Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | J |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Thu, 08 May 2025

A descriptive theory of seasons in the Mid-Atlantic

[ I started thinking about this about twenty years ago, and then writing it down in 2019, but it seems to be obsolete. I am publishing it anyway. ]

The canonical division of the year into seasons in the northern temperate zone goes something like this:

- Spring: March 21 – June 21

- Summer: June 21 – September 21

- Autumn: September 21 – December 21

- Winter: December 21 – March 21

Living in the mid-Atlantic region of the northeast U.S., I have never been happy with this. It is just not a good description of the climate.

I begin by observing that the year is not equally partitioned between the four seasons. The summer and winter are longer, and spring and autumn are brief and happy interludes in between.

I have no problem with spring beginning in the middle of March. I think that is just right. March famously comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb. The beginning of March is crappy, like February, and frequently has snowstorms and freezes. By the end of March, spring is usually skipping along, with singing birds and not just the early flowers (snowdrops, crocuses, daffodil) but many of the later ones also.

By the middle of May the spring flowers are over and the weather is getting warm, often uncomfortably so. Summer continues through the beginning of September, which is still good for swimming and lightweight clothes. In late September it finally gives way to autumn.

Autumn is jacket weather but not overcoat weather. Its last gasp is in the middle of November. By this time all the leaves have changed, and the ones that are going to fall off the trees have done so. The cool autumn mist has become a chilly winter mist. The cold winter rains begin at the end of November.

So my first cut would look something like this:

Note that this puts Thanksgiving where it belongs at the boundary between autumn (harvest season) and winter (did we harvest enough to survive?). Also, it puts the winter solstice (December 21) about one quarter of the way through the winter. This is correct. By the solstice the days have gotten short, and after that the cold starts to kick in. (“As the days begin to lengthen, the cold begins to strengthen”.) The conventional division takes the solstice as the beginning of winter, which I just find perplexing. December 1 is not the very coldest part of winter, but it certainly isn't autumn.

There is something to be said for it though. I think I can distinguish several subseasons — ten in fact:

Dominus Seasonal Calendar

Midwinter, beginning around the solstice, is when the really crappy weather arrives, day after day of bitter cold. In contrast, early and late winter are typically much milder. By late February the snow is usually starting to melt. (March, of course, is always unpredictable, and usually has one nasty practical joke hiding up its sleeve. Often, March is pleasant and springy in the second week, and then mocks you by turning back into January for the third week. This takes people by surprise almost every year and I wonder why they never seem to catch on.)

Similarly, the really hot weather is mostly confined to midsummer. Early and late summer may be warm but you do not get blazing sun and you have to fry your eggs indoors, not on the pavement.

Why the seasons seem to turn in the middle of each month, and not at the beginning, I can't say. Someone messed up, but who? Probably the Romans. I hear that the Persians and the Baha’i start their year on the vernal equinox. Smart!

Weather in other places is very different, even in the temperate zones. For example, in southern California they don't have any of the traditional seasons. They have a period of cooler damp weather in the winter months, and then instead of summer they have a period of gloomy haze from June through August.

However

I may have waited too long to publish this article, as climate change seems to have rendered it obsolete. In recent years, we have barely had midwinter, and instead of the usual two to three annual snows we have zero. Midsummer has grown from two to four months, and summer now lasts into October.

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Wed, 14 Aug 2024Benjamin Franklin wrote and published Poor Richard's Almanack annually from 1732 to 1758. Paper was expensive and printing difficult and time-consuming. The type would be inked, the sheet of paper laid on the press, the apprentices would press the sheet, by turning a big screw. Then the sheet was removed and hung up to dry. Then you can do another printing of the same page. Do this ten thousand times and you have ten thousand prints of a sheet. Do it ten thousand more to print a second sheet. Then print the second side of the first sheet ten thousand times and print the second side of the second sheet ten thousand times. Fold 20,000 sheets into eighths, cut and bind them into 10,000 thirty-two page pamphlets and you have your Almanacks.

As a youth, Franklin was apprenticed to his brother James, also a printer, in Boston. Franklin liked the work, but James drank and beat him, so he ran away to Philadelphia. When James died, Benjamin sent his widowed sister-in-law Ann five hundred copies of the Almanack to sell. When I first heard that I thought it was a mean present but I was being a twenty-first-century fool. The pressing of five hundred almanacks is no small feat of toil. Ann would have been able to sell those Almanacks in her print shop for fivepence each, or ₤10 8s. 4d. That was a lot of money in 1735.

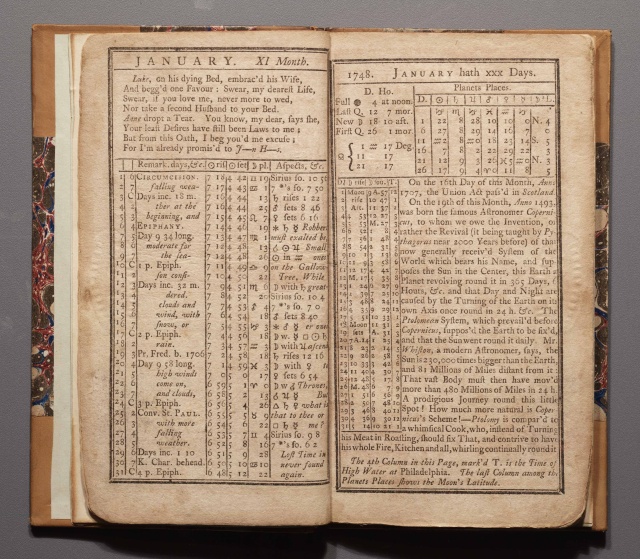

In 1748 Franklin increased the size and the price. Here's a typical page from the 1748 Almanack:

Wow, there's a lot of stuff going on there. Here's a smaller excerpt, this time from November 1753:

The leftmost column is the day of the month, and then the next column is the day of the week, with 2–7 being Monday through Saturday. Sunday is denoted with a letter “G”. I thought this was G for God, but I see that in 1748 Franklin used “C” and in 1752 he used “A”, so I don't know.

The third column combines a weather forecast and a calendar. The weather forecast is in italic type, over toward the right: “Clouds and threatens cold rains and snow” in the early part of the month. Sounds like November in Philadelphia. The roman type gives important days. For example, November 1 is All Saints Day and November 5 is the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot. November 10 is given as the birthday of King George II, then still the King of Great Britain.

The Sundays are marked with some description in the Christian liturgical calendar. For example, “20 past Trin.” means it's the start of the 20th week past Trinity Sunday.

This column also has notations like “Days dec. 4 32” and “Days dec. 5 h.” that I haven't been able to figure out. Something about the decreasing length of the day in November maybe? [ Addendum: Yes. See below. ] The notation on November 6 says “Day 10 10 long” which is consistent with the sunrise and sunset times Franklin gives for that day. The fourth and fifth columns, labeled “☉ ris” and “☉ set” are the times of sunrise and sunset, 6:55 (AM) and 5:05 (PM) respectively for November 6, ten hours and ten minutes apart as Franklin says.

“☽ pl.” is the position of the moon in the sky. (I guess “pl.” is short for “place”.) The sky is divided into twelve “houses” of 30 degrees each, and when it says that the “☽ pl.” on November 6 is “♓ 25” I think it means the moon is !!\frac{25}{30}!! of the way along in the house of Pisces on its way to the house of Aries ♈. If you look at the January 1748 page above you can see the moon making its way through the whole sky in 29 days, as it does.

