Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2025: | JFMAM |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 99 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 15 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Thu, 24 Apr 2025

How our toy octopuses got revenge on a Philadelphia traffic court judge

[ Content warning: possibly amusing, but silly and pointless ]

My wife Lorrie wrote this on 31 January 2013:

I got an e-mail from Husband titled, "The mills of Fenchurch grind slow, but they grind exceeding small." This silliness, which is off-the-charts silly, is going to require explanation.

Fenchurch is a small blue octopus made of polyester fiberfill. He was the first one I ever bought, starting our family's octopus craze, and I gave him to Husband in 1994. He is extremely shy and introverted. He hates conflict and attention. He's a sensitive and very artistic soul. His favorite food is crab cakes, followed closely by shrimp. (We have made up favorite foods, professions, hobbies, and a zillion scenarios for all of our stuffed animals.)

In our house it was well-established canon that Fenchurch's favorite food was crab cakes. I had even included him as an example in some of my conference talks:

my $fenchurch = Octopus->new({

arms => 8,

hearts => 3,

favorite_food => "crab cakes"

});

He has a ladylove named Junko whom he takes on buggy rides on fine days. When Husband is feeling very creative and vulnerable, he identifies with Fenchurch.

Anyway, one time Husband got a traffic ticket and this Traffic Court judge named Fortunato N. Perri was unbelievably mocking to him at his hearing. Good thing Husband has the thick skin of a native Manhattanite. … It was so awful that Husband and I remember bits of it more than a decade later.

I came before Fortunato N. Perri in, I think, 1996. I had been involved in a very low-speed collision with someone, and I was ticketed because the proof of insurance in my glove box was expired. Rather than paying the fine, I appeared in traffic court to plead not guilty.

It was clear that Perri was not happy with his job as a traffic court judge. He had to listen to hundreds of people making the same lame excuses day after day. “I didn't see the stop sign.” “The sun was in my eyes.” “I thought the U-turn was legal.” I can't blame Perri for growing tired of this. But I can blame him for the way he handled it, which was to mock and humiliate the people who came before him.

“Where are you from?”

“Ohio.”

“Do they have stop signs in Ohio?”

“Uh, yes.”

“Do you know what they look like?”

“Yes.”

“Do they look like the stop signs we have here?”

“Yes.”

“Then how come you didn't see the stop sign? You say you know what a stop sign looks like but then you didn't stop. I'm fining you $100. You're dismissed.”

He tried to hassle me also, but I kept my cool, and since I wasn't actually in violation of the law he couldn't do anything to me. He did try to ridicule my earring.

“What does that thing mean?”

“It doesn't mean anything, it's just an earring.”

“Is that what everyone is doing now?”

“I don't know what everyone is doing.”

“How long ago did you get it?”

“Thirteen years.”

“Huh. … Well, you did have insurance, so I'm dismissing your ticket. You can go.”

I'm still wearing that earring today, Fortunato. By the way, Fortunato, the law is supposed to be calm and impartial, showing favor to no one.

Fortunato didn't just mock and humiliate the unfortunate citizens who came before him. He also abused his own clerks. One of them was doing her job, stapling together court papers on the desk in front of the bench, and he harangued her for doing it too noisily. “God, you might as well bring in a hammer and nails and start hammering up here, bang bang bang!”

I once went back to traffic court just to observe, but he wasn't in that day. Instead I saw how a couple of other, less obnoxious judges ran things.

Lorrie continues:

Husband has been following news about this judge (now retired) and his family ever since, and periodically he gives me updates.

(His son, Fortunato N. Perri Jr., is a local civil litigation attorney of some prominence. As far as I know there is nothing wrong with Perri Jr.)

And we made up a story that Fenchurch was traumatized by this guy after being ticketed for parking in a No Buggy zone.

So today, he was charged with corruption after a three-year FBI probe. The FBI even raided his house

I understood everything when I read that Perri accepted graft in many forms, including shrimp and crab cakes.

OMG. No wonder my little blue octopus was wroth. No wonder he swore revenge. This crooked thief was interfering with his food supply!

Lorrie wrote a followup the next day:

I confess Husband and I spent about 15 minutes last night savoring details about Fortunato N. Perri's FBI bust. Apparently, even he had a twinge of conscience at the sheer quantity of SHRIMP and CRAB CAKES he got from this one strip club owner in return for fixing tickets. (Husband noted that he managed to get over his qualms.)

Husband said Perri hadn't been too mean to him, but Husband still feels bad about the way Perri screamed at his hapless courtroom assistant, who was innocently doing her job stapling papers until Perri stopped proceedings to holler that she was making so much noise, she may as well be using a hammer.

Fenchurch and his ladylove Junko, who specialize in avant garde performance art, greeted Husband last night with their newest creation, called "Schadenfreude." It mostly involved wild tentacle waving and uninhibited cackling. Then they declared it to be the best day of their entire lives and stayed up half the night partying.

Epilogues

Later that year, the notoriously corrupt Traffic Court was abolished, its functions transferred to regular Philadelphia Municipal Court.

In late 2014, four of Perri's Traffic Court colleagues were convicted of federal crimes. They received prison sentences of 18 to 20 months.

Fortunato Perri himself, by then 78 years old and in poor health, pled guilty, and was sentenced to two years of probation.

The folks who supplied the traffic tickets and the seafood bribes were also charged. They tried to argue that they hadn't defrauded the City of Philadelphia because the people they paid Perri to let off the hook hadn't been found guilty, and would only have owed fines if they had been found guilty.

The judges in their appeal were not impressed with this argument. See United States v. Hird et al..

One of those traffic court judges was Willie Singletary, who I've been planning to write about since 2019. But he is a hard worker who deserves better than to be stuck in an epilogue, so I'll try to get to him later this month.

(Update 20250426: Willie Singletary, ladies and gentlemen!)

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Wed, 31 May 2023

More about _Cozzi v. Village of Melrose Park_

Earlier today I brought up the case of Cozzi v. Village of Melrose Park and the restrained but unmistakably threatening tone of the opening words of the judge's opinion in that case:

The Village of Melrose Park decided that it would be a good idea

I didn't want to distract from the main question, so I have put the details in this post instead. the case is Cozzi v. Village of Melrose Park N.D.Ill. 21-cv-998, and the judge's full opening paragraph is:

The Village of Melrose Park decided that it would be a good idea to issue 62 tickets to an elderly couple for having lawn chairs in their front yard. The Village issued ticket after ticket, imposing fine after fine, to two eighty-year-old residents, Plaintiffs Vincent and Angeline Cozzi.

The full docket is available on CourtListener. Mr. Cozzi died in February 2022, sometime before the menacing opinion was written, and the two parties are scheduled to meet for settlement talks next Thursday, June 8.

