

you run xweasel the one frame, and only the one frame, will be blue.

In theory these secret names are documented somewhere, maybe. In

practice, they are not documented anywhere. you can only extract them

from the source, and not only from the source of xweasel itself but

from the source of the entire widget toolkit that xweasel is linked

with. Good luck, sucker.

D-Bus has a directory

However! The authors of Qt did not forget to include a directory mechanism in D-Bus. If you run

qdbus

you get a list of all the addressable services, which you can grep for

suggestive items, including org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver. Then if

you run

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver

you get a list of all the objects provided by the

org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver service; there are only seven. So you

pick a likely-seeming one, say /ScreenSaver, and run

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /ScreenSaver

and get a list of all the methods that can be called on this object, and their argument types and return value types. And you see for example

method void org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver.Lock()

and say “I wonder if that will lock the screen when I invoke it?” And then you try it:

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /ScreenSaver Lock

and it does.

That was the most important thing I learned today, that I can go

wandering around in the qdbus hierarchy looking for treasure. I

don't yet know exactly what I'll find, but I bet there's a lot of good stuff.

When I was first learning Unix I used to wander around in the filesystem looking at all the files, and I learned a lot that way also.

“Hey, look at all the stuff in

/etc! Huh, I wonder what's in/etc/passwd?”“Hey,

/etc/protocolshas a catalog of protocol numbers. I wonder what that's for?”“Hey, there are a bunch of files in

/usr/spool/mailnamed after users and the one with my name has my mail in it!”“Hey, the manuals are all under

/usr/man. I could grep them!”

Later I learned (by browsing in /usr/man/man7) that there was a

hier(7) man page that listed points of interest, including some I

had overlooked.

The right secret names

Everything after this point was pure fun of the “what happens if I

turn this knob” variety. I tinkered around with the /ScreenSaver

methods a bit (there are twenty) but none of them seemed to be quite

what I wanted. There is a

method uint Inhibit(QString application_name, QString reason_for_inhibit)

method which someone should be calling, because that's evidently what you call if you are a program playing a video and you want to inhibit the screen locker. But the unknown someone was delinquent and it wasn't what I needed for this problem.

Then I moved on to the /MainApplication object and found

method void org.kde.KApplication.reparseConfiguration()

which wasn't quite what I was looking for either, but it might do: I

could perhaps modify the configuration and then invoke this method. I

dimly remembered that KDE keeps configuration files under

$HOME/.kde, so I ls -la-ed that and quickly found

share/config/kscreensaverrc, which looked plausible from the

outside, and more plausible when I saw what was in it:

Enabled=True

Timeout=60

among other things. I hand-edited the file to change the 60 to

243, ran

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /MainApplication reparseConfiguration

and then opened up the System Settings app. Sure enough, the System

Settings app now reported that the lock timeout setting was “4

minutes”. And changing Enabled=True to Enabled=False and back

made the System Settings app report that the locker was enabled or

disabled.

The answer

So the script I wanted turned out to be:

timeout=${1:-3600}

perl -i -lpe 's/^Enabled=.*/Enabled=False/' $HOME/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /MainApplication reparseConfiguration

sleep $timeout

perl -i -lpe 's/^Enabled=.*/Enabled=True/' $HOME/.kde/share/config/kscreensaverrc

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /MainApplication reparseConfiguration

Problem solved, but as so often happens, the journey was more important than the destination.

I am greatly looking forward to exploring the D-Bus hierarchy and sending all sorts of inappropriate messages to the wrong objects.

Just before he gets his ass kicked by Saruman, that insufferable know-it-all Gandalf says “He who breaks a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom.” If I had been Saruman, I would have kicked his ass at that point too.

Addendum

Right after I posted this, I started watching Netflix. The screen locker cut in after sixty seconds. “Aha!” I said. “I'll run my new script!”

I did, and went back to watching. Sixty seconds later, the screen

locker cut in again. My script doesn't work! The System Settings app

says the locker has been disabled, but it's mistaken. Probably it's only

reporting the contents of the configuration file that I edited, and

the secret sauce is still missing. The System Settings app does

something to update the state of the locker when I click that “Apply”

button, and I thought that my qdbus command was doing the same

thing, but it seems that it isn't.

I'll figure this out, but maybe not today. Good night all!