The last column, “Aspects, &c.” contains more astronomy. “♂ rise 6 13” means that Mars will rise at 6:13 that day. (But in the morning or the evening?) ⚹♃♀ on the 12th says that Jupiter is in sextile aspect to Venus, which means that they are in the sky 60 degrees apart. Similarly □☉♃ means that the Sun and Jupiter are in Square aspect, 90 degrees apart in the sky.

Also mixed into that last column, taking up the otherwise empty space, are the famous wise sayings of Poor Richard. Here we see:

Serving God is Doing Good to Man,

but Praying is thought an easier Service,

and therefore more generally chosen.

Back on the January page you can see one of the more famous ones, Lost Time is never found again.

Franklin published an Almanack in 1752, the year that the British Calendar Act of 1751 updated the calendar from Julian to Gregorian reckoning. To bring the calendar into line with Gregorian, eleven days were dropped from September that year. I wondered what Franklin's calendar looked like that month. Here it is with the eleven days clearly missing:

The leftmost day-of-the-month column skips right from September 2 to September 14, as the law required. On this copy someone has added the old dates in the margin. Notice that St. Michael's Day, which would have been on Friday September 18th in the old calendar, has been moved up to September 29th. In most years Poor Richard's Almanack featured an essay by Poor Richard, little poems, and other reference material. The 1752 Almanack omitted most of this so that Franklin could use the space to instead reprint the entire text of the Calendar Act.

This page also commemorates the Great Fire of London, which began September 2, 1666.

Wikipedia tells me that Franklin may have gotten the King's birthday wrong. Franklin says November 10, but Wikipedia says November 9, and:

Over the course of George's life, two calendars were used: the Old Style Julian calendar and the New Style Gregorian calendar. Before 1700, the two calendars were 10 days apart. Hanover switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar on 19 February (O.S.) / 1 March (N.S.) 1700. Great Britain switched on 3/14 September 1752. George was born on 30 October Old Style, which was 9 November New Style, but because the calendar shifted forward a further day in 1700, the date is occasionally miscalculated as 10 November.

Ugh, calendars.

I got these scans from a web site called The Rare Book Room, but I found their user interface very troublesome, so I have scraped all the images they had. You may find them at https://pic.blog.plover.com/calendar/poor-richards-almanack/archive/. I'm pretty sure the copyright has expired, so share and enjoy.

Addenda

Several people have pointed out that the mysterious letters G, C, A on Sundays are the so-called dominical letters, used in remembering the correspondence between days of the month and days of the week, and important in the determination of the dates of Easter and other moveable feasts.

Why Franklin included them in the Almanack is not clear to me, as one of the main purposes of the almanac itself is so that you do not have to remember or calculate those things, you can just look them up in the almanac.

Mikkel Paulson explained the 'days dec.' and 'days inc.' notations: they describe the length of the day, but reported relative to the length of the most recent solstice. For example, the November 1753 excerpt for November 2 says "Days dec. 4 32". Going by the times of sunrise and sunset on that day, the day was 10 hours 18 minutes long. Adding the 4 hours 32 minutes from the notation we have 14 hours 50 minutes, which is indeed the length of the day on the summer solstice in Philadelphia, or close to it.

Similarly the notation on November 14 says "Days dec. 5 h" for a day that is 9 hours 50 minutes between sunrise and sunset, five hours shorter than on the summer solstice, and the January 3 entry says "Days inc. 18 m." for a 9h 28m day which is 18 minutes longer than the 9h 10m day one would have on the winter solstice.

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Tue, 06 Feb 2024

Jehovah's Witnesses do not number the days of the week

[ Content warning: Rambly. ]

Two Jehovah's Witnesses came to the door yesterday and at first I did not want to talk to them but as they were leaving I remembered that I had a question. I asked them what they called the days of the week. They were very puzzled by this because it turns out that they call them Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and so on, just like everyone else in this country. They were so puzzled that they did not even take the opportunity to continue the conversation. They thanked me for coming to the door, and left.

I found this interesting. The reason I had asked is that the JW religion is very strict regarding paganism. For example, they do not observe Christmas or Easter, because these holidays, to them, have a suspicious pagan origin. A few months ago I had wondered: do they celebrate Thanksgiving? I thought it was possible. As far as I know it has no pagan connection at all, and an observance of giving thanks to Jehovah seemed consistent with their beliefs. No, it turns out that they don't, on the principle that to single out one special day might lead them to neglect to give proper thanks to Jehovah on the other days.

So, I wondered, if they object to Easter, how do they feel about the days of the week? To speak of Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday is to honor the pagan Germanic gods Tyr, Odin, Thor, and Frigg, and I thought they might object to this also. The Quakers referred to the days of the week as First Day, Second Day, and so on for this reason. But the issue appears to have flown under the JWs' radar.

I didn't ask about the months, assuming that if they didn't cringe when speaking of Thor's Day, they wouldn't have a problem with the month of Janus (the two-faced god of boundaries) or with Maia (her fertility festival is in May) or with the month of the deified person of Roman Emperor Augustus.

I have a sense that Quakers are generally more sophisticated thinkers than Jehovah's Witnesses. They objected to the names of the months also, but decided it would be too confusing to change them. But they saw their opportunity in 1752, when the Kingdom of Great Britain finally brought its calendar in line with the rest of Europe. Along with the other calendrical changes, the Quakers agreed amongst themselves to start calling the months after numbers instead of the old-style names.

I had a conversation once with Larry Wall, who is himself a devout Christian. We were talking about Jehovah's Witnesses, because at that time there was a prominent member of the Perl community who was one. Larry, not at all a venomous person, said with some venom, that the JWs were “a cult”.

“A ‘cult’?” I asked. “What do you mean?” People often use the word cult as a pejorative for “sect” or religion: a cult is any religion that I don't like. But Larry, as usual, was wiser and more thoughtful than that. He said that he called them a cult because you are not allowed to leave. If you do, the other JWs, even your close friends and your family, are no longer allowed to associate with you, and if they do, they may be threatened with expulsion.

I thought that seemed like a principled definition, and it has served me since then. Sometimes, encountering other organizations from which it was difficult to extract onesself, I have heard Larry's voice in my mind, saying “that's a cult”. Thanks, Larry.

I have a draft article about how Larry Wall is my model for a rational, admirable Christian, but I'm not sure it is ever going to come together.

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Sat, 16 Oct 2021

Who is the namesake of the old Hungarian name for the month of June?

[ Previously ]

One oddity about the old-style Hungarian month names that I do not have time to investigate is that the old name of June was Szent Iván hava, Saint Ivan's month, or possibly Saint John's month. “John” in Hungarian is not Iván, it is Ján or János, at least at present. Would a Hungarian understand Szent Iván as a recognizably foreign name? I wonder which saint this is actually?

There is a Saint Ivan of Rila, but he is Bulgarian, so that could be a coincidence. Hungarian Wikipedia strangely does not seem to have an article about the most likely candidate, St. John the Evangelist, so I could not check if that John is known there as Ján or Iván or something else.

It does have an article about John the Baptist, who in Hungarian called Keresztelő János, not Iván. But that article links to the page about St. John the Baptist's Eve, which is titled Szent Iván éjszakája.

