Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | J |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Mon, 28 Feb 2022

Quicker and easier ways to get more light

Hacker News today is discussing this article by Lincoln Quirk about ways to get more light in your home office.

Why?

You might do this because you have trouble seeing.

Or because you find you are more productive when the room is brighter.

Or perhaps you have seasonal affective disorder, for which more light is a recognized treatment. For SAD you can buy these cute little light therapy boxes that are supposed to help, but they don't, because they are not bright enough to make a difference. Waste of money.

Quirk's summary

Quirk says:

I want an all-in-one “light panel” that produces at least 20000 lumens and can be mounted to a wall or ceiling, with no noticeable flicker, good CRI, and adjustable (perhaps automatically adjusting) color temperature throughout the day.

and describes some possible approaches.

One is to buy 25 ordinary LED bulbs, and make some sort of contraption to mount them on the wall or ceiling. This is cheap, but you have to figure out how to mount the bulbs and then you have to do it. And you have to manage 25 bulbs, which might annoy you.

Quirk points out that 815-lumen LED bulbs can be had for $1.93, for a cost of $2.75 / kilolumen (klm).

Another suggestion of Quirk's is to use LED strips, but I think you'd have to figure out how to control them, and they are expensive: Quirk says $16 / klm.

Here's what I did that was easy and relatively inexpensive

This thing is a “corn bulb”, so-called because it is a long cylinder with many LEDs arranged on in like kernels on a corn cob. A single bulb fits into a standard light socket but delivers up to twelve times as much light as a standard bulb.

You can buy them from the DragonLight company.

| power | Cost | Luminance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (W) | (lm) | (bulbs) | |

| 25 | $22 | 3000 | 1.9 |

| 35 | $26 | 4200 | 2.6 |

| 50 | $33 | 6000 | 3.8 |

| 54 | $35 | 6200 | 3.9 |

| 80 | $60 | 9600 | 6 |

The fourth column is the corn bulb's luminance compared with a standard 100W incandescent bulb, which I think emits around 1600 lm.

Cost varies from $7.33 / klm at the top of the table to $4.93 / klm at the bottom.

I got an 80-watt corn bulb ($60) for my office. It is really bright, startlingly bright, too bright to look at directly. It was about a month before I got used to it and stopped saying “woah” every time I flipped the switch. I liked it so much I bought a 120-watt bulb for the other receptacle. I'd like to post a photo, but all you would be able to see is a splotch.

The two bulbs cost around $140 total and jointly deliver 24,000 lumens, which is as much light as 15 or 16 bright incandescent bulbs, for $5.83 / klm. It's twice as expensive as the cheap solution but has the great benefit that I didn't have to think about it, it was as simple as putting new bulbs into the two sockets I already had. Also, as I said, I started with one $60 bulb to see whether I liked it. If you are interested in what it is like to have a much better-lit room, this is a low-risk and low-effort way to find out.

Corn bulbs are available in different color temperatures. In my view the biggest drawback is that each bulb carries a cooling fan built into its base. The fan runs at 40–50 dB, and many people would find it disturbing. [Addendum 20220403: Fanless bulbs are now available. See below.] Lincoln Quirk says he didn't like the light quality; I like it just fine. The color is not adjustable, but if you have two separately-controllable sockets you could put a bulb of one color in each socket and switch between them.

I found out about the corn bulbs from YOU NEED MORE LUMENS by David Chapman, and Your room can be as bright as the outdoors by Ben Kuhn. Thanks very much to Benjamin Esham for figuring this out for me; I had forgotten where I got the idea.

[ Addendum 20220403: Gábor Lehel points out that DragonLight now sells fanless bulbs in all wattages. Apparently because the bulb housing is all-aluminum, the bulb can dissipate enough heat even without the fan. Thanks! ]

[Other articles in category /tech] permanent link

Sat, 26 Feb 2022

I vent my rage at dumbass Math SE comments

[ Content warning: ranting ]

An article I've had in progress for a while is an essay about the dogmatic slogan that “infinity is not a number”. As research for that article I got Math Stack Exchange to disgorge all the comments that used that phrase. There were several dozen.

