Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JAS | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 99 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Wed, 14 Aug 2024

Benjamin Franklin wrote and published Poor Richard's Almanack annually from 1732 to 1758. Paper was expensive and printing difficult and time-consuming. The type would be inked, the sheet of paper laid on the press, the apprentices would press the sheet, by turning a big screw. Then the sheet was removed and hung up to dry. Then you can do another printing of the same page. Do this ten thousand times and you have ten thousand prints of a sheet. Do it ten thousand more to print a second sheet. Then print the second side of the first sheet ten thousand times and print the second side of the second sheet ten thousand times. Fold 20,000 sheets into eighths, cut and bind them into 10,000 thirty-two page pamphlets and you have your Almanacks.

As a youth, Franklin was apprenticed to his brother James, also a printer, in Boston. Franklin liked the work, but James drank and beat him, so he ran away to Philadelphia. When James died, Benjamin sent his widowed sister-in-law Ann five hundred copies of the Almanack to sell. When I first heard that I thought it was a mean present but I was being a twenty-first-century fool. The pressing of five hundred almanacks is no small feat of toil. Ann would have been able to sell those Almanacks in her print shop for fivepence each, or ₤10 8s. 4d. That was a lot of money in 1735.

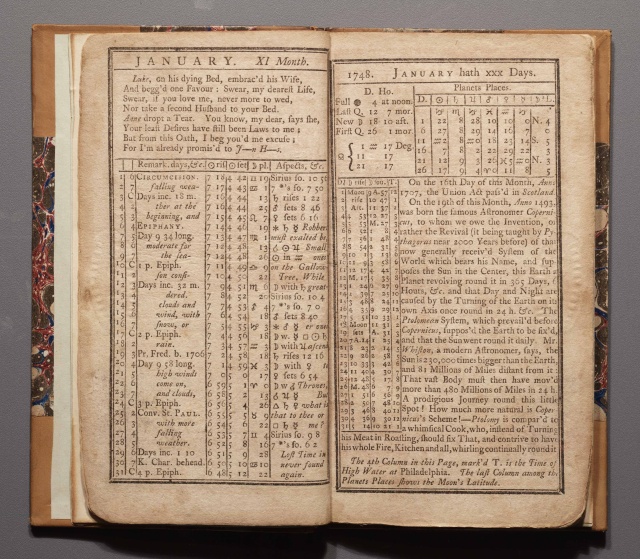

In 1748 Franklin increased the size and the price. Here's a typical page from the 1748 Almanack:

Wow, there's a lot of stuff going on there. Here's a smaller excerpt, this time from November 1753:

The leftmost column is the day of the month, and then the next column is the day of the week, with 2–7 being Monday through Saturday. Sunday is denoted with a letter “G”. I thought this was G for God, but I see that in 1748 Franklin used “C” and in 1752 he used “A”, so I don't know.

The third column combines a weather forecast and a calendar. The weather forecast is in italic type, over toward the right: “Clouds and threatens cold rains and snow” in the early part of the month. Sounds like November in Philadelphia. The roman type gives important days. For example, November 1 is All Saints Day and November 5 is the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot. November 10 is given as the birthday of King George II, then still the King of Great Britain.

The Sundays are marked with some description in the Christian liturgical calendar. For example, “20 past Trin.” means it's the start of the 20th week past Trinity Sunday.

This column also has notations like “Days dec. 4 32” and “Days dec. 5 h.” that I haven't been able to figure out. Something about the decreasing length of the day in November maybe? [ Addendum: Yes. See below. ] The notation on November 6 says “Day 10 10 long” which is consistent with the sunrise and sunset times Franklin gives for that day. The fourth and fifth columns, labeled “☉ ris” and “☉ set” are the times of sunrise and sunset, 6:55 (AM) and 5:05 (PM) respectively for November 6, ten hours and ten minutes apart as Franklin says.