[ Addendum 20160728: I figured it out the next day ]

[ Addendum 20160729: It has come to my attention that there is

actually a program called xweasel. ]

[Other articles in category /Unix] permanent link

Thu, 21 Jul 2016

A hack for getting the email address Git will use for a commit

Today I invented a pretty good hack.

Suppose I have branch topic checked out. It often happens that I want to

git push origin topic:mjd/topic

which pushes the topic branch to the origin repository, but on

origin it is named mjd/topic instead of topic. This is a good

practice when many people share the same repository. I wanted to write

a program that would do this automatically.

So the question arose, how should the program figure out the mjd

part? Almost any answer would be good here: use some selection of

environment variables, the current username, a hard-wired default, and

the local part of Git's user.email configuration setting, in some

order. Getting user.email is easy (git config get user.email) but

it might not be set and then you get nothing. If you make a commit

but have no user.email, Git doesn't mind. It invents an address

somehow. I decided that I would like my program to to do exactly what

Git does when it makes a commit.

But what does Git use for the committer's email address if there is

no user.email set? This turns out to be complicated. It consults

several environment variables in some order, as I suggested before.

(It is documented in

git-commit-tree if you

are interested.) I did not want to duplicate Git's complicated

procedure, because it might change, and because duplicating code is a

sin. But there seemed to be no way to get Git to disgorge this value,

short of actually making a commit and examining it.

So I wrote this command, which makes a commit and examines it:

git log -1 --format=%ce $(git-commit-tree HEAD^{tree} < /dev/null)

This is extremely weird, but aside from that it seems to have no concrete drawbacks. It is pure hack, but it is a hack that works flawlessly.

What is going on here? First, the $(…) part:

git-commit-tree HEAD^{tree} < /dev/null

The git-commit-tree command is what git-commit uses to actually

create a commit. It takes a tree object, reads a commit message from

standard input, writes a new commit object, and prints its SHA1 hash

on standard output. Unlike git-commit, it doesn't modify the index

(git-commit would use git-write-tree to turn the index into a tree

object) and it doesn't change any of the refs (git-commit would

update the HEAD ref to point to the new commit.) It just creates

the commit.

Here we could use any tree, but the tree of the HEAD commit is

convenient, and HEAD^{tree} is its name. We supply an empty commit

message from /dev/null.

Then the outer command runs:

git log -1 --format=%ce $(…)

The $(…) part is replaced by the SHA1 hash of the commit we just

created with git-commit-tree. The -1 flag to git-log gets the

log information for just this one commit, and the --format=%ce tells

git-log to print out just the committer's email address, whatever it

is.

This is fast—nearly instantaneous—and cheap. It doesn't change the state of the repository, except to write a new object, which typically takes up 125 bytes. The new commit object is not attached to any refs and so will be garbage collected in due course. You can do it in the middle of a rebase. You can do it in the middle of a merge. You can do it with a dirty index or a dirty working tree. It always works.

(Well, not quite. It will fail if run in an empty repository, because

there is no HEAD^{tree} yet. Probably there are some other

similarly obscure failure modes.)

I called the shortcut git-push program

git-pusho

but I dropped the email-address-finder into

git-get,

which is my storehouse of weird “How do I find out X” tricks.

I wish my best work of the day had been a little bit more significant, but I'll take what I can get.

[ Addendum: Twitter user @shachaf has reminded me that the right way to do this is

git var GIT_COMMITTER_IDENT

which prints out something like

Mark Jason Dominus (陶敏修) <mjd@plover.com> 1469102546 -0400

which you can then parse. @shachaf also points out that a Stack Overflow discussion of this very question contains a comment suggesting the same weird hack! ]

[Other articles in category /prog] permanent link

Thu, 14 Jul 2016

Surprising reasons to use a syntax-coloring editor

[ Danielle Sucher reminded me of this article I wrote in 1998, before I had a blog, and I thought I'd repatriate it here. It should be interesting as a historical artifact, if nothing else. Thanks Danielle! ]

I avoided syntax coloring for years, because it seemed like a pretty stupid idea, and when I tried it, I didn't see any benefit. But recently I gave it another try, with Ilya Zakharevich's `cperl-mode' for Emacs. I discovered that I liked it a lot, but for surprising reasons that I wasn't expecting.