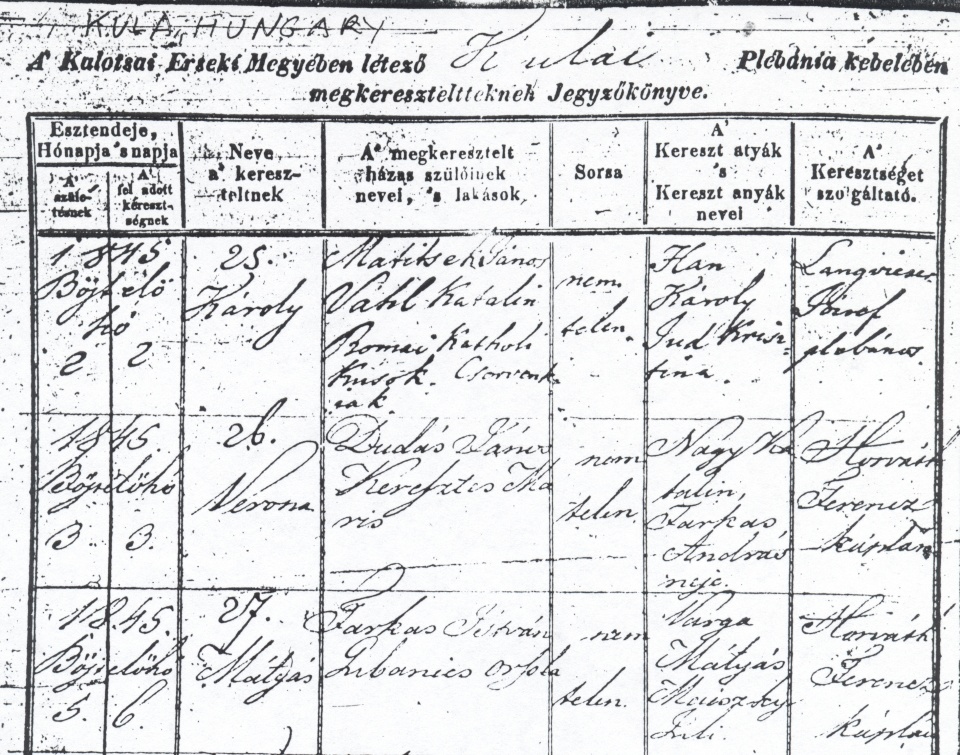

Further complicating the whole matter of Szent Iván hava is the issue that there have always been many Slavs in Hungary. The original birth record page is marked “KULA, HUNGARY”, which if correct puts it in what is now called Kula, Serbia — Hungary used to be bigger than it is now. Still why would the name of the month be in Slavic and not Magyar?

Do any of my Gentle Readers understand what is going on here?

[ Addendum: The English Wikipedia page for the Bulgarian Saint Ivan of Rila gives the Bulgarian-language version of his name. It's not written as Иван (“Ivan”) but as Йоан (“John”). The Bulgarian Wikipedia article about him is titled Иван Рилски (“Ivan Rilski”) but in the first line and the header of the infobox, his name is given instead as Йоан. I do not understand the degree to which John and Ivan are or are not interchangeable in this context. ]

[ Addendum 20211018: Michael Lugo points out that it is unlikely to be Ivan of Rila, whose feast day is in October. M. Lugo is right. This also argues strongly against the namesake of Szent Iván hava being John the Evangelist, as his feast is in December. The feast of John the Baptist is in June, so the Szent Iván of Szent Iván hava is probably John the Baptist, same as in Szent Iván éjszakája. I would still like to know why it is Szent Iván and not Szent János though. ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Fri, 15 Oct 2021I had a conversation with a co-worker about the origin of his name, in which he showed me the original Hungarian birth record of one of his ancestors. (The sample below does not include the line with that record.)

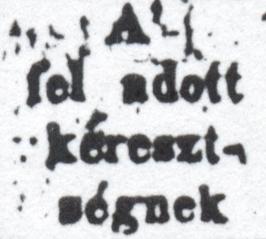

I had a fun time digging through this to figure out what it said. As you see, the scan quality is not good. The person writing the records has good handwriting, but not perfect, and not all the letters are easy to make out. (The penmanship of the second and third lines is noticeably better than the first.) Hungarian has letters ö and ő, which are different, but hard to distinguish when written longhand. The printed text is in a small font and is somewhat smudged. For example, what does this say?

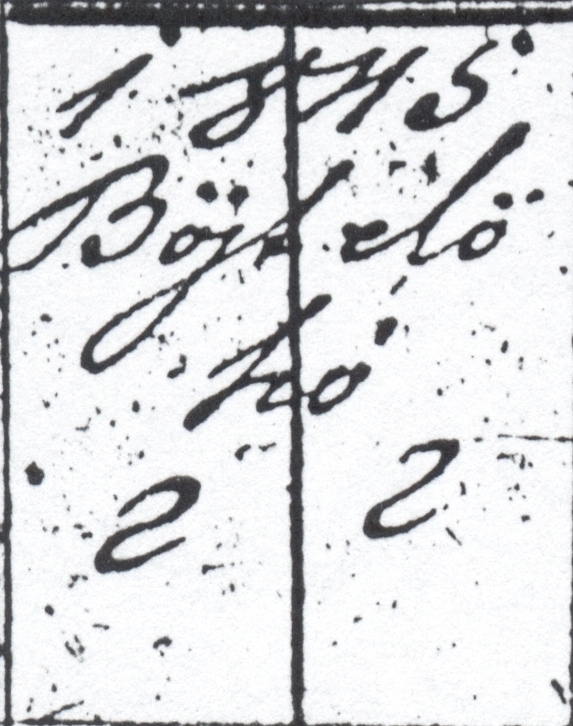

Is the first letter in the second line an ‘f’ or a long ‘s’? Is “A’” an abbreviation, and if so what for? Is that a diacritical mark over the ‘e’ in the third line, or just a smudge? Except for the last, I don't know, but kereztségnek is something about baptism, maybe a dative form or something, so that column is baptism dates. This resolves one of the puzzles, which is why there are two numbers in the two leftmost columns: one is the birth date and one is the baptism date, and sometimes the baptism was done on a different day. For example, in the third line the child Mátyás (“Matthew”) was born on the 5th, and baptized on the 6th.

But the 6th of what? The box says “1845 / something” and presumably the something is the name of the month.

But I couldn't quite make it out (Bójkeló kó maybe?) and Google did not find anything to match my several tries. No problem, I can go the other direction: just pull up a list of the names of the months in Hungarian and see which one matches.

That didn't work. The names of the months in Hungarian are pretty much the same as in English (január, február, etc.) and there is nothing like Bójkeló kó. I was stuck.

But then I had a brainwave and asked Google for “old hungarian month names”. Paydirt! In former times, the month of February was called böjt elő hava, (“the month before fast”; hava is “month”) which here is abbreviated to Böjt elő ha’.

So that's what I learned: sometime between 1845 and now, the Hungarians changed the names of the months.

This page at fromhungarywithlove says that these month names were used from the 16th century until “the first third of the 20th century”.

[ Addendum 20211016: A further puzzle: The old name for June was “St. Iván's month”. Who was St. Iván? ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Tue, 21 Jun 2016

The Greek clock

In former times, the day was divided into twenty-four hours, but they

were not of equal length. During the day, an hour was one-twelfth of

the time from sunrise to sunset; during the night, it was one-twelfth

of the time from sunset to sunrise. So the daytime hours were all

equal, and the nighttime hours were all equal, but the daytime hours

were not equal to the nighttime hours, except on the equinoxes, or at

the equator. In the summer, the day hours were longer and the night

hours shorter, and in the winter, vice versa.

Some years ago I suggested, as part of the Perl Quiz of the Week, that people write a greektime program that printed out the time according to a clock that divided the hours in this way. You can, of course, spend a lot of time and effort downloading and installing CPAN astronomical modules to calculate the time of sunrise and sunset, and reading manuals and doing a whole lot of stuff. But if you are content with approximate times, you can use some delightful shortcuts.