“☽ pl.” is the position of the moon in the sky. (I guess “pl.” is short for “place”.) The sky is divided into twelve “houses” of 30 degrees each, and when it says that the “☽ pl.” on November 6 is “♓ 25” I think it means the moon is !!\frac{25}{30}!! of the way along in the house of Pisces on its way to the house of Aries ♈. If you look at the January 1748 page above you can see the moon making its way through the whole sky in 29 days, as it does.

The last column, “Aspects, &c.” contains more astronomy. “♂ rise 6 13” means that Mars will rise at 6:13 that day. (But in the morning or the evening?) ⚹♃♀ on the 12th says that Jupiter is in sextile aspect to Venus, which means that they are in the sky 60 degrees apart. Similarly □☉♃ means that the Sun and Jupiter are in Square aspect, 90 degrees apart in the sky.

Also mixed into that last column, taking up the otherwise empty space, are the famous wise sayings of Poor Richard. Here we see:

Serving God is Doing Good to Man,

but Praying is thought an easier Service,

and therefore more generally chosen.

Back on the January page you can see one of the more famous ones, Lost Time is never found again.

Franklin published an Almanack in 1752, the year that the British Calendar Act of 1751 updated the calendar from Julian to Gregorian reckoning. To bring the calendar into line with Gregorian, eleven days were dropped from September that year. I wondered what Franklin's calendar looked like that month. Here it is with the eleven days clearly missing:

The leftmost day-of-the-month column skips right from September 2 to September 14, as the law required. On this copy someone has added the old dates in the margin. Notice that St. Michael's Day, which would have been on Friday September 18th in the old calendar, has been moved up to September 29th. In most years Poor Richard's Almanack featured an essay by Poor Richard, little poems, and other reference material. The 1752 Almanack omitted most of this so that Franklin could use the space to instead reprint the entire text of the Calendar Act.

This page also commemorates the Great Fire of London, which began September 2, 1666.

Wikipedia tells me that Franklin may have gotten the King's birthday wrong. Franklin says November 10, but Wikipedia says November 9, and:

Over the course of George's life, two calendars were used: the Old Style Julian calendar and the New Style Gregorian calendar. Before 1700, the two calendars were 10 days apart. Hanover switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar on 19 February (O.S.) / 1 March (N.S.) 1700. Great Britain switched on 3/14 September 1752. George was born on 30 October Old Style, which was 9 November New Style, but because the calendar shifted forward a further day in 1700, the date is occasionally miscalculated as 10 November.

Ugh, calendars.

I got these scans from a web site called The Rare Book Room, but I found their user interface very troublesome, so I have scraped all the images they had. You may find them at https://pic.blog.plover.com/calendar/poor-richards-almanack/archive/. I'm pretty sure the copyright has expired, so share and enjoy.

Addenda

Several people have pointed out that the mysterious letters G, C, A on Sundays are the so-called dominical letters, used in remembering the correspondence between days of the month and days of the week, and important in the determination of the dates of Easter and other moveable feasts.

Why Franklin included them in the Almanack is not clear to me, as one of the main purposes of the almanac itself is so that you do not have to remember or calculate those things, you can just look them up in the almanac.

Mikkel Paulson explained the 'days dec.' and 'days inc.' notations: they describe the length of the day, but reported relative to the length of the most recent solstice. For example, the November 1753 excerpt for November 2 says "Days dec. 4 32". Going by the times of sunrise and sunset on that day, the day was 10 hours 18 minutes long. Adding the 4 hours 32 minutes from the notation we have 14 hours 50 minutes, which is indeed the length of the day on the summer solstice in Philadelphia, or close to it.

Similarly the notation on November 14 says "Days dec. 5 h" for a day that is 9 hours 50 minutes between sunrise and sunset, five hours shorter than on the summer solstice, and the January 3 entry says "Days inc. 18 m." for a 9h 28m day which is 18 minutes longer than the 9h 10m day one would have on the winter solstice.

[Other articles in category /calendar] permanent link