I'm not trying to start an argument about whether syntax coloring is good or bad. I've heard those arguments already and they bore me to death. Also, I agree with most of the arguments about why syntax coloring is a bad idea. So I'm not trying to argue one way or the other; I'm just relating my experiences with syntax coloring. I used to be someone who didn't like it, but I changed my mind.

When people argue about whether syntax coloring is a good idea or not, they tend to pull out the same old arguments and dust them off. The reasons I found for using syntax coloring were new to me; I'd never seen anyone mention them before. So I thought maybe I'd post them here.

Syntax coloring is when the editor understands something about the

syntax of your program and displays different language constructs in

different fonts. For example, cperl-mode displays strings in

reddish brown, comments in a sort of brick color, declared variables

(in my) in gold, builtin function names (defined) in green,

subroutine names in blue, labels in teal, and keywords (like my and

foreach) in purple.

The first thing that I noticed about this was that it was easier to recognize what part of my program I was looking at, because each screenful of the program had its own color signature. I found that I was having an easier time remembering where I was or finding that parts I was looking for when I scrolled around in the file. I wasn't doing this consciously; I couldn't describe the color scheme any particular part of the program was, but having red, gold, and purple blotches all over made it easier to tell parts of the program apart.

The other surprise I got was that I was having more fun programming. I felt better about my programs, and at the end of the day, I felt better about the work I had done, just because I'd spent the day looking at a scoop of rainbow sherbet instead of black and white. It was just more cheerful to work with varicolored text than monochrome text. The reason I had never noticed this before was that the other coloring editors I used had ugly, drab color schemes. Ilya's scheme won here by using many different hues.

I haven't found many of the other benefits that people say they get from syntax coloring. For example, I can tell at a glance whether or not I failed to close a string properly—unless the editor has screwed up the syntax coloring, which it does often enough to ruin the benefit for me. And the coloring also slows down the editor. But the two benefits I've described more than outweigh the drawbacks for me. Syntax coloring isn't a huge win, but it's definitely a win.

If there's a lesson to learn from this, I guess it's that it can be valuable to revisit tools that you rejected, to see if you've changed your mind. Nothing anyone said about it was persuasive to me, but when I tried it I found that there were reasons to do it that nobody had mentioned. Of course, these reasons might not be compelling for anyone else.

Addenda 2016

Looking back on this from a distance of 18 years, I am struck by the following thoughts:

Syntax highlighting used to make the editor really slow. You had to make a real commitment to using it or not. I had forgotten about that. Another victory for Moore’s law!

Programmers used to argue about it. Apparently programmers will argue about anything, no matter how ridiculous. Well okay, this is not a new observation. Anyway, this argument is now finished. Whether people use it or not, they no longer find the need to argue about it. This is a nice example that sometimes these ridiculous arguments eventually go away.

I don't remember why I said that syntax highlighting “seemed like a pretty stupid idea”, but I suspect that I was thinking that the wrong things get highlighted. Highlighters usually highlight the language keywords, because they're easy to recognize. But this is like highlighting all the generic filler words in a natural language text. The words you want to see are exactly the opposite of what is typically highlighted.

Syntax highlighters should be highlighting the semantic content like expression boundaries, implied parentheses, boolean subexpressions, interpolated variables and other non-apparent semantic features. I think there is probably a lot of interesting work to be done here. Often you hear programmers say things like “Oh, I didn't see the that the trailing comma was actually a period.” That, in my opinion, is the kind of thing the syntax highlighter should call out. How often have you heard someone say “Oh, I didn't see that

whilethere”?I have been misspelling “arguments” as “argmuents” for at least 18 years.

[Other articles in category /prog] permanent link

Tue, 12 Jul 2016

A simple but difficult arithmetic puzzle

Lately my kids have been interested in puzzles of this type: You are given a sequence of four digits, say 1,2,3,4, and your job is to combine them with ordinary arithmetic operations (+, -, ×, and ÷) in any order to make a target number, typically 24. For example, with 1,2,3,4, you can go with $$((1+2)+3)×4 = 24$$ or with $$4×((2×3)×1) = 24.$$

We were stumped trying to make 6,6,5,2 total 24, so I hacked up a solver; then we felt a little foolish when we saw the solutions, because it is not that hard. But in the course of testing the solver, I found the most challenging puzzle of this type that I've ever seen. It is:

Given 6,6,5,2, make 17.