First, let's establish what the problem is. We're going to take the conventional time labels ("12:35" and so forth) and adjust them so that half of them take up the time from sunrise to sunset and the other half go from sunset to sunrise. Some will be stretched, and some squeezed. 01:00 in this new system will no longer mean "3600 seconds after midnight", but rather "exactly 7/12 of the way between sunset and sunrise".

To do this, we'll introduce a new daily calendar with the following labels:

| Midnight | Sunrise | Noon | Sunset | Midnight |

| 00:00 | 06:00 | 12:00 | 18:00 | 24:00 |

We'll assume that noon (when the sun is directly overhead) occurs at 12:00 and that midnight occurs at 00:00. (Or 24:00, which is the same thing.) This is pretty close to the truth anyway, although it is screwed up by such oddities as time zones and the like.

On the equinoxes, the sun rises around 06:00 and sets around 18:00, again ignoring time zones and the like. (If you live at the edge of a time zone, especially a large one like U.S. Central Time, local civil noon does not occur at solar noon, so these calculations require adjustments.) On the equinoxes the normal calendar corresponds to the Greek one, because the day and the night are each exactly twelve standard hours long. (The day from 06:00 to 18:00, and the night from 18:00 to 06:00 the following day.) In the winter, the sun rises later and sets earlier; in the summer it rises earlier and sets later. So let's take 06:00 to be the label for the time of sunrise in the Greek clock all year round; 18:00 is similarly the time of sunset in the Greek clock all year round.

With these conventions, it turns out that it's rather easy to calculate the approximate time of sunrise for any day of the year. You need two magic numbers, A and d. The number d is the number of days that have elapsed since the vernal equinox, which is around 19 March (or 19 September, if you live in the southern hemisphere.) The number A is a bit trickier, and I will return to it shortly.

Once you have the two numbers, you just plug into the formula:

$$\text{Sunrise} = \text{06:00} - A \sin {2\pi d\over 365.2422}$$

The tricky part is the magic number A; it depends on your latitude. At the equator, it is 0. And you can probably calculate it directly from the latitude, if you happen to know your latitude. I do know my latitude (Philadelphia is conveniently located at almost exactly 40° N) but I failed observational astronomy classes twice, so I don't know how to do the necessary calculation.(Actually it occurs to me now that !!A = 360 \text{ min}\times (1-\cos L)!!, should work, where L is the absolute latitude. For the equator (!!L = 90^\circ!!), this gives 0, as it should, and for Philadelphia it gives !!360\text{ min}\cdot (1- \cos 40^\circ) \approx 84.22\text{ min}!!, which is just about right.)

However, there's another trick you can use even if you don't know your latitude. If you know the time of sunset on the summer solstice, you can calculate A quite easily:

$$A = {\text{ Sunset on summer solstice}} - \text{18:00}$$

Does that really help? If it were October, it might not. But the summer solstice is today. So all you have to do is to look out the window in the evening and notice when the sun seems to be going down. Then plug the time into the formula. (Or you can remember what happened yesterday, or wait until tomorrow; the time of sunset hardly changes at all this time of year, by only a few seconds per day. Or you could look at the front page of a daily newspaper, which will also tell you the time of sunset.)

The sun went down here around 20:30 today, but that is really 19:30

because of

daylight

saving time, so we get A = 19:30 -

18:00 = 90 minutes, which happily agrees with the 84.22 we got earlier by a

different method. Then the time of sunrise in Philadelphia d

days after the vernal equinox is

$$\text{Sunrise} =

\text{06:00} - 90\text{ min}\cdot \sin {2\pi d\over 365.2422}$$

Today is June 21, which is (counts on fingers) about 31+30+31 = 92

days after the vernal equinox which was around March 21. So notice

that the formula above involves !!\sin{2\pi\cdot 92\over 365.2422}

\approx \sin{\frac\pi 2} = 1!! because 92 is just about one-fourth of

365.2422—that is, today is just about a quarter of a year after the

vernal equinox. So the formula says that sunrise ought to be about

04:30, or, because of

daylight

saving time, so we get A = 19:30 -

18:00 = 90 minutes, which happily agrees with the 84.22 we got earlier by a

different method. Then the time of sunrise in Philadelphia d

days after the vernal equinox is

$$\text{Sunrise} =

\text{06:00} - 90\text{ min}\cdot \sin {2\pi d\over 365.2422}$$

Today is June 21, which is (counts on fingers) about 31+30+31 = 92

days after the vernal equinox which was around March 21. So notice

that the formula above involves !!\sin{2\pi\cdot 92\over 365.2422}

\approx \sin{\frac\pi 2} = 1!! because 92 is just about one-fourth of

365.2422—that is, today is just about a quarter of a year after the

vernal equinox. So the formula says that sunrise ought to be about

04:30, or, because of  daylight saving time, that's 05:30 local civil time. This time of

year the night is only 9 standard hours long, so the Greek nighttime

hour is !!\frac9{12}!! standard hours long, or 45 minutes. Right now

it's 22:43 daylight time, which is 133 standard minutes past sundown,

or just about 3 Greek nighttime hours. So the Greek time is close to

9 PM. In another 2:15 standard hours another 3 Greek hours will have

elapsed and it will be Greek midnight; this coincides with standard

midnight, which is 01:00 local civil time because of

daylight saving time, that's 05:30 local civil time. This time of

year the night is only 9 standard hours long, so the Greek nighttime

hour is !!\frac9{12}!! standard hours long, or 45 minutes. Right now

it's 22:43 daylight time, which is 133 standard minutes past sundown,

or just about 3 Greek nighttime hours. So the Greek time is close to

9 PM. In another 2:15 standard hours another 3 Greek hours will have

elapsed and it will be Greek midnight; this coincides with standard

midnight, which is 01:00 local civil time because of  daylight saving.

daylight saving.

Here's code for greektime that you can run where you to find out the current Greek time. I hereby place this program in the public domain.

#!/usr/bin/perl

#

# Calculate local time in fictitious Greek clock

# http://blog.plover.com/calendar/Greek-clock.html

# Author: Mark Jason Dominus (mjd@plover.com)

# This program is in the public domain.

#

my $PI = atan2(0, -1);

use Getopt::Std;

my %opt;

getopts('l:s:', \%opt) or usage();

my $A;

if ($opt{l} =~ /\d/) {

$A = 360 * 60 * (1-cos(radians($opt{l})));

} elsif ($opt{s} =~ /:/) {

my ($hr, $mn) = split /:/, $opt{s};

$A = (($hr - 18) * 60 + $mn) * 60;

} else {

usage();

}

my $time = time;

my $days_since_equinox = ($time - 1047950185)/86400;

my $days_per_year = 365.2422;

my $sunrise_adj = $A * sin($days_since_equinox / $days_per_year

* 2 * $PI );

my $length_of_daytime = 12 * 3600 + 2 * $sunrise_adj;

my $length_of_nighttime = 12 * 3600 - 2 * $sunrise_adj;

my $time_of_sunrise = 6 * 3600 - $sunrise_adj;

my $time_of_sunset = 18 * 3600 + $sunrise_adj;

my ($gh, $gm) = time_to_greek($time);

my ($h, $m) = (localtime($time))[2,1];

printf "Standard: %2d:%02d\n", $h, $m;

printf " Greek: %2d:%02d\n", $gh, $gm;

sub time_to_greek {

my ($epoch_time) = shift;

my $time_of_day;

{ my ($h, $m, $s, $dst) = (localtime($epoch_time))[2,1,0,8];

$time_of_day = ($h-$dst) * 3600 + $m * 60 + $s;

}

my ($greek, $hour, $min);

if ($time_of_day < $time_of_sunrise) {

# change early morning into night

$time_of_day += 24 * 3600;

}

if ($time_of_day < $time_of_sunset) {

# day

my $diff = $time_of_day - $time_of_sunrise;

$greek = 6 + ($diff / $length_of_daytime) * 12;

} else {

# night

my $diff = $time_of_day - $time_of_sunset;

$greek = 18 + ($diff / $length_of_nighttime) * 12;

}

$hour = int($greek);

$min = int(60 * ($greek - $hour));

($hour, $min);

}

sub radians {

my ($deg) = @_;

return $deg * 2 * $PI / 360;

}

sub usage {

print STDERR "Usage: greektime [ -l latitude ] [ -s summer_solstice_sunset ]

One of latitude or sunset time must be given.