Most of them were just inane, or ill-considered; some contained genuine technical errors. But this one was so annoying that I have paused to complain about it individually:

One thing many laypeople do not understand or realize is that infinity is not a number, it's not equal to any number, and that two infinities can be different (or the same) in size from one another."

That is not “one thing”. It is three things.

A person who is unclear on the distinction between !!1!! and !!3!! should withhold their opinions about the nature of infinity.

[ Addendum 20220301: I did not clearly communicate which side of the “infinity is not a number” issue I am on. Here's my preliminary statement on the matter: The facile and prevalent claim that “infinity is not a number”, to the extent that it isn't inane, is false. I hope this is sufficiently clear. ]

[Other articles in category /math/se] permanent link

Thu, 24 Feb 2022

More about the axioms of infinity and the empty set

[ Content warning: inconclusive nattering ]

Yesterday I discussed how one can remove the symbol !!\varnothing!! from the statement of the axiom of infinity (“!!A_\infty!!”). Normally, !!A_\infty!! looks like this:

$$\exists S (\color{darkblue}{\varnothing \in S}\land (\forall x\in S) x\cup\{x\}\in S).$$

But the “!!\varnothing!!” is just an abbreviation for “some set !!Z!! with the property !!\forall y. y\notin Z!!”, so one should understand the statement above as shorthand for:

$$\exists S (\color{darkblue}{(\exists Z.(\forall y. y\notin Z)\land (Z \in S))} \\ \land (\forall x\in S) x\cup\{x\}\in S).\tag{$\heartsuit$}$$

(The !!\cup!! and !!\{x\}!! signs should be expanded analogously, as abbreviations for longer formulas, but we will ignore them today.)

Thinking on it a little more, I realized that you could conceivably get into big trouble by doing this, for a reason very much like the one that concerned me initially. Suppose that, in !!(\heartsuit)!!, in place of $$\exists Z.(\color{darkgreen}{\forall y. y\notin Z})\land (Z \in S),$$ we had $$\exists Z.(\color{darkred}{\forall y. y\in Z\iff y\notin y})\land (Z \in S).$$

Now instead of !!Z!! having the empty-set property, it is required to have the Russell set property, and we demand that the infinite set !!S!! include an element with that property. But there is provably no such !!Z!!, which makes the axioms inconsistent. My request that !!\varnothing!! be proved to exist before it be used in the construction of !!S!! was not entirely silly.

My original objection partook of a few things:

- You ought not to use the symbol “!!\varnothing!!” without defining it

I believe that expanding abbreviations as we did above addresses this issue adequately.

- But to be meaningful, any such definition requires an existence proof and perhaps even a uniqueness proof

“Meaningful” is the wrong word here. I'm willing to agree that the defined symbol necessarily has a sense. But without an existence proof the symbol may not refer to anything. This is still a live issue, because if the symbol doesn't denote anything, your axiom has a big problem and ruins the whole theory. The axiom has a sense, but if it asserts the existence of some derived object, as this one does, the theory is inconsistent, and if it asserts the universality of some derived property, the theory is vacuous.

I think embedding the existence claim inside another axiom, as is done in !!(\heartsuit)!!, makes it easier to overlook the existence issue. Why use complicated axioms when you could use simpler ones? But technically this is not a big deal: if !!Z!! doesn't exist, then neither does !!S!!, and the axioms are inconsistent, regardless of whether we chose to embed the definition of !!Z!! in !!A_\infty!! or leave it separate.

One reason to prefer simpler axioms is that we hope it will be easier to detect that something is wrong with them. But set theorists do spend a lot of time thinking about the consistency of their theories, and understand the consistency issues much better than I do. If they think it's not a problem to embed the axiom of the empty set into !!A_\infty!!, who am I to disagree?