The docket also contains the following interesting entry from the judge:

On December 1, 2021, George Becker, an attorney for third-party deponent Brandon Theodore, wrote a letter asking to reschedule the deposition, which was then-set for December 2. He explained that a "close family member who lives in my household has tested positive for Covid-19." He noted that he "need[ed] to reschedule it" because "you desire this deposition live," which the Court understands to mean in-person testimony. That cancellation made perfect sense. We're in a pandemic, after all. Protecting the health and safety of everyone else is a thoughtful thing to do. One might have guessed that the other attorneys would have appreciated the courtesy. Presumably Plaintiff's counsel wouldn't want to sit in a room with someone possibly exposed to a lethal virus. But here, Plaintiff's counsel filed a brief suggesting that the entire thing was bogus. "Theodore's counsel cancelled the deposition because of he [sic] claimed he was exposed to Covid-19.... Plaintiff's counsel found the last minute cancellation suspect.... " That response landed poorly with the Court. It lacked empathy, and unnecessarily impugned the integrity of a member of the bar. It was especially troubling given that the underlying issue involves a very real, very serious public health threat. And it involved a member of Becker's family. By December 16, 2021, Plaintiff's counsel must file a statement and reveal whether Plaintiff's counsel had any specific reason to doubt the candor of counsel about a family member contracting the virus. If not, then the Court suggests a moment of quiet reflection, and encourages counsel to view the filing as a good opportunity for offering an apology.

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Sun, 28 May 2023

The Master of the Pecos River returns

Lately I have been enjoying Adam Unikowsky's Legal Newsletter which is thoughtful, informative, and often very funny.

For example a recent article was titled “Why does doctrine get so complicated?”:

After reading Reed v. Goertz, one gets the feeling that the American legal system has failed. Maybe Reed should get DNA testing and maybe he shouldn’t. But whatever the answer to this question, it should not turn on Article III, the Rooker-Feldman doctrine, sovereign immunity, and the selection of one from among four different possible accrual dates. Some disputes have convoluted facts, so one would expect the legal analysis to be correspondingly complex. But this dispute is simple. Reed says DNA testing would prove his innocence. The D.A. says it wouldn’t. If deciding this dispute requires the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve four difficult antecedent procedural issues, something has gone awry.

Along the way Unikowsky wanted to support that claim that:

law requires the shallowest degree of subject-matter expertise of any intellectual profession

and, comparing the law with fields such as medicine, physics or architecture which require actual expertise, he explained:

After finishing law school, many law students immediately become judicial law clerks, in which they are expected to draft judicial opinions in any area of law, including areas to which they had zero exposure in law school. If a judge asks a law clerk to prepare a judicial opinion in (say) an employment discrimination case, and the student expresses concern that she did not take Employment Law in law school, the judge will assume that the law clerk is making a whimsical joke.

I laughed at that.

Anyway, that was not what I planned to talk about. For his most recent article, Unikowsky went over all the United States Supreme Court cases from the last ten years, scored them on a five-axis scale of interestingness and importance, and published his rankings of the least significant cases of the decade”.

Reading this was a little bit like the time I dropped into Reddit's r/notinteresting forum, which I joined briefly, and then quit when I decided it was not interesting.

I think I might have literally fallen asleep while reading about U.S. Bank v. Lakeridge, despite Unikowsky's description of it as “the weirdest cert grant of the decade”:

There was some speculation at the time that the Court meant to grant certiorari on the substantive issue of “what’s a non-statutory insider?” but made a typographical error in the order granting certiorari, but didn’t realize its error until after the baffled parties submitted their briefs, after which the Court decided, whatever, let’s go with it.

Even when the underlying material was dull, Unikowsky's writing was still funny and engaging. There were some high points. Check out his description of the implications of the decision in Amgen, or the puzzled exchange between Justice Sotomayor and one of the attorneys in National Association of Manufacturers.

But one of the cases on his list got me really excited:

The decade’s least significant original-jurisdiction case, selected from a small but august group of contenders, was Texas v. New Mexico, 141 S. Ct. 509 (2020). In 1988, the Supreme Court resolved a dispute between Texas and New Mexico over equitable apportionment of the Pecos River’s water.

Does this ring a bell? No? I don't know that many Supreme Court cases, but I recognized that one. If you have been paying attention you will remember that I have blogged about it before!

I love when this happens. It is bit like when you have a chance meeting with a stranger while traveling in a foreign country, spend a happy few hours with them, and then part, expecting never to see them again, but then years later you are walking in a different part of the world and there they are going the other way on the same sidewalk.

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Sat, 01 Apr 2023

Human organ trafficking in Indiana

The Indiana General Assembly has an excellent web site for the Indiana state code. Looking up something else, I learned the following useful tidbit:

IC 35-46-5-1 Human organ trafficking

Sec. 1. (a) As used in this section, "human organ" means the kidney, liver, heart, lung, cornea, eye, bone marrow, bone, pancreas, or skin of a human body.

So apparently, the trafficking of human gall bladders is A-OK in Indiana.

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

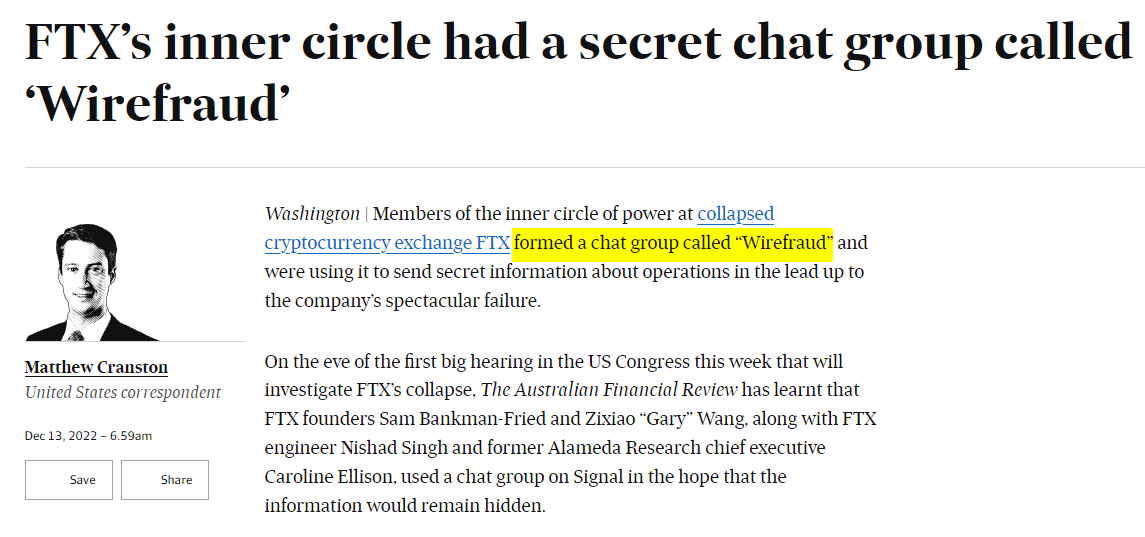

Tue, 13 Dec 2022A while back I wrote about how Katara disgustedly reported that some of her second-grade classmates had formed a stealing club and named it “Stealing Club”.

Anyway,

(Original source: Australian Financial Review)

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Thu, 21 Apr 2022

Pushing back against contract demands is scary but please try anyway

A year or two ago I wrote a couple of articles about the importance of pushing back against unreasonable contract provisions before you sign the contract. [1: Strategies] [2: Examples]

My last two employers have unintentionally had deal-breaker clauses in contracts they wanted me to sign before starting employment. Both were examples I mentioned in the previous article about things you should never agree to. One employer asked me to yield ownership of my entire work product during the term of my employment, including things I wrote on my own time on my own equipment, such as these blog articles. I think the employer should own only the things they pay me to create, during my working hours.