Latitude should be in degrees north of the equator.

(Negative for southern hemisphere)

Sunset time should be given in the form '19:37' in local STANDARD time.

(Southern hemisphere should use the WINTER solstice.)

";

exit 2;

}

This article has been in the works since January of 2007, but I missed

the deadline on 18 consecutive solstices. The 19th time is the

charm![ Addendum 20160711: Sean Santos has some corrections to my formula for A. ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Wed, 04 Jan 2012

Mental astronomical calculations

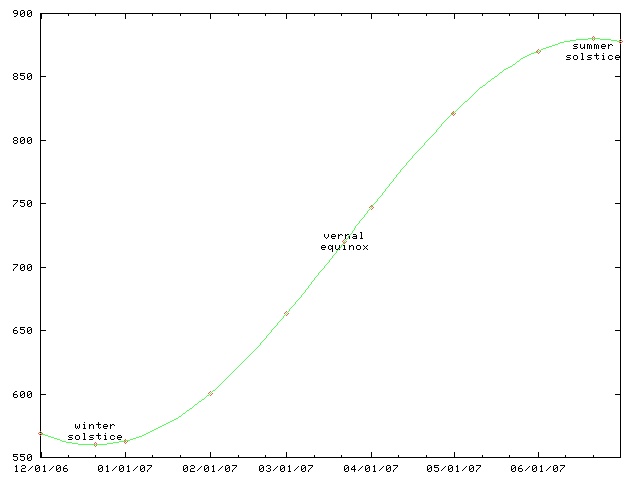

As you can see from the following graph, the daylight length starts

increasing after the winter solstice (last week) but it does so quite

slowly at first, picking up speed, and reaching a maximum rate of

increase at the vernal equinox.

The day length is given by a sinusoid with amplitude that depends on your latitude (and also on the axial tilt of the Earth, which is a constant that we can disregard for this problem.) That is, it is a function of the form a + k sin 2πt/p, where a is the average day length (12 hours), k is the amplitude, p is the period, which is exactly one year, and t is amount of time since the vernal equinox. For Philadelphia, where I live, k is pretty close to 3 hours because the shortest day is about 3 hours shorter than average, and the longest day is about 3 hours longer than average. So we have:

day length = 12 hours + 3 hours · sin(2πt / 1 year)Now let's compute the rate of change on the equinox. The derivative of the day length function is:

rate of change = 3h · (2π / 1y) · cos(2πt / 1y)At the vernal equinox, t=0, and cos(…) = 1, so we have simply:

rate of change = 6πh / 1 year = 18.9 h / 365.25 daysThe numerator and the denominator match pretty well. If you're in a hurry, you might say "Well, 360 = 18·20, so 365.25 / 18.9 is probably about 20," and you would be right. If you're in slightly less of a hurry, you might say "Well, 361 = 192, so 365.25 / 18.9 is pretty close to 19, maybe around 19.2." Then you'd be even righter.

So the change in day length around the equinox (in Philadelphia) is around 1/20 or 1/19 of an hour per day—three minutes, in other words.

The exact answer, which I just looked up, is 2m38s. Not too bad. Most of the error came from my estimation of k as 3h. I guessed that the sun had been going down around 4:30, as indeed it had—it had been going down around 4:40, so the correct value is not 3h but only 2h40m. Had I used the correct k, my final result would have been within a couple of seconds of the right answer.

Exercise: The full moon appears about the same size as a U.S. quarter (1 inch diameter circle) held nine feet away (!) and also the same size as the sun, as demonstrated by solar eclipses. The moon is a quarter million miles away and the sun is 93 million miles away. What is the actual diameter of the sun?

[ Addendum 20120104: An earlier version of this article falsely claimed that the full moon appears the same size as a quarter held at arm's length. This was a momentary brain fart, not a calculational error. Thanks to Eric Roode for pointing out this mistake. ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Fri, 27 May 2011

Watch out for the Calendar Geeks

Yesterday on the private IRC server run by my employer, one of my

co-workers said:

<MHO> [My wife] just informed me that this year, July has five Fridays, five Saturdays and five Sundays. This only happens every 800 or so years.He made the mistake of invoking the Calendar Geeks, so here I am, ready to assist!<MHO> Calendar geeks, rejoice!

First, I note that any weird calendar event that occurs, will recur in no more than 400 years, because the Gregorian calendar repeats in a 400-year cycle and 400 Gregorian years is also an exact multiple of 7 days. (It is 400·365 days + (100 - 4 + 1) leap days = 146,097 days, which is exactly 20,871 weeks.) So it is impossible that the event could be as rare as once every 800 or so years. If it happens in 2011, then it happened in 1611 (in Catholic countries) and it will happen in 2411 also.

Now in the particular case cited by MHO, it's clear that since the length of July doesn't vary, the number of Fridays, Saturdays or Sundays depends only on the day of the week on which July 1 falls. You get five Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays whenever July 1 falls on a Friday. Common sense suggests that this should happen about 1/7 of the time, and so around every 7 years, not every 800, or even every 400 years. And in fact it last occurred in 2005, and will occur next in 2016.

[ Addendum 20110527: It turns out this is actually a Thing; there is even a Snopes page about it. People will tweet almost anything, it seems. ]

[ Addendum 20110701: Matt Parker posted an extensive article about why he found this particular non-fact so dismaying. ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Fri, 29 Feb 2008

Happy Leap Day! Persian edition

Roland Young has brought to my attention that the

Persian calendar uses a hybrid 7/29 and 8/33 system. I was going to

post this as an addendum to today's Leap Day article, but

it got too long.

If I understand the rules correctly, to determine if a Persian year is a leap year, one applies the following algorithm to the Persian year number y. (Note that the current Persian year is not 2008, but 1386. Persian year 1387 will begin on the vernal equinox.) I will write a % b to denote the remainder when a is divided by b. Then:

- Let a = (y + 2345) % 2820.

- If a is 2819, y is a leap year. Otherwise,

- Let b = a % 128.

- If b < 29, let c = b. Otherwise, let c = (b - 29) % 33.

- If c = 0, y is not a leap year. Otherwise,

- If c is a multiple of 4, y is a leap year. Otherwise,

- y is not a leap year.

This produces 683 leap years out of every 2820, which means that the average calendar year is 365.24219858 days.

How does this compare with the Dominus calendar? It is indeed more accurate, but I consider 683/2820 to be an unnecessarily precise representation of the vernal equinox year, especially inasmuch as the length of the year is changing. And the rule, as you see, is horrendous, requiring either a 2,820-entry lookup table or complicated logic.

Moreover, the Persian and Gregorian calendar are out of sync at present. Persian year 1387, which begins next month on the vernal equinox, is a leap year. But the intercalation will not take place until the last day of the year, around 21 March 2009. The two calendars will not sync up until the year 2092/1470, and then will be confounded only eight years later by the Gregorian 100-year exception. After that they will agree until 2124/1502. Clearly, even if it were advisable to switch to the Persian calendar, the time is not yet right.