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link

Wed, 23 Feb 2022

My mistake about errors in the presentation of axiomatic set theory

[ Content warning: highly technical mathematics ]

A couple of weeks ago I claimed:

Many presentations of axiomatic set theory contain an error

I realized recently that there's a small but significant error in many presentations of the Zermelo-Frankel set theory: Many authors omit the axiom of the empty set, claiming that it is omittable. But it is not.

Well, it sort of is and isn't at the same time. But the omission that bothered me is not really an error. The experts were right and I was mistaken.

(Maybe I should repeat my disclaimer that I never thought there was a substantive error, just an error of presentation. Only a crackpot would reject the substance of ZF set theory, and I am not prepared to do that this week.)

My argument was something like this:

You want to prevent the axioms from being vacuous, so you need to be able to prove that at least one set exists.

One way to do this is with an explicit “axiom of the empty set”: $$\exists Z. \forall y. y\notin Z$$

But many presentations omit this, remarking that the axiom of infinity (“!!A_\infty!!”) also asserts the existence of a set, and the empty set can be obtained from that one via specification.

The axiom of infinity is usually stated in this form: $$\exists S (\varnothing \in S\land (\forall x\in S) x\cup\{x\}\in S).$$ But, until you prove that the empty set actually exists, it is not meaningful to include the symbol !!\varnothing!! in your axiom, since it does not actually refer to anything, and the formula above is formally meaningless.

I ended by saying:

You really do need an explicit axiom [of the empty set]. As far as I can tell, you cannot get away without it.

Several people tried to explain my error, pointing out that !!\varnothing!! is not part of the language of set theory, so the actual formal statement of !!A_\infty!! doesn't include the !!\varnothing!! symbol anyway. But I didn't understand the point until I read Eike Schulte's explanation. M. Schulte delved into the syntactic details of what we really mean by abbreviations like !!\varnothing!!, and why they are meaningful even before we prove that the abbreviation refers to something. Instead of explicitly mentioning !!\varnothing!!, which had bothered me, M. Schulte suggested this version of !!A_\infty!!:

$$\exists S (\color{darkblue}{(\exists Z.(\forall y. y\notin Z)\land (Z \in S))} \\ \land (\forall x\in S) x\cup\{x\}\in S).$$

We don't have to say that !!S!! (the infinite set) includes !!\varnothing!!, which is subject to my quibble about !!\varnothing!! not being meaningful. Instead we can just say that !!S!! includes some element !!Z!! that has the property !!\forall y.y\notin Z!!; that is, it includes an element !!Z!! that happens to be empty.

A couple of people had suggested something like this before M. Schulte did, but I either didn't understand or I felt this didn't contradict my original point. I thought:

I claimed that you can't get rid of the empty set axiom. And it hasn't been gotten rid of; it is still there, entire, just embedded in the statement of !!A_\infty!!.

In a conversation elsewhere, I said:

You could embed the axiom of pairing inside the axiom of infinity using the same trick, but I doubt anyone would be happy with your claim that the axiom of pairing was thereby unnecessary.

I found Schulte's explanation convincing though. The !!A_\infty!! that Schulte suggested is not a mere conjunction of axioms. The usual form of !!A_\infty!! states that the infinite set !!S!! must include !!\varnothing!!, whatever that means. The rewritten form has the same content, but more explicit: !!S!! must include some element !!Z!! that has the emptiness property (!!\forall y. y\notin Z!!) that we want !!\varnothing!! to have.

I am satisfied. I hereby recant the mistaken conclusion of that article.

Thanks to everyone who helped me out with this: Ben Zinberg, Asaf Karagila, Nick Drozd, and especially to Eike Schulte. There are now only 14,823,901,417,522 things remaining that I don't know. Onward to zero!