When I pointed this out to them I got a very typical reply: “Oh, we don't actually mean that, we only want to own things you produced in the scope of your employment.” What they said they wanted was what I also wanted.

This typical sort of reply is almost always truthful. That is all they want. It's important to realize that your actual interests are aligned here! The counterparty honestly does agree with you.

But you mustn't fall into the trap of signing the contract anyway, with the idea that you both understand the real meaning and everything will be okay. You may agree today, but that can change. The company's management or ownership can change. Suppose you are an employee of the company for many years, it is very successful, it goes public, and the new Board of Directors decides to exert ownership of your blog posts? Then the oral agreement you had with the founder seven years before will be worth the paper it is not printed on. The whole point of a written contract is that it can survive changes of agency and incentive.

So in this circumstance, you should say “I'm glad we are in agreement on this. Since you only want ownership of work produced in the scope of my employment, let's make sure the contract says that.”

If they continue to push back, try saying innocently “I don't understand why you would want to have X in the written agreement if what you really want is Y.” (It could be that they really do want X despite their claims otherwise. Wouldn't it be good to find that out before it was too late to back out?)

Pushing back against incorrect contract clauses can be scary. You want the job. You are probably concerned that the whole deal will fall through because of some little contract detail. You may be concerned that you are going to get a reputation as a troublemaker before you even start the job. It's very uncomfortable, and it's hard to be brave. But this is a better-than-usual place to try to be brave, not just for yourself.

If the employer is a good one, they want the contract to be fair, and if the contract is unfair it's probably by accident. But they have a million other things to do other than getting the legal department to fix the contract, so it doesn't get fixed, simply because of inertia.

If, by pushing back, you can get the employer to fix their contract, chances are it will stay fixed for everyone in the future also, simply because of inertia. People who are less experienced, or otherwise in a poorer negotiating position than you were, will be able to enjoy the benefits that you negotiated. You're negotiating not just for yourself but for the others who will follow you.

And if you are like me and you have a little more power and privilege than some of the people who will come after, this is a great place to apply some of it. Power and privilege can be used for good or bad. If you have some, this is a situation where you can use some for good.

It still scary! In this world of giant corporations that control everything, each of us is a tiny insect, hoping not to be heedlessly trampled. I am afraid to bargain with such monsters. But I know that as a middle-aged white guy with experience and savings and a good reputation, I have the luxury of being able to threaten to walk away from a job offer over an unfair contract clause. This is an immense privilege and I don't want to let it go to waste.

We should push back against unfair conditions pressed on us by corporations. It can be frightening and risky to do this, because they do have more power than we do. But we all deserve fairness. If it seems too risky to demand fair treatment for yourself, perhaps draw courage from the thought that you're also helping to make things more fair for other people. We tiny insects must all support one another if we are to survive with dignity.

[ Addendum 20220424: A correspondent says: “I also have come to hate articles like yours because they proffer advice to people with the least power to do anything.” I agree, and I didn't intend to write another one of those. My idea was to address the article to middle-aged white guys like me, who do have a little less risk than many people, and exhort them to take the chance and try to do something that will help people. In the article I actually wrote, this point wasn't as prominent as I meant it to be. Writing is really hard. ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Tue, 15 Dec 2020The world is so complicated! It has so many things in it that I could not even have imagined.

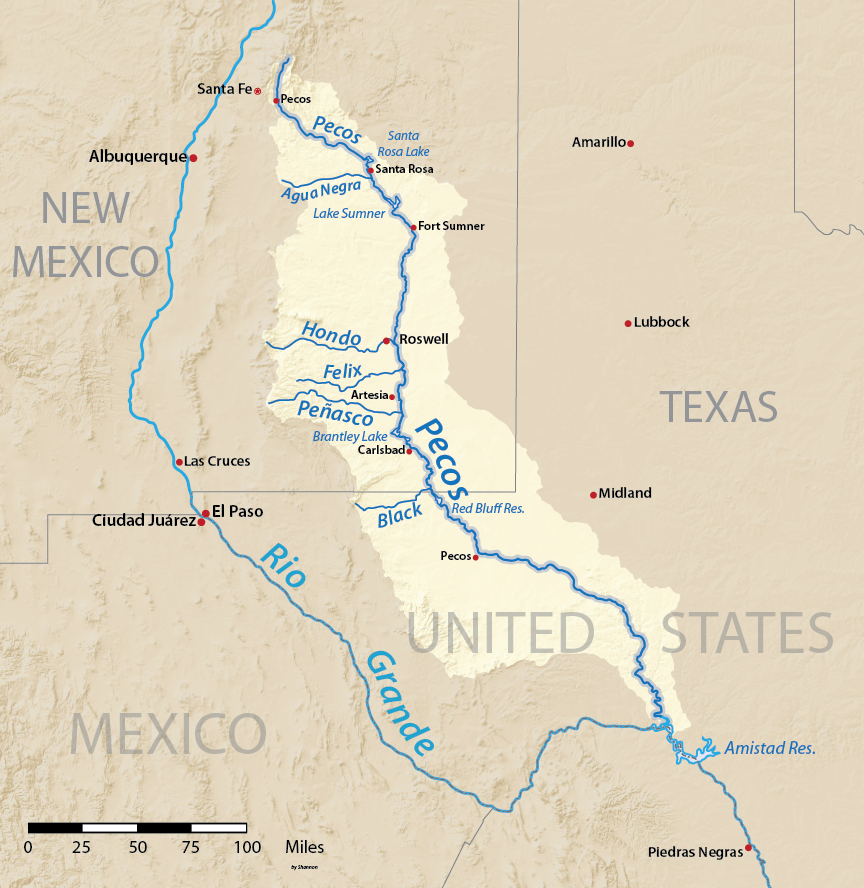

Yesterday I learned that since 1949 there has been a compact between New Mexico and Texas about how to divide up the water in the Pecos River, which flows from New Mexico to Texas, and then into the Rio Grande.

New Mexico is not allowed to use all the water before it gets to Texas. Texas is entitled to receive a certain amount.

There have been disputes about this in the past (the Supreme Court case has been active since 1974), so in 1988 the Supreme Court appointed Neil S. Grigg, a hydraulic engineer and water management expert from Colorado, to be “River Master of the Pecos River”, to mediate the disputes and account for the water. The River Master has a rulebook, which you can read online. I don't know how much Dr. Grigg is paid for this.

In 2014, Tropical Storm Odile dumped a lot of rain on the U.S. Southwest. The Pecos River was flooding, so Texas asked NM to hold onto the Texas share of the water until later. (The rulebook says they can do this.) New Mexico arranged for the water that was owed to Texas to be stored in the Brantley Reservoir.

A few months later Texas wanted their water. "OK," said New Mexico. “But while we were holding it for you in our reservoir, some of it evaporated. We will give you what is left.”

“No,” said Texas, “we are entitled to a certain amount of water from you. We want it all.”

But the rule book says that even though the water was in New Mexico's reservoir, it was Texas's water that evaporated. (Section C5, “Texas Water Stored in New Mexico Reservoirs”.)