I found this Frequently Asked Questions About Calendars page extremely helpful in preparing this article. The Wikipedia article was also useful. Thanks again to Roland Young for bringing this matter to my attention.

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Happy Leap Day!

I have an instructive followup to yesterday's article all ready to

go, analyzing a technique for finding rational roots of polynomials

that I found in the First Edition of the Encyclopædia

Britannica. A typically Universe-of-Discourse kind of

article. But I'm postponing it to next month so that I can bring you

this timely update.

Everyone knows that our calendar periodically contains an extra day, known to calendar buffs as an "intercalary day", to help make it line up with the seasons, and that this intercalary day is inserted at the end of February. But, depending on how you interpret it, this isn't so. The extra day is actually inserted between February 23 and February 24, and the rest of February has to move down to make room.

I will explain. In Rome, 23 February was a holiday called Terminalia, sacred to Terminus, the god of boundary markers. Under the calendars of the Roman Republic, used up until 46 BCE, an intercalary month, Mercedonius, was inserted into the calendar from time to time. In these years, February was cut down to 23 days (and good riddance; nobody likes February anyway) and Mercedonius was inserted at the end.

When Julius Caesar reformed the calendar in 46, he specified that there would be a single intercalary day every four years much as we have today. As in the old calendar, the intercalary day was inserted after Terminalia, although February was no longer truncated.

So the extra day is actually 24 February, not 29 February. Or not. Depends on how you look at it.

Scheduling intercalary days is an interesting matter. The essential problem is that the tropical year, which is the length of time from one vernal equinox to the next, is not an exact multiple of one day. Rather, it is about 365¼ days. So the vernal equinox moves relative to the calendar date unless you do something to fix it. If the tropical year were exactly 365¼ days long, then four tropical years would be exactly 1461 days long, and it would suffice to make four calendar years 1461 days long, to match. This can be accomplished by extending the 365-day calendar year with one intercalary day every four years. This is the Julian system.

Unfortunately, the tropical year is not exactly 365¼ days long. It is closer to 365.24219 days long. So how many intercalary days are needed?

It suffices to make 100,000 calendar years total exactly 36,524,219 days, which can be accomplished by adding a day to 24,219 years out of every 100,000. But this requires a table with 100,000 entries, which is too complicated.

We would like to find a system that requires a simpler table, but which is still reasonably accurate. The Julian system requires a table with 4 entries, but gives a calendar year that averages 365.25 days long, which is 0.00781 too many. Since this is about 1/128 day, the Julian calendar "gains a day" every 128 years or so, which means that the vernal equinox slips a day earlier every 128 years, and eventually the daffodils and crocuses are blooming in January.

Not everyone considers this a problem. The Islamic calendar is only 355 days long, and so "loses" 10 days per year, which means that after 18 years the Islamic new year has moved half a year relative to the seasons. The annual Islamic holy month of Ramadan coincided with July-August in 1980 and with January-February in 1997. The Muslims do intercalate, but they do it to keep the months in line with the phases of the moon.

Still, supposing that we do consider this a problem, we would like to find an intercalation scheme that is simple and accurate. This is exactly the problem of finding a simple rational approximation to 0.24219. If p/q is close to 0.24219, then one can introduce p intercalary days every q years, and q is the size of the table required. The Julian calendar takes p/q = 1/4 = 0.25, for an error around 1/128. The Gregorian calendar takes p/q = 97/400 = 0.2425, for an error of around 1/3226. Again, this means that the Gregorian calendar gains a day on the seasons every 3,226 years or so. Can we do better?

Any time the question is "find a simple rational approximation to a number" the answer is likely to involve continued fractions. 365.24219 is equal to:

$$ 365 + {1\over \displaystyle 4 + {\strut 1\over\displaystyle 7 + {\strut 1\over\displaystyle 1 + {\strut 1\over\displaystyle 3 + {\strut 1\over\displaystyle 24 + {\strut 1\over\displaystyle 6 + \cdots }}}}}}$$

which for obvious reasons, mathematicians abbreviate to [365; 4, 7, 1, 3, 24, 6, 2, 2]. This value is exact. (I had to truncate the display above because of a bug in my TeX formula tool: the full fraction goes off the edge of the A0-size page I use as a rendering area.)As I have mentioned before, the reason this horrendous expression is interesting is that if you truncate it at various points, the values you get are the "continuants", which are exactly the best possible rational approximations to the original number. For example, if we truncate it to [365], we get 365, which is the best possible integer approximation to 365.24219. If we truncate it to [365; 4], we get 365¼, which is the Julian calendar's approximation.

Truncating at the next place gives us [365; 4, 7], which is 365 + 1/(4 + 1/7) = 356 + 1/(29/7) = 365 + 7/29. In this calendar we would have 7 intercalary days out of 29, for a calendar year of 365.241379 days on average. This calendar loses one day every 1,234 years.

The next convergent is [365; 4, 7, 1] = 8/33, which requires 8 intercalary days every 33 years for an average calendar year of 0.242424 days. This schedule gains only one day in 4,269 years and so is actually more accurate than the Gregorian calendar currently in use, while requiring a table with only 33 entries instead of 400.

The real question, however, is not whether the table can be made smaller but whether the rule can be made simpler. The rule for the Gregorian calendar requires second-order corrections:

- If the year is a multiple of 400, it is a leap year; otherwise

- If the year is a multiple of 100, it is not a leap year; otherwise

- If the year is a multiple of 4, it is a leap year.

And one frequently sees computer programs that omit one or both of the exceptions in the rule.

The 8/33 calendar requires dividing by 33, which is its most serious problem. But it can be phrased like this:

- Divide the year by 33. If the result is 0, it is not a leap year. Otherwise,

- If the result is divisible by 4, it is a leap year.

Furthermore, the rule as I gave it above has another benefit: it matches the Gregorian calendar this year and will continue to do so for several years. This was more compelling when I first proposed this calendar back in 1998, because it would have made the transition to the new calendar quite smooth. It doesn't matter which calendar you use until 2016, which is a leap year in the Gregorian calendar but not in the 8/33 calendar as described above. I may as well mention that I have modestly named this calendar the Dominus calendar.

But time is running out for the smooth transition. If we want to get the benefits of the Dominus calendar we have to do it soon. Help spread the word!

[ Pre-publication addendum: Wikipedia informs me that it is not correct to use the tropical year, since this is not in fact the time between vernal equinoxes, owing to the effects of precession and nutation. Rather, one should use the so-called vernal equinox year, which is around 365.2422 days long. The continued fraction for 365.2422 is slightly different from that of 356.24219, but its first few convergents are the same, and all the rest of the analysis in the article holds the same for both years. ]

[ Addendum 20080229: The Persian calendar uses a hybrid 7/29 and 8/33 system. Read all about it. ]

[ Addendum 20240229: Alas, the clock has run out on my attempt to get the world to adopt the Dominus calendar. ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Tue, 24 Jan 2006

Franklin and Daylight Saving Time

You often hear it asserted that Benjamin Franklin was the inventor of

daylight saving time. But it's really not true.

The essential feature of DST is that there is an official change to the civil calendar to move back all the real times by one hour. Events that were scheduled to occur at noon now occur at 11 AM, because all the clocks say noon when it's really 11 AM.

The proposal by Franklin that's cited as evidence that he invented DST doesn't propose any such thing. It's a letter to the editors of The Journal of Paris, originally sent in 1784. There are two things you should know about this letter: First, it's obviously a joke. And second, what it actually proposes is just that people should get up earlier!