[ Addendum 20220224: A bit more about this. ]

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link

Tue, 22 Feb 2022

“Shall” and “will” strike back from beyond the grave

In former times and other dialects of English, there was a distinction between ‘shall’ and ‘will’. To explain the distinction correctly would require research, and I have a busy day today. Instead I will approximate it by saying that up to the middle of the 19th century, ‘shall’ referred to events that would happen in due course, whereas ‘will' was for events brought about intentionally, by force of will. An English child of the 1830's, stamping its foot and shouting “I will have another cookie”, was expressing its firm intention to get the cookie against all opposition. The same child shouting “I shall have another cookie” was making a prediction about the future that might or might not have turned out to be correct.

In American English at least, this distinction is dead. In The American Language, H.L. Mencken wrote:

Today the distinction between will and shall has become so muddled in all save the most painstaking and artificial varieties of American that it may almost be said to have ceased to exist.

That was no later than 1937, and he had been observing the trend as early as the first edition (1919):

… the distinction between will and shall, preserved in correct English but already breaking down in the most correct American, has been lost entirely in the American common speech.

But yesterday, to my amazement, I found myself grappling with it! I had written:

The problem to solve here … [is] “how can OP deal with the inescapable fact that they can't and won't pass the exam”.

To me, the “won't” connoted a willful refusal on the part of OP, in the sense of “I won't do it!”, and not what I wanted to express, which was an inevitable outcome. I'm not sure whether anyone else would have read it the same way, but I was happier after I rewrote it:

The problem to solve here … [is] “how can OP deal with the inescapable fact that they cannot and will not pass the exam”.

I could also gotten the meaning I wanted by replacing “can't and won't” with “can't and shan't” — except that “shan't’ is dead, I never use it, and, had I thought of it, I would have made a rude and contemptuous nose noise.

Mencken says “the future in English is most commonly expressed by neither shall nor will, but by the must commoner contraction 'll’. In this case that wasn't true! I wonder if he missed the connotation of “won't” that I felt, or if the connotation arose after he wrote his book, or if it's just something idiosyncratic to me.

[Other articles in category /lang] permanent link

Mon, 21 Feb 2022

What to do if you're about to fail real analysis for the second time?

A few months ago a Reddit user came to r/math

with this tale of woe:

I failed real analysis horrifically the first time … and my resit takes place in a few days. I still feel completely and utterly unprepared. I can't do the homework questions and I can't do the practice papers. I'm really quite worried that I'll fail and have to resit the whole year (can't afford) or get kicked out of uni (fuck that).

Does anyone have tips or advice, or just any general words of comfort to help me through this mess? Cheers.

The first thing that came to mind for me was “wow, you're fucked”. There was a time in my life when I might have posted that reply but I'm a little more mature now and I know better.

I read some of the replies. The top answer was a link to a pirated copy of Aksoy and Khamsi's A Problem Book in Real Analysis. A little too late for that, I think. Hapless OP must re-sit the exam in a few days and can't do the homework questions or practice papers; the answer isn't simply “more practice”, because there isn't time.

The second-highest-voted reply was similar: “Pick up Stephen Abbott's Understanding Analysis”. Same. It's much too late for that.

The third reply was fatuous: “understand the proofs done in the

textbook/lecture completely, since a lot of the techniques used to

prove those statements you will probably need to use while doing

problems”. <sarcasm>Yes, great advice, to pass the exam just understand the

material completely, so simple, why doesn't everyone just do that?</sarcasm>

Here's one I especially despised:

Don't worry. Real analysis is a lot of work and you never have the time to understand everything there.

“Don't worry”! Don't worry about having to repeat the year? Don't worry about getting kicked out of university? I honestly think “wow, you're fucked” would be less damaging. In the book of notoriously ineffective problem-solving strategies, chapter 1 is titled “Pretend there is No Problem”.

This was amusing but unhelpful:

We are all going to die. Compared to death, real analysis is nothing to fear.

(However, another user disagreed: “Compared to real analysis, death is nothing to fear”.)

Some comments offered hints: focus on topology, try proof by contradiction. Too little, and much too late.