[ Addendum 20230528: To my amazement this case has come to my attention again, because legal blogger Adam Unikowsky cited it as one of “the [ten] least significant cases of the decade”. I wrote a brief followup about why I enjoy Unikowsky's Legal Newsletter. ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Thu, 11 Jun 2020

Malicious trojan horse code hidden in large patches

This article isn't going to be fun to write but I'm going to push through it because I think it's genuinely important. How often have you heard me say that?

A couple of weeks ago the Insurrection Act of 1807 was in the news. I noticed that the Wikipedia article about it contained this very strange-seeming claim:

A secret amendment was made to the Insurrection Act by an unknown Congressional sponsor, allowing such intervention against the will of state governors.

“What the heck is a ‘secret amendment’?” I asked myself. “Secret from whom? Sounds like Wikipedia crackpottery.” But there was a citation, so I could look to see what it said.

The citation is Hoffmeister, Thaddeus (2010). "An Insurrection Act for the Twenty-First Century". Stetson Law Review. 39: 898.

Sometimes Wikipedia claims will be accompanied by an authoritative-seeming citation — often lacking a page number, as this one did at the time — that doesn't actually support the claim. So I checked. But Hoffmeister did indeed make that disturbing claim:

Once finalized, the Enforcement Act was quietly tucked into a large defense authorization bill: the John Warner Defense Authorization Act of 2007. Very few people, including many members of Congress who voted on the larger defense bill, actually knew they were also voting to modify the Insurrection Act. The secrecy surrounding the Enforcement Act was so pervasive that the actual sponsor of the new legislation remains unknown to this day.

I had sometimes wondered if large, complex acts such as HIPAA or the omnibus budget acts sometimes contained provisions that were smuggled into law without anyone noticing. I hoped that someone somewhere was paying attention, so that it couldn't happen.

But apparently the answer is that it does.

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Tue, 28 Jan 2020Today I learned that James Blaine (U.S. Speaker of the House, senator, perennial presidential candidate, and Secretary of State under Presidents Cleveland, Garfield, and Arthur; previously) was the namesake of the notorious “Blaine Amendments”. These are still an ongoing legal issue!

The Blaine Amendment was a proposed U.S. constitutional amendment rooted in anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant sentiment, at a time when the scary immigrant bogeymen were Irish and Italian Catholics.

The amendment would have prevented the U.S. federal government from providing aid to any educational institution with a religious affiliation; the specific intention was to make Catholic parochial schools ineligible for federal education funds. The federal amendment failed, but many states adopted it and still have it in their state constitutions.

Here we are 150 years later and this is still an issue! It was the subject of the 2017 Supreme Court case Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer. My quick summary is:

The Missouri state Department of Natural Resources had a program offering grants to licensed daycare facilities to resurface their playgrounds with shredded tires.

In 2012, a daycare facility operated by Trinity Lutheran church ranked fifth out of 44 applicants according to the department’s criteria.

14 of the 44 applicants received grants, but Trinity Lutheran's daycare was denied, because the Missouri constitution has a Blaine Amendment.

The Court found (7–2) that denying the grant to an otherwise qualified daycare just because of its religious affiliation was a violation of the Constitution's promises of free exercise of religion. (Full opinion)

It's interesting to me that now that Blaine is someone I recognize, he keeps turning up. He was really important, a major player in national politics for thirty years. But who remembers him now?

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Thu, 16 Jan 2020

A serious proposal to exploit the loophole in the U.S. Constitution

In 2007 I described an impractical scheme to turn the U.S. into a dictatorship, or to make any other desired change to the Constitution, by having Congress admit a large number of very small states, which could then ratify any constitutional amendments deemed desirable.

An anonymous writer (probably a third-year law student) has independently discovered my scheme, and has proposed it as a way to “fix” the problems that they perceive with the current political and electoral structure. The proposal has been published in the Harvard Law Review in an article that does not appear to be an April Fools’ prank.

The article points out that admission of new states has sometimes been done as a political hack. It says:

Republicans in Congress were worried about Lincoln’s reelection chances and short the votes necessary to pass the Thirteenth Amendment. So notwithstanding the traditional population requirements for statehood, they turned the territory of Nevada — population 6,857 — into a state, adding Republican votes to Congress and the Electoral College.

Specifically, the proposal is that the new states should be allocated out of territory currently in the District of Columbia (which will help ensure that they are politically aligned in the way the author prefers), and that a suitable number of new states might be one hundred and twenty-seven.

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Fri, 13 Dec 2019

California corpse-tampering law

[ Content warning: dead bodies, sex crime, just plain nasty ]

A co-worker brought this sordid item to my attention: LAPD officer charged after allegedly fondling a dead woman's breast.

[A] Los Angeles Police Department officer … was charged Thursday with one felony count of having sexual contact with human remains without authority, officials said, after he allegedly fondled a dead woman's breast.

[The officer] was alone in a room with the deceased woman while his partner went to get paper work from a patrol car…. At that point, [he] turned off the body camera and inappropriately touched the woman. … A two-minute buffer on the camera captured the incident even though [he] had turned it off.

Yuck.

Chas. Owens then asked a very good question:

Okay, no one is commenting on “sexual contact with human remains without authority”

How does one go about getting authority to have sexual contact with human remains?

Is there a DMV for necrophiles?

I tried to resist this nerdsnipe, but I was unsuccessful. I learned that California does have a law on the books that makes it a felony to have unauthorized sex with human remains:

HEALTH AND SAFETY CODE - HSC

DIVISION 7. DEAD BODIES [7000 - 8030]

PART 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS [7000 - 7355]

CHAPTER 2. General Provisions [7050.5 - 7055]7052.

(a) Every person who willfully mutilates, disinters, removes from the place of interment, or commits an act of sexual penetration on, or has sexual contact with, any remains known to be human, without authority of law, is guilty of a felony. This section does not apply to any person who, under authority of law, removes the remains for reinterment, or performs a cremation.

…

(b)(2) “Sexual contact” means any willful touching by a person of an intimate part of a dead human body for the purpose of sexual arousal, gratification, or abuse.

(California HSC, section 7052)

I think this addresses Chas.’s question. Certainly there are other statutes that authorize certain persons to disinter or mutilate corpses for various reasons. (Inquests, for example.) A defendant wishing to take advantage of this exception would have to affirmatively claim that he was authorized to grope the corpse’s breast, and by whom. I suppose he could argue that the state had the burden of proof to show that he had not been authorized to fondle the corpse, but I doubt that many jurors would find this persuasive.

Previously on this blog: Legal status of corpses in 1911 England.

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Thu, 03 Oct 2019

The pain of tracking down changes in U.S. law

Last month when I was researching my article about the free coffee provision in U.S. federal highway law, I spent a great deal of time writing this fragment:

I knew that the provision was in 23 USC §131, but I should explain what this means.

The body of U.S. statutory law can be considered a single giant document, which is "codified" as the United States Code, or USC for short. USC is divided into fifty or sixty “titles” or subject areas, of which the relevant one here, title 23, concerns “Highways”. The titles are then divided into sections (the free coffee is in section 131), paragraphs, sub-paragraphs, and so on, each with an identifying letter. The free coffee is 23 USC §131 (c)(5).