I went home, and to bed, three or four hours after midnight. . . . An accidental sudden noise waked me about six in the morning, when I was surprised to find my room filled with light. . . I got up and looked out to see what might be the occasion of it, when I saw the sun just rising above the horizon, from whence he poured his rays plentifully into my chamber. . .Franklin then follows with a calculation of the number of candles that would be saved if everyone in Paris got up at six in the morning instead of at noon, and how much money would be saved thereby. He then proposes four measures to encourage this: that windows be taxed if they have shutters; that "guards be placed in the shops of the wax and tallow chandlers, and no family be permitted to be supplied with more than one pound of candles per week", that travelling by coach after sundown be forbidden, and that church bells be rung and cannon fired in the street every day at dawn.. . . still thinking it something extraordinary that the sun should rise so early, I looked into the almanac, where I found it to be the hour given for his rising on that day. . . . Your readers, who with me have never seen any signs of sunshine before noon, and seldom regard the astronomical part of the almanac, will be as much astonished as I was, when they hear of his rising so early; and especially when I assure them, that he gives light as soon as he rises. I am convinced of this. I am certain of my fact. One cannot be more certain of any fact. I saw it with my own eyes. And, having repeated this observation the three following mornings, I found always precisely the same result.

I considered that, if I had not been awakened so early in the morning, I should have slept six hours longer by the light of the sun, and in exchange have lived six hours the following night by candle-light; and, the latter being a much more expensive light than the former, my love of economy induced me to muster up what little arithmetic I was master of, and to make some calculations. . .

Franklin finishes by offering his brilliant insight to the world free of charge or reward:

I expect only to have the honour of it. And yet I know there are little, envious minds, who will, as usual, deny me this and say, that my invention was known to the ancients, and perhaps they may bring passages out of the old books in proof of it. I will not dispute with these people, that the ancients knew not the sun would rise at certain hours; they possibly had, as we have, almanacs that predicted it; but it does not follow thence, that they knew he gave light as soon as he rose. This is what I claim as my discovery.As usual, the complete text is available online.

OK, I'm not done yet. I think the story of how I happened to find this out might be instructive.

I used to live at 9th and Pine streets, across from Pennsylvania Hospital. (It's the oldest hospital in the U.S.) Sometimes I would get tired of working at home and would go across the street to the hospital to read or think. Hospitals in general are good for that: they are well-equipped with lounges, waiting rooms, comfortable chairs, sofas, coffee carts, cafeterias, and bathrooms. They are open around the clock. The staff do not check at the door to make sure that you actually have business there. Most of the people who work in the hospital are too busy to notice if you have been hanging around for hours on end, and if they do notice they will not think it is unusual; people do that all the time. A hospital is a great place to work unmolested.

Pennsylvania Hospital is an unusually pleasant hospital. The original building is still standing, and you can go see the cornerstone that was laid in 1755 by Franklin himself. It has a beautful flower garden, with azaleas and wisteria, and a medicinal herb garden. Inside, the building is decorated with exhibits of art and urban archaeology, including a fire engine that the hospital acquired in 1780, and a massive painting of Christ healing the sick, originally painted by Benjamin West so that the hospital could raise funds by charging people a fee to come look at it. You can visit the 19th-century surgical amphitheatre, with its observation gallery. Even the food in the cafeteria is way above average. (I realize that that is not saying much, since it is, after all, a hospital cafeteria. But it was sufficiently palatable to induce me to eat lunch there from time to time.)

Having found so many reasons to like Pennsylvania Hospital, I went to visit their web site to see what else I could find out. I discovered that the hospital's clinical library, adjacent to the surgical amphitheatre, was open to the public. So I went to visit a few times and browsed the stacks.

Mostly, as you would expect, they had a lot of medical texts. But on one of these visits I happened to notice a copy of Ingenious Dr. Franklin: Selected Scientific Letters of Benjamin Franklin on the shelf. This caught my interest, so I sat down with it. It contained all sorts of good stuff, including Franklin's letter on "Daylight Saving". Here is the table of contents:

PrefaceI'm sure that anyone who bothers to read my blog would find at least some of those items appealing. I certainly did.

The Ingenious Dr. Franklin

Daylight Saving

Treatment for Gout

Cold Air Bath

Electrical Treatment for Paralysis

Lead Poisoning

Rules of Health and Long Life

The Art of Procuring Pleasant Dreams

Learning to Swim

On Swimming

Choosing Eye-Glasses

Bifocals

Lightning Rods

Advantage of Pointed Conductors

Pennsylvanian Fireplaces

Slaughtering by Electricity

Canal Transportation

Indian Corn

The Armonica

First Hydrogen Balloon

A Hot-Air Balloon

First Aerial Voyage by Man

Second Aerial Voyage by Man

A Prophecy on Aerial Navigation

Magic Squares

Early Electrical Experiments

Electrical Experiments

The Kite

The Course and Effect of Lightning

Character of Clouds

Musical Sounds

Locating the Gulf Stream

Charting the Gulf Stream

Depth of Water and Speed of Boats

Distillation of Salt Water

Behavior of Oil on Water

Earliest Account of Marsh Gas

Smallpox and Cancer

Restoration of Life by Sun Rays

Cause of Colds

Definition of a Cold

Heat and Cold

Cold by Evaporation

On Springs

Tides and Rivers

Direction of Rivers

Salt and Salt Water

Origin of Northeast Storms

Effect of Oil on Water

Spouts and Whirlwinds

Sun Spots

Conductors and Non-Conductors

Queries on Electricity

Magnetism and the Theory of the Earth

Nature of Lightning

Sound

Prehistoric Animals of the Ohio

Toads Found in Stone

Checklist of Letters and Papers

List of Correspondents

List of a Few Additional Letters

Anyway, the moral of the story, as I see it, is: If you make your way into strange libraries and browse through the stacks, sometimes you find some good stuff, so go do that once in a while.

[ Addendum 20181026: The Franklin Institute agrees. ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Fri, 20 Jan 2006

Franklin is indeed 300 years old

I can now happily report that

my

determination that Benjamin Franklin is only 299 years

old this year was mistaken. To my relief, Franklin is really 300

years old after all.

After hearing an alternative analysis from Corprew Reed, I double-checked with Daniel K. Richter, a Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania, and director of the new McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

Richter confirms Reed's analysis: By the 18th century, nearly everyone was reckoning years to start on 1 January except certain official legal documents. The official change of New Year's day was only to bring the legal documents into conformance with what everyone was already doing. So when Franklin's birthdate is reported as 6 January 1706, it means 1706 according to modern reckoning (that is, January 300 years ago) and not 1706 in the "official" reckoning (which would have been only 299 years ago).

Deke Kassabian also wrote in with a helpful reference, referring me to an article that appeared Wednesday in Slate. The relevant part says:

. . . according to documents from Boston's city registrar, he actually came into the world on the old-style Jan. 6, 1705. So, this year's tricentennial is right on time.So the matter is cleared up, and in the best possible way. Many thanks to Deke, Corprew, and Professor Richter.

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Thu, 19 Jan 2006

Franklin is probably 300 years old after all

In a

recent post, I surmised that Benjamin Franklin is only 299 years

old this year, not 300, because of rejiggering of the start of the

calendar year in England and its colonies in 1751/1752.