Most of the practical suggestions, in my opinion, were answering the wrong question. They all started from the premise that it would be possible for Hapless OP to pass the exam. I see no evidence that this was the case. If Hapless OP had showed up on Reddit having failed the midterm, or even a few weeks ahead of the final, that would be a very different situation. There would still have been time to turn things around. OP could get tutoring. They could go to office hours regularly. They could organize a study group. They could work hard with one of those books that the other replies mentioned. But with “a few days” left? Not a chance.

The problem to solve here isn't “how can OP pass the exam”. It's “how can OP deal with the inescapable fact that they cannot and will not pass the exam”.

Way downthread there was some advice (from user tipf) that was gloomy but which, unlike the rest of the comments, engaged the real issue, that Hapless OP wasn't going to pass the exam the following week:

I would seriously rethink getting a pure math major. It's not a very marketable major outside academia, and sinking a bunch of money into it (e.g. re-taking a whole year) is just not a good idea under almost any circumstance.

Pessimistic, yes, but unlike the other suggestions, it actually engages with Hapless OP's position as they described it (“have to resit the whole year (can't afford)”).

When we reframe the question as “how can OP deal the fact that they won't pass the exam”, some new paths become available for exploration. I suggested:

[OP] should go consult with the math department people immediately, today, explain that they are not prepared and ask what can be done. Perhaps there is no room for negotiation, but in that case OP would be no worse off than they are now. But there may be an administrative solution.

For example, just hypothetically, what if the math department administrative assistant said:

You can get special permission to re-sit the exam in three months time, if you can convince the Dean that you had special extenuating hardships.

This is not completely implausible, and if true might put Hapless OP in a much better position!

Now you might say “Dominus, you just made that up as an example, there is no reason to think it is actually true.” And you would be quite correct. But we could make up fifty of these, and the chances would pretty good that one of them was actually true. The key is to find out which one.

And OP can't find out what is available unless they go talk to someone in the math department. Certainly not by moping in their room reading Reddit. Every minute spent moping is time that could be better spent tracking down the Dean, or writing the letter, or filing the forms, or whatever might be required to improve the situation.

Along the same lines, I suggested:

perhaps the department already has a plan for what to do with people who can't pass real analysis. Maybe they will say something constructive like “many people in your situation change to a Statistics major” or something like that.

I don't know if Hapless OP would have been happy with a Statistics major; they didn't say. But again, the point is, there may be options that are more attractive than “get kicked out of uni”, and OP should go find out what they are.

The higher-level advice here, which I think is generally good, is that while asking on Reddit is quick and easy, it's not likely to produce anything of value. It's like looking for your lost wallet under the lamppost because the light is good. But it doesn't work; you need to go ask the question to the people who actually know what the solutions might be and who are in a position to actually do something about the problem.

[ Addendum 20220222: Still higher-level advice is: if you're losing the game, try instead playing the different game that is one level up. ]

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link

Fri, 11 Feb 2022

Geometric proof that the mediant lies between its arguments

The mediant of two fractions !!\frac ab!! and !!\frac cd!! is simply !!\frac{a+c}{b+d}!!. It appears often in connection with the theory of continued fractions, and a couple of months ago I put it to use in this post about Newton's method. There the crucial property was that if $$\frac ab < \frac cd$$ then $$\frac ab < \frac{a+c}{b+d} < \frac cd.$$

This can be proved with straightforward algebra:

$$\begin{align} \frac ab & < \frac cd \\ ad & < bc \\ ab + ad & < ab + bc \\ a(b+d) & < (a+c) b \\ \frac ab & < \frac{a+c}{b+d} \end{align}$$

and similarly for the !!\frac cd!! side.