There are no underhanded tricks. For example, you may not concatenate 2 and 5 to make 25; you may not say !!6÷6=1!! and !!5+2=7!! and concatenate 1 and 7 to make !!17!!; you may not interpret the 17 as a base 12 numeral, etc.

I hope to write a longer article about solvers in the next week or so.

[ Addendum 20170305: The next week or so, ha ha. Anyway, here it is. ]

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link

Mon, 11 Jul 2016

Addenda to recent articles 201607

Here are some notes on posts from the last couple of months that I couldn't find better places for.

I wrote a long article about tracking down a system bug. At some point I determined that the problem was related to Perl, and asked Frew Schmidt for advice. He wrote up the details of his own investigation, which pick up where mine ended. Check it out. I 100% endorse his lament about

ltrace.There was a Hacker News discussion about that article. One participant asked a very pertinent question:

I read this, but seemed to skip over the part where he explains why this changed suddenly, when the behavior was documented?

What changed to make the perl become capable whereas previously it lacked the low port capability?

So far, we don't know! Frew told me recently that he thinks the

TMPDIR-losing has been going on for months and that whatever precipitated my problem is something else.In my article on the Greek clock, I guessed a method for calculating the (approximate) maximum length of the day from the latitude: $$ A = 360 \text{ min}\cdot(1-\cos L).$$

Sean Santos of UCAR points out that this is inaccurate close to the poles. For places like Philadelphia (40° latitude) it is pretty close, but it fails completely for locations north of the Arctic Circle. M. Santos advises instead:

$$ A = 360 \text{ min}\cdot \frac{2}{\pi}\cdot \sin^{-1}(\tan L\cdot \tan\epsilon)$$

where ε is the axial tilt of the Earth, approximately 23.4°. Observe that when !!L!! is above the Arctic Circle (or below the Antarctic) we have !!\tan L \cdot \tan \epsilon > 1!! (because !!\frac1{\tan x} = \tan(90^\circ - x)!!) so the arcsine is undefined, and we get no answer.

[Other articles in category /addenda] permanent link

Fri, 01 Jul 2016

Don't tug on that, you never know what it might be attached to

This is a story about a very interesting bug that I tracked down yesterday. It was causing a bad effect very far from where the bug actually was.

emacsclient

The emacs text editor comes with a separate utility, called

emacsclient, which can communicate with the main editor process and

tell it to open files for editing. You have your main emacs

running. Then somewhere else you run the command

emacsclient some-files...

and it sends the main emacs a message that you want to edit

some-files. Emacs gets the message and pops up new windows for editing

those files. When you're done editing some-files you tell Emacs, by

typing C-# or something, it

it communicates back to emacsclient that the editing is done, and

emacsclient exits.

This was more important in the olden days when Emacs was big and bloated and took a long time to start up. (They used to joke that “Emacs” was an abbreviation for “Eight Megs And Constantly Swapping”. Eight megs!) But even today it's still useful, say from shell scripts that need to run an editor.

Here's the reason I was running it. I have a very nice shell script,

called also, that does something like this:

- Interpret command-line arguments as patterns

- Find files matching those patterns

- Present a menu of the files

- Wait for me to select files of interest

- Run

emacsclienton the selected files

It is essentially a wrapper around

menupick,

a menu-picking utility I wrote which has seen use as a component of

several other tools.

I can type

also Wizard

in the shell and get a menu of the files related to the wizard, select the ones I actually want to edit, and they show up in Emacs. This is more convenient than using Emacs itself to find and open them. I use it many times a day.

Or rather, I did until this week, when it suddenly stopped working.

Everything ran fine until the execution of emacsclient, which would

fail, saying:

emacsclient: can't find socket; have you started the server?

(A socket is a facility that enables interprocess communication, in

this case between emacs and emacsclient.)

This message is familiar. It usually means that I have forgotten to

tell Emacs to start listening for emacsclient, by running M-x

server-start. (I should have Emacs do this when it starts up, but I

don't. Why not? I'm not sure.) So the first time it happened I went

to Emacs and ran M-x server-start. Emacs announced that it had

started the server, so I reran also. And the same thing happened.

emacsclient: can't find socket; have you started the server?