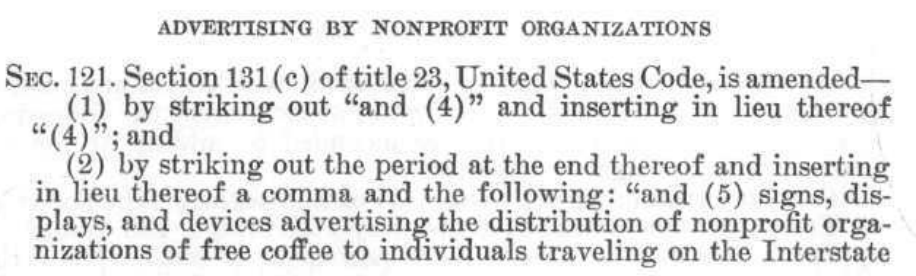

But this didn't tell me when the coffee exception was introduced or in what legislation. Most of Title 23 dates from 1958, but the coffee sign exception was added later. When Congress amends a law, they do it by specifying a patch to the existing code. My use of the programmer jargon term “patch” here is not an analogy. The portion of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1978 that enacted the “free coffee” exception reads as follows:

ADVERTISING BY NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

Sec. 121. Section 131(c) of title 23, United States Code, is amended—

(1) by striking out “and (4)” and inserting in lieu thereof “(4)”; and

(2) by striking out the period at the end thereof and inserting in lieu thereof a comma and the following: “and (5) signs, displays, and devices advertising the distribution of nonprofit organizations of free coffee […]”.

(The “[…]” is my elision. The Act includes the complete text that was to be inserted.)

The act is not phrased as a high-level functional description, such as “extend the list of exceptions to include: ... ”. It says to replace the text ‘and (4)’ with the text ‘(4)’; then replace the period with a comma; then …”, just as if Congress were preparing a patch in a version control system.

Unfortunately, the lack of an actual version control system makes it quite hard to find out when any particular change was introduced. The code page I read is provided by the Legal Information Institute at Cornell University. At the bottom of the page, there is a listing of the changes that went into this particular section:

(Pub. L. 85–767, Aug. 27, 1958, 72 Stat. 904; Pub. L. 86–342, title I, § 106, Sept. 21, 1959, 73 Stat. 612; Pub. L. 87–61, title I, § 106, June 29, 1961, 75 Stat. 123; Pub. L. 88–157, § 5, Oct. 24, 1963, 77 Stat. 277; Pub. L. 89–285, title I, § 101, Oct. 22, 1965, 79 Stat. 1028; Pub. L. 89–574, § 8(a), Sept. 13, 1966, 80 Stat. 768; Pub. L. 90–495, § 6(a)–(d), Aug. 23, 1968, 82 Stat. 817; Pub. L. 91–605, title I, § 122(a), Dec. 31, 1970, 84 Stat. 1726; Pub. L. 93–643, § 109, Jan. 4, 1975, 88 Stat. 2284; Pub. L. 94–280, title I, § 122, May 5, 1976, 90 Stat. 438; Pub. L. 95–599, title I, §§ 121, 122, Nov. 6, 1978, 92 Stat. 2700, 2701; Pub. L. 96–106, § 6, Nov. 9, 1979, 93 Stat. 797; Pub. L. 102–240, title I, § 1046(a)–(c), Dec. 18, 1991, 105 Stat. 1995, 1996; Pub. L. 102–302, § 104, June 22, 1992, 106 Stat. 253; Pub. L. 104–59, title III, § 314, Nov. 28, 1995, 109 Stat. 586; Pub. L. 105–178, title I, § 1212(a)(2)(A), June 9, 1998, 112 Stat. 193; Pub. L. 112–141, div. A, title I, §§ 1519(c)(6), formerly 1519(c)(7), 1539(b), July 6, 2012, 126 Stat. 576, 587, renumbered § 1519(c)(6), Pub. L. 114–94, div. A, title I, § 1446(d)(5)(B), Dec. 4, 2015, 129 Stat. 1438.)

Whew.

Each of these is a citation of a particular Act of Congress. For example, the first one

Pub. L. 85–767, Aug. 27, 1958, 72 Stat. 904

refers to “Public law 85–767”, the 767th law enacted by the 85th Congress, which met during the Eisenhower administration, from 1957–1959. The U.S. Congress has a useful web site that contains a list of all the public laws, with links — but it only goes back to the 93rd Congress of 1973–1974.

And anyway, just knowing that it is Public law 85–767 is not (or was not formerly) enough to tell you how to look up its text. The laws must be published somewhere before they are codified, and scans of these publications, the United States Statutes at Large, are online back to the 82nd Congress. That is what the “72 Stat. 904” means: the publication was in volume 72 of the Statutes at Large, page 904. This citation style was obviously designed at a time when the best (or only) way to find the statute was to go down to the library and pull volume 72 off the shelf. It is well-designed for that purpose. Now, not so much.

Here's a screengrab of the relevant portion of the relevant part of the 1978 act:

The citation for this was:

Pub. L. 95–599, title I, §§ 121, 122, Nov. 6, 1978, 92 Stat. 2700, 2701

(Note that “title I, §§ 121, 122” here refers to the sections of the act itself, not the section of the US Code that was being amended; that was title 23, §131, remember.)

To track this down, I had no choice but to grovel over each of the links to the Statutes at Large, download each scan, and search over each one looking for the coffee provision. I kept written notes so that I wouldn't mix up the congressional term numbers with the Statutes volume numbers.

It ought to be possible, at least in principle, to put the entire U.S. Code into a version control system, with each Act of Congress represented as one or more commits, maybe as a merged topic branch. The commit message could contain the citation, something like this:

commit a4e2b2a1ca2d5245c275ddef55bf8169d72580df

Merge: 6829b2dd986 836108c2ba0

Author: ... <...>

Date: Mon Nov 6 00:00:00 1978 -0400

Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1978

P.L. 95–599

92 Stat. 2689–2762

H.R. 11733

Merge branch `pl-95-599` to `master`

commit 836108c2ba0d5245c275ddef55bf8169d72580df

Author: ... <...>

Date: Mon Nov 6 00:00:00 1978 -0400

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1978 (section 121)

(Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1978, title I)

P.L. 95–599

92 Stat. 2689–2762

H.R. 11733

Signs advertising free coffee are no longer prohibited

within 660 feet of a federal highway.

diff --git a/USC/title23.md b/USC/title23.md

index 084bfc2..caa5a53 100644

--- a/USC/title23.md

+++ b/USC/title23.md

@@ -20565,11 +20565,16 @@ 23 U.S. Code § 131. Control of outdoor advertising

be changed at reasonable intervals by electronic process or by remote

control, advertising activities conducted on the property on which

-they are located, and (4) signs lawfully in existence on October 22,

+they are located, (4) signs lawfully in existence on October 22,

1965, determined by the State, subject to the approval of the

Secretary, to be landmark signs, including signs on farm structures or

natural surfaces, or historic or artistic significance the

preservation of which would be consistent with the purposes of this

-section.

+section, and (5) signs, displays, and devices advertising the

+distribution by nonprofit organizations of free coffee to individuals

+traveling on the Interstate System or the primary system. For the

+purposes of this subsection, the term “free coffee” shall include

+coffee for which a donation may be made, but is not required.

+

*(d)* In order to promote the reasonable, orderly and effective

Or maybe the titles would be directories and the sections would be numbered files in those directories. Whatever. If this existed, I would be able to do something like:

git log -Scoffee -p -- USC/title23.md

and the Act that I wanted would pop right out.