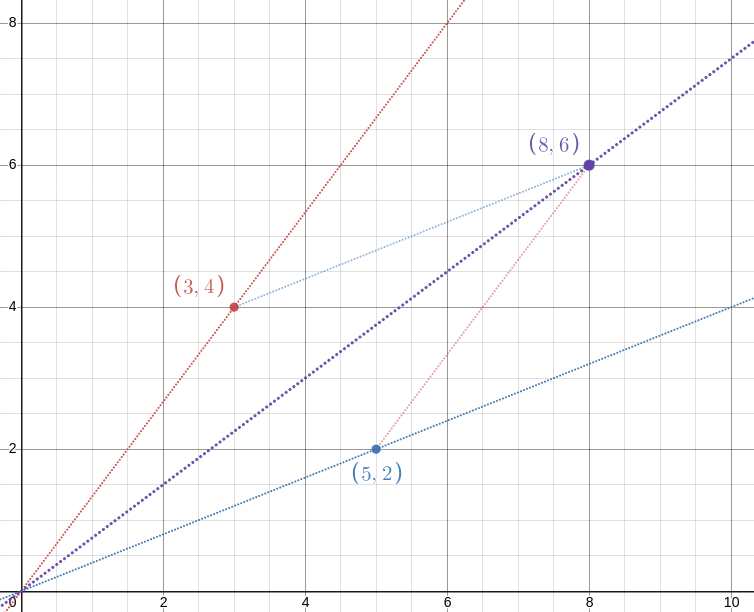

But Reddit user asenseofbeauty recently suggested a lovely visual proof that makes the result intuitively clear:

!!\def\pt#1#2{\langle{#1},{#2}\rangle}!! The idea is simply this: !!\frac ab!! is the slope of the line from the origin !!O!! through the point !!P=\pt ba!! (blue) and !!\frac cd!! is the slope of the line through !!Q=\pt dc!! (red). The point !!\pt{b+d}{a+c}!! is the fourth vertex of the parallelogram with vertices at !!O, P, Q!!, and !!\frac{a+c}{b+d}!! is the slope of the parallelogram's diagonal. Since the diagonal lies between the two sides, the slope must also lie in the middle somewhere.

The embedded display above should be interactive. You can drag around the red and blue points and watch the diagonal with slope !!\frac{a+b}{c+d}!! slide around to match.

In case the demo doesn't work, here's a screenshot showing that !!\frac 25 < \frac{2+4}{5+3} < \frac 43!!:

[ Addendum 20220215: The source was this Reddit comment from asenseofbeauty. ]

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link

Wed, 09 Feb 2022

If I haven't replied to your email about Haskell…

Perhaps someone out there wants to take a chance on a senior programmer with thirty years of experience who wants to make a move into Haskell.

This worked better than I expected. Someone posted it to Hacker News, and it reached #1. I got 45 emails with suggestions about where to apply, and some suggestions through other channels also. Many thanks to everyone who contributed.

I'm answering the messages in the order I received them. Thoughtful replies take time. If I haven't answered yours yet, it's not that I am uninterested, or I am blowing you off. It's because I got 45 emails.

Thanks for your patience and understanding.

[Other articles in category /meta] permanent link

Mon, 07 Feb 2022

I would like a job writing Haskell

Perhaps someone out there wants to take a chance on a senior programmer with thirty years of experience who wants to make a move into Haskell.

I'm between jobs right now, having resigned my old one without having a new one lined up. It's been a pleasant vacation but it can't go on forever. At some point I'll need another job.

I would really like it to be Haskell programming but I don't know where to look. I hope maybe one of my Gentle Readers does.

I don't have any professional or substantial Haskell experience, but a Haskell shop might be happy to get me anyway. I think I'm well-prepared to rapidly get up to speed writing production Haskell programs:

Although I have never been paid to write Haskell, I'm not a newbie. I have been using Haskell on and off for twenty years. I have been immersed in the Haskell ecosystem since the 1998 language standard was fresh. I've read the important papers. I know how the language has evolved. I know how to read the error messages. Haskell has featured regularly on my blog since I started it.

I solidly understand the Hindley-Milner type elaboration algorithm and the typeclass stuff that Haskell puts on top of that. I have successfully written many thousands of lines of SML, which uses an earlier version of the same system. I'm 100% behind the strong-typing philosophy.