However, Corprew Reed writes to suggest that I am mistaken. Reed points out that although the legal start of the year prior to 1752 was 25 March, the common usage was to cite 1 January as the start of the year. The the British Calendar Act of 1751 even says as much:

WHEREAS the legal Supputation of the Year . . . according to which the Year beginneth on the 25th Day of March, hath been found by Experience to be attended with divers Inconveniencies, . . . as it differs . . . from the common Usage throughout the whole Kingdom. . .So Reed suggests that when Franklin (and others) report his birthdate as being 6 January 1706, they are referring to "common usage", the winter of the official, legal year 1705, and thus that Franklin really was born exactly 300 years ago as of Tuesday.

If so, this would be a great relief to me. It was really bothering me that everyone might be celebrating Franklin's 300th birthday a year early without realizing it.

I'm going to try to see who here at Penn I can bother about it to find out for sure one way or the other. Thanks for the suggestion, Corprew!

[ Addendum: Yes. ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Wed, 18 Jan 2006

Why 3–13 September?

In an

earlier post about the British adjustment from the Julian to the

Gregorian calendar, I pointed out that the calendar dates were

synchronized with those in use in the rest of Europe by the deletion

of 3 September through 13 September, so that Wednesday, 2 September

1752 was followed immediately by Thursday, 14 September 1752. I asked:

Why September 3-13? I don't know, although I would love to find out.Clinton Pierce has provided information which, if true, is probably the answer:

The reason for deleting the 3rd - 13th of September is that in that span there are no significant Holy Days on the Anglican calendar (at least that I can tell). September 8th's "Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary" is actually an alternate to August 14th. It's also one of the few places on the 1752 calendar where this empty span occurs beginning at midweek.If I have time, I will try to dig up an authoritative ecclesiastical calendar for 1752. The ones I have found online show several other similar gaps; for example, it seems that 12 January could have been followed by 24 January, or 14 June followed by 26 June. But these calendars may not be historically accurate — that is, they may simply be anachronistically projecting the current practices back to 1752.This would also allow the autumnal equinox (one of the significant events mentioned in the Act) to fall properly on the 21st of September whereas doing the adjustment in October (the other late 1752 span of no Holy Days) wouldn't permit that.

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link

Tue, 17 Jan 2006

An adjustment to Franklin's birthday

Thanks to the wonders of the Internet, the

text of the British Calendar Act of 1751 is available. (Should

you read the Act, it may be helpful to know that the obscure word

"supputation" just means "calculation".) This is the act that

adjusted the calendar from Julian to Gregorian and fixed the 11-day

discrepancy that had accumulated since the Nicean Council in 325 CE,

by deleting September 3-13, so that the month of September 1752 had

only 19 days:

| September 1752 | ||||||

| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

| 1 | 2 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

And why September? Had I been writing the Act, I think I would have preferred to delete a chunk of February; nobody likes February anyway.

Anyway, the effect of this was to make the year 1752 only 355 days long, instead of the usual 366.

I hadn't remembered, however, that this act was also the one that moved the beginning of the year from 25 March to 1 January. Since 1752 was the first civil year to begin on 1 January, that meant that 1751 was only 282 days long, running from 25 March through 31 December. I used to think that the authors of the Unix cal program were very clever for getting September 1752 correct:

% cal 1752

1752

January February March

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 29 30 31

April May June

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6

5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30

31

July August September

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 1 1 2 14 15 16

5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29

30 31

October November December

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 1 2

8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

31

But now I realize that they weren't clever enough to get 1751

right too:

% cal 1751

1751

January February March

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 1 2 1 2

6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

31

April May June

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 1

7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

28 29 30 26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29

30

July August September

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30

October November December

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 29 30 31

This is quite wrong, since 1751 started on March 25, and there was no

such thing as January 1751 or February 1751. When you excise eleven days from the calendar, you have a lot of puzzles. For any event that was previously scheduled to occur on or after 14 September, 1752, you now need to ask the question: should you leave its nominal date unchanged, so that the event actually occurs 11 days sooner than it would have, or do you advance its nominal date 11 days forward? The Calendar Act deals with this in some detail. Certain court dates and ecclesiastical feasts, including corporate elections, are moved forward by 11 real days, so that their nominal dates remain the same; other events are adjusted so that the occur at the same real times as they would have without the tamperings of the calendar act. Private functions are not addressed; I suppose the details were left up to the convenience of the participants.

Historians of that period have to suffer all sorts of annoyances in dealing with the dates, since, for example, you find English accounts of the Battle of Gravelines occurring on 28 July, but Spanish accounts that their Armada wasn't even in sight of Cornwall until 29 July. Sometimes the histories will use a notation like "11/21 July" to mean that it was the day known as 11 July in England and 21 July in Spain. I find this clear, but the historians mostly seem to hate this notation. ("Fractions! If I wanted to deal in fractions, I would have become a grocer, not a historian!")

You sometimes hear that there were riots by tenants, angry to be paying a full month's rent for only 19 days of tenancy in September 1752. I think this is a myth. The act says quite clearly:

. . . nothing in this present Act contained shall extend, or be construed to extend, to accelerate or anticipate the Time of Payment of any Rent or Rents, Annuity or Annuities, or Sum or Sums of Money whatsoever. . . or the Time of doing any Matter or Thing directed or required by any such Act or Acts of Parliament to be done in relation thereto; or to accelerate the Payment of, or increase the Interest of, any such Sum of Money which shall become payable as aforesaid; or to accelerate the Time of the Delivery of any Goods, Chattles, Wares, Merchandize or other Things whatsoever . . .It goes on in that vein for quite a while, and in particular, it says that "all and every such Rent and Rents. . . shall remain and continue to be due and payable; at and upon the same respective natural Days and Times, as the same should and ought to have been payable or made, or would have happened, in case this Act had not been made. . . ". It also specifies that interest payments are to be reckoned according to the natural number of days elapsed, not according to the calendar dates. There is also a special clause asserting that no person shall be deemed to have reached the age of twenty-one years until they are actually twenty-one years old, calendrical trickery notwithstanding.

I first brought this up in connection with Benjamin Franklin's 300th birthday, saying that although Franklin had been born on 6 January, 1706, his birthday had been moved up 11 days by the Act. But things seem less clear to me now that I have reread the act. I thought there was a clause that specifically moved birthdays forward, but there isn't. There is the clause that says that Franklin cannot be said to be 300 years old until 17 January, and it also says that dates of delivery of merchandise should remain on the same real days. If you had contracted for flowers and cake to be delivered to a birthday party to be held on 6 January 2006, the date of delivery is advanced so that the florist and the baker have the same real amount of time to make delivery, and are now required to deliver on 17 January 2006.

But there is the additional confusion I had forgotten, which is that Franklin was born on 6 January 1706, and there was no 6 January 1751. What would have been 6 January 1751 was renominated to be 6 January 1752 instead, and then the old 6 January 1752 was renominated as 17 January 1753.

To make the problem more explicit, consider John Smith, born 1 January 1750. The previous day was 31 December 1750, not 1749, because 1749 ended nine months earlier, on March 24. Similarly, 1751 will not begin until 25 March, when John is 84 days old. 1751 is an oddity, and ends on December 31, when John is 364 days old. The following day is 1 January 1752, and John is now one year old. Did you catch that? John was born on 1 January 1750, but he is one year old on 1 January 1752. Similarly, he is two years old on 1 January 1753.

The same thing happens with Benjamin Franklin. Franklin was born on 6 January 1706, so he will be 300 years old (that is, 365 × 300 + 73 = 109573 days old) on 17 January 2007.

So I conclude that the cake and flowers for Franklin's 300th birthday celebration are being delivered a year early!

[ Addendum: Why it was 3–13 September. ] [ Addendum: 2006 is the correct year for Franklin's 300th birthday. [1] [2] ]

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link