Finding the socket

So the first question is: why can't emacsclient find the socket?

And this resolves naturally into two subquestions: where is the

socket, and where is emacsclient looking?

The second one is easily answered; I ran strace emacsclient (hi

Julia!) and saw that the last interesting thing emacsclient did

before emitting the error message was

stat("/mnt/tmp/emacs2017/server", 0x7ffd90ec4d40) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

which means it's looking for the socket at /mnt/tmp/emacs2017/server

but didn't find it there.

The question of where Emacs actually put the socket file was a little

trickier. I did not run Emacs under strace because I felt sure that

the output would be voluminous and it would be tedious to grovel over

it.

I don't exactly remember now how I figured this out, but I think now

that I probably made an educated guess, something like: emacsclient

is looking in /mnt/tmp; this seems unusual. I would expect the

socket to be under /tmp. Maybe it is under /tmp? So I looked

under /tmp and there it was, in /tmp/emacs2017/server:

srwx------ 1 mjd mjd 0 Jun 27 11:43 /tmp/emacs2017/server

(The s at the beginning there means that the file is a “Unix-domain

socket”. A socket is an endpoint for interprocess communication. The

most familiar sort is a TCP socket, which has a TCP address, and which

enables communication over the internet. But since ancient times Unix

has also supported Unix-domain sockets, which enable communication

between two processes on the same machine. Instead of TCP addresses,

such sockets are addressed using paths in the filesystem, in this case

/tmp/emacs2017/server. When the server creates such a socket, it

appears in the filesystem as a special type of file, as here.)

I confirmed that this was the correct file by typing M-x

server-force-delete in Emacs; this immediately caused

/tmp/emacs2017/server to disappear. Similarly M-x server-start

made it reappear.

Why the disagreement?

Now the question is: Why is emacsclient looking for the socket under

/mnt/tmp when Emacs is putting it in /tmp? They used to

rendezvous properly; what has gone wrong? I recalled that there was

some environment variable for controlling where temporary files are

put, so I did

env | grep mnt

to see if anything relevant turned up. And sure enough there was:

TMPDIR=/mnt/tmp

When programs want to create tmporary files and directories, they normally do it in /tmp. But

if there is a TMPDIR setting, they use that directory instead. This

explained why emacsclient was looking for

/mnt/tmp/emacs2017/socket. And the explanation for why Emacs itself

was creating the socket in /tmp seemed clear: Emacs was failing to

honor the TMPDIR setting.

With this clear explanation in hand, I began to report the bug in

Emacs, using M-x report-emacs-bug. (The folks in the #emacs IRC

channel on Freenode suggested this. I had a bad

experience last time I tried

#emacs, and then people mocked me for even trying to get useful

information out of IRC. But this time it went pretty well.)

Emacs popped up a buffer with full version information and invited me to write down the steps to reproduce the problem. So I wrote down

% export TMPDIR=/mnt/tmp

% emacs

and as I did that I ran those commands in the shell.

Then I wrote

In Emacs:

M-x getenv TMPDIR

(emacs claims there is no such variable)

and I did that in Emacs also. But instead of claiming there was no

such variable, Emacs cheerfully informed me that the value of TMPDIR

was /mnt/tmp.

(There is an important lesson here! To submit a bug report, you find a minimal demonstration. But then you also try the minimal demonstration exactly as you reported it. Because of what just happened! Had I sent off that bug report, I would have wasted everyone else's time, and even worse, I would have looked like a fool.)

My minimal demonstration did not demonstrate. Something else was going on.

Why no TMPDIR?

This was a head-scratcher. All I could think of was that

emacsclient and Emacs were somehow getting different environments,

one with the TMPDIR setting and one without. Maybe I had run them

from different shells, and only one of the shells had the setting?

I got on a sidetrack at this point to find out why TMPDIR was set in

the first place; I didn't think I had set it. I looked for it in

/etc/profile, which is the default Bash startup instructions, but it

wasn't there. But I also noticed an /etc/profile.d which seemed

relevant. (I saw later that the /etc/profile contained instructions

to load everything under /etc/profile.d.) And when I grepped for

TMPDIR in the profile.d files, I found that it was being set by

/etc/profile.d/ziprecruiter_environment.sh, which the sysadmins had

installed. So that mystery at least was cleared up.