I have a mathematics background. I know the applicable category theory. I understand what it means when someone says that a monad is a monoid in the category of endofunctors. I won't be scared if someone talks about η-conversion, or confused if they talk about lifting a type.

I am quite comfortable with lazy data structures and with higher-order functional constructs such as parser combinators. In fact, I wrote a book about them.

I'm not sure I should admit this, but I'm the person who explained why monads are like burritos.

If you're interested, or if you know someone who might be,

here's my résumé.

please feel free to pass it around or to ask me questions at

mjd@pobox.com.

Thanks for your kind attention.

Big restriction: I live in Philadelphia and cannot relocate. I have no objection to occasional travel, and a long history of sucessful remote work.

[ Addendum 20220209: If you emailed me and haven't heard back, it's only because response was overwhelming and I haven't gotten to your message yet. Thank you! ]

[Other articles in category /meta] permanent link

Sun, 06 Feb 2022

A one-character omission caused my Python program to hang (not)

I just ran into a weird and annoying program behavior. I was

writing a Python program, and when I ran it, it seemed to hang.

Worried that it was stuck in some sort of resource-intensive loop I

interrupted it, and then I got what looked like an error message from

the interpreter. I tried this several more times, with the same

result; I tried putting exit(0) near the top of the program to

figure out where the slowdown was, but the behavior didn't change.

The real problem was that the first line which said:

#/usr/bin/env python3

when it should have been:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

Without that magic #! at the beginning, the file is processed not by

Python but by the shell, and the first thing the shell saw was

import re

which tells it to run the import command.

I didn't even know there was an import command. It runs an X client

that waits for the user to click on a window, and then writes a dump

of the window contents to a file. That's why my program seemed to

hang; it was waiting for the click.

I might have picked up on this sooner if I had actually looked at the error messages:

./license-plate-game.py: line 9: dictionary: command not found

./license-plate-game.py: line 10: syntax error near unexpected token `('

./license-plate-game.py: line 10: `words = read_dictionary(dictionary)'

In particular, dictionary: command not found is the shell giving

itself away. But I was so worried about the supposedly resource-bound

program crashing my session that I didn't look at the actual output,

and assumed it was Python-related syntax errors.

I don't remember making this mistake before but it seems like it would be an easy mistake to make. It might serve as a good example when explaining to nontechnical people how finicky and exacting programming can be. I think it wouldn't be hard to understand what happened.

This computer stuff is amazingly complicated. I don't know how anyone gets anything done.

[Other articles in category /Unix] permanent link

Sat, 05 Feb 2022

Factoring composite numbers into nearly equal factors

Pennsylvania license plate numbers have four digits and when I'm driving I habitually try to factor these. (This hasn't yet led to any serious injury or property damage…) In general factoring is a hardish problem but when !!n<10000!! the worst case is !!9991 = 97·103!! which is not out of reach. The toughest part is when you find a factor like !!661!! or !!667!! and have to decide if it is prime. For !!667!! you might notice right off that it is !!676-9 = (26+3)(26-3)!! but for !!661!! you have to wonder if maybe there is something like that and you just haven't thought of it yet. (There isn't.)

A related problem is the Nearly Equal Factors (NEF) problem: given

!!n!!, find !!a!! and !!b!!, as close as possible, with !!ab=n!!. If

!!n!! has one large prime factor, as it often does, this is quite

easy. For example suppose we are driving on the Interstate and are

behind a car with license plate GJA 6968. First we divide this by

!!8!!, so !!871!!, which is obviously not divisible by !!2, 3, 5, 7,!!

or !!11!!. So try !!13!!: !!871-780 = 91!! so !!871 = 13·67!!. If we

throw the !!67!! into the !!a!! pile and the other factors into the

!!b!! pile we get !!6968 = 67· 104!! and it's obvious we can't divide

up the factors more evenly: the !!67!! has to go somewhere and if we

put anything else with it, its pile is now at least !!2·67 = 134!!

which is already bigger than !!104!!. So !!67·104!! is the best we

can do.

