Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2025: | JFMAM |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 99 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 15 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Sun, 20 Mar 2016

Technical jargon failure modes

Technical jargon is its own thing, intended for easy communication between trained practitioners of some art, but not necessarily between anyone else.

Jargon can be somewhat transparent, like the chemical jargon term “alcohol”. “Alcohol” refers to a large class of related chemical compounds, of which the simplest examples are methyl alcohol (traditionally called “wood alcohol”) and ethyl alcohol (the kind that you get in your martini). The extension of “alcohol” to the larger class is suggestive and helpful. Someone who doesn't understand the chemical jargon usage of “alcohol” can pick it up by analogy, and even if they don't they will probably have something like the right idea. A similar example is “aldehyde”. An outsider who hears this for the first time might reasonably ask “does that have something to do with formaldehyde?” and the reasonable answer is “yes indeed, formaldehyde is the simplest example of an aldehyde compound.” Again the common term is adapted to refer to the members of a larger but related class.

An opposite sort of adaptation is found in the term “bug”. The common term is extremely broad, encompassing all sorts of terrestrial arthropods, including mosquitoes, ladybugs, flies, dragonflies, spiders, and even isopods (“pillbugs”) and centipedes and so forth. It should be clear that this category is too large and heterogeneous to be scientifically useful, and the technical use of “bug” is much more restricted. But it does include many creatures commonly referred to as bugs, such as bed bugs, waterbugs, various plant bugs, and many other flat-bodied crawling insects.

Mathematics jargon often wanders in different directions. Some mathematical terms are completely opaque. Nobody hearing the term “cobordism” or “simplicial complex” or “locally compact manifold” for the first time will think for an instant that they have any idea what it means, and this is perfect, because they will be perfectly correct. Other mathematical terms are paradoxically so transparent seeming that they reveal their opacity by being obviously too good to be true. If you hear a mathematician mention a “field” it will take no more than a moment to realize that it can have nothing to do with fields of grain or track-and-field sports. (A field is a collection of things that are number-like, in the sense of having addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division that behave pretty much the way one would expect those operations to behave.) And some mathematical jargon is fairly transparent. The non-mathematician's idea of “line”, “ball”, and “cube” is not in any way inconsistent with what the mathematician has in mind, although the full technical meaning of those terms is pregnant with ramifications and connotations that are invisible to non-mathematicians.

But mathematical jargon sometimes goes to some bad places. The term “group” is so generic that it could mean anything, and outsiders often imagine that it means something like what mathematicians call a “set”. (It actually means a family of objects that behave like the family of symmetries of some other object.)

This last is not too terrible, as jargon failures go. There is a worse kind of jargon failure I would like to contrast with “bug”. There the problem, if there is a problem, is that entomologists use the common term “bug” much more restrictively than one expects. An entomologist will well-actually you to explain that a millipede is not actually a bug, but we are used to technicians using technical terms in more restrictive ways than we expect. At least you can feel fairly confident that if you ask for examples of bugs (“true bugs”, in the jargon) that they will all be what you will consider bugs, and the entomologist will not proceed to rattle off a list that includes bats, lobsters, potatoes, or the Trans-Siberian Railroad. This is an acceptable state of affairs.

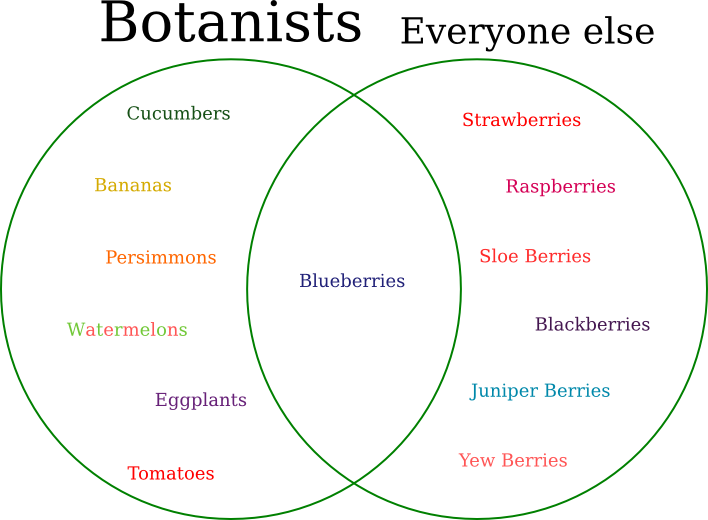

Unacceptable, however, is the botanical use of the term “berry”:

It is one thing to adopt a jargon term that is completely orthogonal to common usage, as with “fruit”, where the technical term simply has no relation at all to the common meaning. That is bad enough. But to adopt the term “berry” for a class of fruits that excludes nearly everything that is commonly called a ”berry” is an offense against common sense.