Preparing a version history of the United States Code would be a dauntingly large undertaking, but gosh, so useful. A good VCS enables you to answer questions that you previously wouldn't have even thought of asking.

This article started as a lament about how hard it was for me to track down the provenance of the coffee exception. But it occurs to me that this is the response of someone who has been spoiled by plenty. A generation ago it would have been unthinkable for me even to try to track this down. I would have had to start by reading a book about legal citations and learning what “79 Stat. 1028” meant, instead of just picking it up on the fly. Then I would have had to locate a library with a set of the Statutes at Large and travel to it. And here I am complaining about how I had to click 18 links and do an (automated!) text search on 18 short, relevant excerpts of the Statutes at Large, all while sitting in my chair.

My kids can't quite process the fact that in my childhood, you simply didn't know what the law was and you had no good way to find out. You could go down to the library, take the pertinent volumes of the USC off the shelf, and hope you had looked in all the appropriate places for the relevant statutes, but you could never be sure you hadn't overlooked something. OK, well, you still can't be sure, but now you can do keyword search, and you can at least read what it does say without having to get on a train.

Truly, we live in an age of marvels.

[ Addendum 20191004: More about this ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Wed, 02 Oct 2019Last month I mentioned that, while federal law generally prohibits signs and billboards about signs within ⅛ mile of a federal highway, signs offering free coffee are allowed.

Vilhelm Sjöberg brought to my attention the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Reed v. Town of Gilbert. Under the Reed logic, the exemption for free coffee may actually be unconsitutional. The majority's opinion states, in part:

The Sign Code is content based on its face. It defines the categories of temporary, political, and ideological signs on the basis of their messages and then subjects each category to different restrictions. The restrictions applied thus depend entirely on the sign’s communicative content.

The court concluded that the Sign Code (of the town of Gilbert, AZ) was therefore subject to the very restrictive standard of strict scrutiny, which required that it be struck down unless the government could demonstrate both that it was necessary to a “compelling state interest” and that it be “narrowly tailored” to achieving that interest. The Gilbert Sign Code did not survive this analysis.

Although the court unanimously struck down the Sign Code, a concurrence, written by Justice Kagan and joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, faulted the majority's reasoning:

On the majority’s view, courts would have to determine that a town has a compelling interest in informing passersby where George Washington slept. And likewise, courts would have to find that a town has no other way to prevent hidden-driveway mishaps than by specially treating hidden-driveway signs. (Well-placed speed bumps? Lower speed limits? Or how about just a ban on hidden driveways?)

Kagan specifically mentioned the “free coffee” exception as being one of many that would be imperiled by the court's reasoning in this case.

Thanks very much to M. Sjöberg for pointing this out.

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Mon, 16 Sep 201923 USC §131 controls the display of billboards and other signs within 660 feet of a federal interstate highway. As originally enacted in 1965, there were a few exceptions, such as directional signs, and signs advertising events taking place on the property on which they stood, or the sale or lease of that property.

Today I learned that under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1978, the list of exceptions was extended to include:

signs, displays, and devices advertising the distribution by nonprofit organizations of free coffee to individuals traveling on the Interstate System or the primary system.

There is no exception for free tea.

[ Addendum 20191002: A 2015 Supreme Court decision imperils the free coffee exception, according to three of the justices. I've written a detailed followup. ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Sat, 09 Dec 2017The Volokh Conspiracy is a frequently-updated blog about legal issues. It reports on interesting upcoming court cases and recent court decisions and sometimes carries thoughtful and complex essays on legal theory. It is hosted by, but not otherwise affiliated with, the Washington Post.

Volokh periodically carries a “roundup of recent federal court decisions”, each with an intriguing one-paragraph summary and a link to the relevant documents, usually to the opinion itself. I love reading federal circuit court opinions. They are almost always carefully thought out and clearly-written. Even when I disagree with the decision, I almost always concede that the judges have a point. It often happens that I read the decision and say “of course that is how it must be decided, nobody could disagree with that”, and then I read the dissenting opinion and I say exactly the same thing. Then I rub my forehead and feel relieved that I'm not a federal circuit court judge.

This is true of U.S. Supreme Court decisions also. Back when I had more free time I would sometimes visit the listing of all recent decisions and pick out some at random to read. They were almost always really interesting. When you read the newspaper about these decisions, the newspaper always wants to make the issue simple and usually tribal. (“Our readers are on the (Red / Blue) Team, and the (Red / Blue) Team loves mangel-wurzels. Justice Furter voted against mangel-wurzels, that is because he is a very bad man who hates liberty! Rah rah team!”) The actual Supreme Court is almost always better than this.

For example we have Clarence Thomas's wonderful dissent in the case of Gonzales v. Raich. Raich was using marijuana for his personal medical use in California, where medical marijuana had been legal for years. The DEA confiscated and destroyed his supplier's plants. But the Constitution only gives Congress the right to regulate interstate commerce. This marijuana had been grown in California by a Californian, for use in California by a Californian, in accordance with California law, and had never crossed any state line. In a 6–3 decision, the court found that the relevant laws were nevertheless a permitted exercise of Congress's power to regulate commerce. You might have expected Justice Thomas to vote against marijuana. But he did not:

If the majority is to be taken seriously, the Federal Government may now regulate quilting bees, clothes drives, and potluck suppers throughout the 50 States. This makes a mockery of Madison’s assurance to the people of New York that the “powers delegated” to the Federal Government are “few and defined,” while those of the States are “numerous and indefinite.”

Thomas may not be a fan of marijuana, but he is even less a fan of federal overreach and abuse of the Commerce Clause. These nine people are much more complex than the newspapers would have you believe.

But I am digressing. Back to Volokh's federal court roundups. I have to be careful not to look at these roundups when I have anything else that must be done, because I inevitably get nerdsniped and read several of them. If you enjoy this kind of thing, this is the kind of thing you will enjoy.

I want to give some examples, but can't decide which sound most interesting, so here are three chosen at random from the most recent issue:

Warden at Brooklyn, N.Y., prison declines prisoner’s request to keep stuffed animals. A substantial burden on the prisoner’s sincere religious beliefs?

Online reviewer pillories Newport Beach accountant. Must Yelp reveal the reviewer’s identity?

With no crosswalks nearby, man jaywalks across five-lane avenue, is struck by vehicle. Is the church he was trying to reach negligent for putting its auxiliary parking lot there?

[ Addendum 20171213: Volokh has just left the Washington Post, and moved to Reason, citing changes in the Post's paywall policies. ]

[ Addendum 20210628: Much has changed since Gonzales v. Raich, and today Justice Thomas observed that even if the majority's argument stood up in 2004, justified by the Necessary and Proper clause, it no longer does, as the federal government no longer appears consider the prohibition of marijuana necessary or proper. ]

[ Addendum 20231218: This article lacks a clear, current link to the Short Circuit summaries that it discusses. Here's an index of John Ross' recent Short Circuit posts. ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Sat, 21 Mar 2015

Examples of contracts you should not sign

Shortly after I posted A public service announcement about contracts Steve Bogart asked me on on Twitter for examples of dealbreaker clauses. Some general types I thought of immediately were:

Any nonspecific non-disclosure agreement with a horizon more than three years off, because after three years you are not going to remember what it was that you were not supposed to disclose.

Any contract in which you give up your right to sue the other party if they were to cheat you.

Most contracts in which you permanently relinquish your right to disparage or publicly criticize the other party.

Any contract that leaves you on the hook for the other party's losses if the project is unsuccessful.

Any contract that would require you to do something immoral or unethical.

Addendum 20150401: Chas. Owens suggests, and I agree, that you not sign a contract that gives the other party ownership of everything you produce, even including things you created on your own time with your own equipment.

A couple of recent specific examples:

Comcast is negotiating a contract with our homeowner's association to bring cable Internet to our village; the proposed agreement included a clause in which we promised not to buy Internet service from any other company for the next ten years. I refused to sign. The guy on our side who was negotiating the agreement was annoyed with me. If too many people refuse to sign, maybe Comcast will back out. “Do you think you're going to get FIOS in here in the next ten years?” he asked sarcastically. “No,” I said. “But I might move.”

Or, you know, I might get sick of Comcast and want to go back to whatever I was using before. Or my satellite TV provider might start delivering satellite Internet. Or the municipal wireless might suddenly improve. Or Google might park a crazy Internet Balloon over my house. Or some company that doesn't exist yet might do something we can't even imagine. Google itself is barely ten years old! The iPhone is only eight!

In 2013 I was on a job interview at company X and was asked to sign an NDA that enjoined me from disclosing anything I learned that day for the next ten years. I explained that I could not sign such an agreement because I would not be able to honor it. I insisted on changing it to three years, which is also too long, but I am not completely unwilling to compromise. It's now two years later and I have completely forgotten what we discussed that day; I might be violating the NDA right now for all I know. Had they insisted on ten years, would I have walked out? You bet I would. You don't let your mouth write checks that your ass can't cash.

[ Addendum 20191107: Our FIOS was installed in January of 2018. Lucky I hadn't signed that ten-year contract, huh? ]

[ Addendum 20220420: More about why it's important to push back ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Fri, 20 Mar 2015

A public service announcement about contracts

Every so often, when I am called upon to sign some contract or other, I have a conversation that goes like this:

Me: I can't sign this contract; clause 14(a) gives you the right to chop off my hand.

Them: Oh, the lawyers made us put that in. Don't worry about it; of course we would never exercise that clause.

There is only one response you should make to this line of argument:

Well, my lawyer says I can't agree to that, and since you say that you would never exercise that clause, I'm sure you will have no problem removing it from the contract.

Because if the lawyers made them put in there, that is for a reason. And there is only one possible reason, which is that the lawyers do, in fact, envision that they might one day exercise that clause and chop off your hand.

The other party may proceed further with the same argument: “Look, I have been in this business twenty years, and I swear to you that we have never chopped off anyone's hand.” You must remember the one response, and repeat it:

Great! Since you say that you have never chopped off anyone's hand, then you will have no problem removing that clause from the contract.

You must repeat this over and over until it works. The other party is lazy. They just want the contract signed. They don't want to deal with their lawyers. They may sincerely believe that they would never chop off anyone's hand. They are just looking for the easiest way forward. You must make them understand that there is no easier way forward than to remove the hand-chopping clause.

They will say “The deadline is looming! If we don't get this contract executed soon it will be TOO LATE!” They are trying to blame you for the blown deadline. You should put the blame back where it belongs:

As I've made quite clear, I can't sign this contract with the hand-chopping clause. If you want to get this executed soon, you must strike out that clause before it is TOO LATE.

And if the other party would prefer to walk away from the deal rather than abandon their hand-chopping rights, what does that tell you about the value they put on the hand-chopping clause? They claim that they don't care about it and they have never exercised it, but they would prefer to give up on the whole project, rather than abandon hand-chopping? That is a situation that is well worth walking away from, and you can congratulate yourself on your clean escape.

[ Addendum: Steve Bogart asked on Twitter for examples of unacceptable contract demands; I thought of so many that I put them in a separate article. ]

[ Addendum 20150401: Chas. Owens points out that you don't have to argue about it; you can just cross out the hand-chopping clause, add your initials and date in the margin. I do this also, but then I bring the modification it to the other party's attention, because that is the honest and just thing to do. ]

[ Addendum 20220420: More and more, contracts are moving online and getting electronic signatures. This removes the option to modify the contract before signing: you can sign it intact, or not at all. Don't ever forget that the Man is always trying to get his foot on your neck. ]

[ Addendum 20220420: More about why it's important to push back ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Wed, 15 Aug 2012

The weird ethics of life insurance

Many life insurance policies, including my own, include a clause that

says that they will not pay out in case of suicide. This not only

reduces the risk to the insurance company, it also removes an

important conflict of interest from the client. I own a life

insurance policy, and I am glad that I do not have this conflict of

interest, which, as I suffer from chronic depression, would only add

to my difficulties.

Without this clause, the insurance company might find itself in the business of enabling suicide, or even of encouraging people to commit suicide. Completely aside from any legal or financial problems this would cause for them, it is a totally immoral position to be in, and it is entirely creditable that they should try to avoid it.

But enforcement of suicide clauses raises some problems. The insurance company must investigate possible suicides, and enforce the suicide clauses, or else they have no value. So the company pays investigators to look into claims that might be suicides, and if their investigators determine that a death was due to suicide, the company must refuse to pay out. I will repeat that: the insurance company has a moral obligation to refuse to pay out if, in their best judgment, the death was due to suicide. Otherwise they are neglecting their duty and enabling suicide.

But the company's investigators will not always be correct. Even if their judgments are made entirely in good faith, they will still sometimes judge a death to be suicide when it wasn't. Then the decedent's grieving family will be denied the life insurance benefits to which they are actually entitled.

So here we have a situation in which even if everyone does exactly what they should be doing, and behaves in the most above-board and ethical manner possible, someone will inevitably end up getting horribly screwed.

[ Addendum 20120816: It has been brought to my attention that this post constains significant omissions and major factual errors. I will investigate further and try to post a correction. ]

Addendum 20220422: I never got around to the research, but the short summary is, the suicide determination is not made by the insurance company, but by the county coroner, who is independent of the insurer. This does point the way to a possible exploit, that the insurer could bribe or otherwise suborn the coroner. But this sort of exploit is present in all systems. My original point, that the hypothetical insurance company investigators would have a conflict of interest, has been completely addressed. ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Wed, 21 Jan 2009

The loophole in the U.S. Constitution: recent developments

Some time ago I wrote a couple of articles [1]

[2]

on the famous story that

Kurt Gödel claimed to have found a loophole in the United States

Constitution through which the U.S. could have become a dictatorship. I

proposed a couple of speculations about what Gödel's loophole

might have been, and reported on another one by

Peter Suber.

Recently Jeffrey Kegler wrote to inform me of some startling new developments on this matter. Although it previously appeared that the story was probably true, there was no firsthand evidence that it had actually occurred. The three witnesses would have been Philip Forman (the examining judge), Oskar Morgenstern and Albert Einstein. But, although Morgenstern apparently wrote up an account of the epsiode, it was lost.

Until now, that is. The Institute for Advanced Study (where Gödel, Einstein, and Morgenstern were all employed) posted an account on its web site, and M. Kegler was perceptive enough to realize that this account was probably written by someone who had access to the lost Morgenstern document but did not realize its significance. M. Kegler followed up the lead, and it turned out to be correct.