This has been on my mind a long time, but I am writing about it now because I think I have found, at last, an even more offensive example.

Stonehenge is so-called because it is a place of hanging stones: “henge” is cognate with “hang”.

In 1932 archaeologists adapted the name “Stonehenge” to create the word “henge” as a generic term for a family of ancient monuments that are similar to Stonehenge.

Therefore, if there were only one thing in the whole world that ought to be an example of a henge, it should be Stonehenge.

However, Stonehenge is not, itself, a henge.

Stonehenge is not a henge.

STONEHENGE IS NOT A HENGE.

Stonehenge is not a henge. … Technically, [henges] are earthwork enclosures in which a ditch was dug to make a bank, which was thrown up on the outside edge of the ditch.

— Michael Pitts, Hengeworld, pp. 26–28.

“Henge” may just be the most ineptly coined item of technical jargon in history.

[ Addendum 20161103: Zimbabwe's Great Dyke is not actually a dyke. ]

[ Addendum 20190502: I found a mathematical example that is approximately as bad as the worst examples on this page. ]

[Other articles in category /lang] permanent link

Sat, 19 Mar 2016

Sympathetic magic for four-year-olds

When Katara was about four, she was very distressed by the idea that green bugs were going to invade our house, I think though the mail slot in the front door. The obvious thing to do here was to tell her that there are no green bugs coming through the mail slot and she should shut up and go to sleep, but it seems clear to me that this was never going to work.

(It surprises me how few adults understand that this won't work. When Marcie admits at a cocktail party that she is afraid that people are staring at her in disgust, wondering why her pores are so big, many adults—but by no means all—know that it will not help her to reply “nobody is looking at your pores, you lunatic,” however true that may be. But even most of these enlightened adults will not hesitate to say the equivalent thing to a four-year-old afraid of mysterious green bugs. Adults and children are not so different in their irrational fears; they are just afraid of different kinds of monsters.)

Anyway, I tried to think what to say instead, and I had a happy idea. I told Katara that we would cast a magic spell to keep out the bugs. Red, I observed, was the opposite of green, and the green bugs would be powerfully repelled if we placed a bright red object just inside the front door where they would be sure to see it. Unwilling to pass the red object, they would turn back and leave us alone. Katara found this theory convincing, and so we laid sheets of red construction paper in the entryway under the mail slot.

Every night before bed for several weeks we laid out the red paper, and took it up again in the morning. This was not very troublesome, and certainly it less troublesome than arguing about green bugs every night with a tired four-year-old. For the first few nights, she was still a little worried about the bugs, but I confidently reminded her that the red paper would prevent them from coming in, and she was satisfied. The first few nights we may also have put red paper inside the door of her bedroom, just to be sure. Some nights she would forget and I would remind her that we had to put out the red paper before bedtime; then she would know that I took the threat seriously. Other nights I would forget and I would thank her for reminding me. After a few months of this we both started to forget, and the phase passed. I suppose the green bugs gave up eventually and moved on to a less well-defended house.

Several years later, Katara's younger sister Toph had a similar concern: she was afraid the house would be attacked by zombies. This time I already knew what to do. We discussed zombies, and how zombies are created by voodoo magic; therefore they are susceptible to voodoo, and I told Toph we would use voodoo to repel the zombies. I had her draw a picture of the zombies attacking the house, as detailed and elaborate as possible. Then we took black paper and cut it into black bars, and pasted the bars over Toph's drawing, so that the zombies were in a cage. The cage on the picture would immobilize the real zombies, I explained, just as one can stick pins into a voodoo doll of one's enemy to harm the real enemy. We hung the picture in the entryway, and Toph proudly remarked on how we had stopped the zombies whenever we went in or out.

Rationality has its limits. It avails nothing against green bugs or murderous zombies. Magical enemies must be fought with magic.

[Other articles in category /kids] permanent link