Kegler's Morgenstern website has a lot of additional detail, including the original document itself.

Now came an exciting development. [Gödel] rather excitedly told me that in looking at the Constitution, to his distress, he had found some inner contradictions, and he could show how in a perfectly legal manner it would be possible for somebody to become a dictator and set up a Fascist regime, never intended by those who drew up the Constitution.But before I let you get too excited about this, a warning: Morgenstern doesn't tell us what Gödel's loophole was! (Kegler's reading is that Morgenstern didn't care.) So although the truth of story has finally been proved beyond doubt, the central mystery remains.

The document is worth reading anyway. It's only three pages long, and it paints a fascinating picture of both Gödel, who is exactly the sort of obsessive geek that you always imagined he was, and of Einstein, who had a cruel streak that he was careful not to show to the public. Kegler's website is also worth reading for its insightful analysis of the lost document and its story.

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Wed, 12 Sep 2007

The loophole in the U.S. Constitution: the answer

In the previous

article, I wondered what "inconsistency in the Constitution" Gödel

might have found that would permit the United States to become a dictatorship.

Several people wrote in to tell me that Peter Suber addresses this in his book The Paradox of Self-Amendment, which is available online. (Suber also provides a provenance for the Gödel story.)

Apparently, the "inconsistency" noted by Gödel is simply that the Constitution provides for its own amendment. Suber says: "He noticed that the AC had procedural limitations but no substantive limitations; hence it could be used to overturn the democratic institutions described in the rest of the constitution." I am gravely disappointed. I had been hoping for something brilliant and subtle that only Gödel would have noticed.

Thanks to Greg Padgett, Julian Orbach, Simon Cozens, and Neil Kandalgaonkar for bringing this to my attention.

M. Padgett also pointed out that the scheme I proposed for amending the constitution, which I claimed would require only the cooperation of a majority of both houses of Congress, 218 + 51 = 269 people in all, would actually require a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate. He says that to be safe you would want all 100 senators to conspire; I'm not sure why 60 would not be sufficient. (Under current Senate rules, 60 senators can halt a filibuster.) This would bring the total required to 218 + 60 = 278 conspirators.

He also pointed out that the complaisance of five Supreme Court justices would give the President essentially dictatorial powers, since any legal challenge to Presidential authority could be rejected by the court. But this train of thought seems to have led both of us down the same path, ending in the idea that this situation is not really within the scope of the original question.

As a final note, I will point out what I think is a much more serious loophole in the Constitution: if the Vice President is impeached and tried by the Senate, then, as President of the Senate, he presides over his own trial. Article I, section 3 contains an exception for the trial of the President, where the Chief Justice presides instead. But the framers inexplicably forgot to extend this exception to the trial of the Vice President.

[ Addendum 20090121: Jeffrey Kegler has discovered Oskar Morgenstern's lost eyewitness account of Gödel's citizenship hearing. Read about it here. ]

[ Addendum 20110525: As far as I know, there is no particular reason to believe that Peter Suber's theory is correct. Morgenstern knew, but did not include it in his account. ]

[ Addendum 20160315: I thought of another interesting loophole in the Constitution: The Vice-President can murder the President, and then immediately pardon himself. ]

[ Addendum 20210210: As a result of this year's impeachment trial, it has come to my attention that the vice-president need not preside over senate impeachment trials. The senate can appoint anyone it wants to preside. ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Sun, 09 Sep 2007

The loophole in the U.S. Constitution

Gödel took the matter of citizenship with great solemnity, preparing for the exam by making a close study of the United States Constitution. On the eve of the hearing, he called [Oskar] Morgenstern in an agitated state, saying he had found an "inconsistency" in the Constitution, one that could allow a dictatorship to arise.(Holt, Jim. Time Bandits, The New Yorker, 29 February 2005.)

I've wondered for years what "inconsistency" was.

I suppose the Attorney General could bring some sort of suit in the Supreme Court that resulted in the Court "interpreting" the Constitution to find that the President had the power to, say, arbitrarily replace congresspersons with his own stooges. This would require only six conspirators: five justices and the President. (The A.G. is a mere appendage of the President and is not required for the scheme anyway.)

But this seems outside the rules. I'm not sure what the rules are, but having the Supreme Court radically and arbitrarily "re-interpret" the Constitution isn't an "inconsistency in the Constitution". The solution above is more like a coup d'etat. The Joint Chiefs of Staff could stage a military takeover and institute a dictatorship, but that isn't an "inconsistency in the Constitution" either. To qualify, the Supreme Court would have to find a plausible interpretation of the Constitution that resulted in a dictatorship.

The best solution I have found so far is this: Under Article IV, Congress has the power to admit new states. A congressional majority could agree to admit 150 trivial new states, and then propose arbitrary constitutional amendments, to be ratified by the trivial legislatures of the new states.

This would require a congressional majority in both houses. So Gödel's constant, the smallest number of conspirators required to legally transform the United States into a dictatorship, is at most 269. (This upper bound would have been 267 in 1948 when Gödel became a citizen.) I would like to reduce this number, because I can't see Gödel getting excited over a "loophole" that required so many conspirators.

[ Addendum 20070912: The answer. ]

[ Addendum 20090121: Jeffrey Kegler has discovered Oskar Morgenstern's lost eyewitness account of Gödel's citizenship hearing. Read about it here. ]

[ Addendum 20160129: F.E. Guerra-Pujol has written an article speculating on this topic, “Gödel’s Loophole”. Guerra-Pujol specifically rejects my Article IV proposal for requiring too many conspirators. ]

[ Addendum 20200116: The Harvard Law Review has published an article that proposes my scheme. ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link

Wed, 29 Nov 2006

Legal status of corpses in 1911 England

As you might expect from someone who browses at random in the library

stacks, I own several encyclopedias, which I also browse in from time

to time. You never know what you are going to find when you do

this.

I got rid of one recently. It was a 1962 Grolier's. Obviously, it was out of date, but I was using it for general reference anyway, conscious of its shortcomings. But one day I picked it up to read its article on Thurgood Marshall. It said that Marshall was an up-and-coming young lawyer, definitely someone to watch in the future. That was too much, and I gave it away.

But anyway, my main point is to talk about the legal status of corpses. One of the encyclopedias I have is a Twelfth Edition Encyclopaedia Britannica. This contains the complete text of the famous 1911 Eleventh Edition, plus three fat supplementary volumes that were released in 1920. The Britannica folks had originally planned the Twelfth Edition for around 1930, but so much big stuff happened between 1911 and 1920 that they had to do a new edition much earlier.

The Britannica is not as much fun as I hoped it would be. But there are still happy finds. Here is one such:

CORPSE (Lat. corpus, the body), a dead human body. By the common law of England a corpse is not the subject of property nor capable of holding property. It is not therefore larceny to steal a corpse, but any removal of the coffin or grave-cloths is otherwise, such remaining the property of the persons who buried the body. It is a misdemeanour to expose a naked corpse to public view. . .

(The complete article is available online.)

[ Addendum 20191213: it is a felony in California to sexually penetrate or to have sexual contact with human remains, except as authorized by law. ]

[Other articles in category /law] permanent link