When I first started thinking about this I thought maybe there could be a divide-and-conquer algorithm. For example, suppose !!n=4m!!. Then if we could find an optimal !!ab=m!!, we could conclude that the optimal factorization of !!n!! would simply be !!n = 2a· 2b!!. Except no, that is completely wrong; a counterexample is !!n=20!! where the optimal factorization is !!5·4!!, not !!(2·5)·(2·1)!!. So it's not that simple.

It's tempting to conclude that NEF is NP-hard, because it does look a lot like Partition. In Partition someone hands you a list of numbers and demands to know of they can be divided into two piles with equal sums. This is NP-hard, and so the optimization version of it, where you are asked to produce two piles as nearly equal as possible, is at least as hard. The NEF problem seems similar: if you know the prime factors !!n=p_1p_2…p_k!! then you can imagine that someone handed you the numbers !!\log p_1, … \log p_k!! and asked you to partition them into two nearly-equal piles. But this reduction is in the wrong direction; it only proves that Partition is at least as hard as NEF. Could there be a reduction in the other direction? I don't see anything obvious, but maybe there is something known about Partition or Knapsack that shows that even this restricted version is hard. [ Addendum: see below. ]

In practice, the first-fit-decreasing (FFD) algorithm usually performs well for this sort of problem. In FFD we go through the prime factors in decreasing order, and throw each one into the bin that is least full. This always works when there is one large prime factor. For example with !!6968!! we throw the !!67!! into the !!a!! bin, then the !!13!! and two of the !!2!!s into the !!b!! bin, at which point we have !!67·52!!, so the final !!2!! goes into the !!b!! bin also, and this is optimal. FFD does find the optimal solution much of the time, but not always. It works for !!20!! but fails for !!72 = 2^33^2!! because the first thing it does is to put the threes into separate bins. But the optimal solution !!72=9·8!! puts them in the same bin. Still it works for nearly all small numbers.

I would like to look into whether FFD it produces optimal results almost all of the time, and if so how almost? Wikipedia seems to say that the corresponding FFD algorithm for Partition, called LPT-first scheduling is guaranteed to produce a larger total which is no more than !!\frac76!! as big as the optimal, which would mean that for the NEF problem !!n=ab!! and !!a\ge b!! it will produce an !!a!! value no more than !!OPT^{7/6}!! where !!OPT!! is the minimum possible !!a!!.

Some small-number cases where FFD fails are:

$$ \begin{array}{rccc} n & \text{FFD} = ab & \text{Optimal} & \frac{\log(a)}{\log(OPT)} (≤ 1.167) \\ 72 & 12·6 & 9·8 & 1.131 \\ 180 & 18·10 & 15·12 & 1.067 \\ 240 & 20·12 & 16·15 & 1.080 \\ 288 & 24·12 & 18·16 & 1.100 \\ 336 & 28·12 & 21·16 & 1.094 \\ 540 & 30·18 & 27·20 & 1.032 \\ \end{array} $$

I wrote code to compute these and then I lost it.

I would also like to look at algorithms for NEF that don't begin by factoring !!n!!. We can guarantee to find optimal solutions with brute force, and in some cases this works very well. Consider !!240!! we begin by computing (in at most !!O(\log^2 n)!! time) the integer square root of !!240!!, which is !!15!!. Then since !!240!! is a multiple of !!15!! we have !!240=16·15!! and we win. In general of course it is not so easy, and it fails even in some cases where !!n!! is easy to factor. !!n=p^{2k+1}!! is especially unfortunate. Say !!n=243!! so the square root is !!15!!, which is not a factor of !!243!!. So we try !!14,!! then !!13,12,11,10!! and at last we find !!243=27·9!!.

[ Addendum 20220207: Dan Brumleve points out that it is NP-complete to decide whether, given numbers !!L, U, N!!, there is a number !!f!! in !! [L, U]!! that divides !!N!!. Using this, he shows that it is probably NP-complete to decide whether a given !!N!! is a product of two integers with !!\lvert a-b\rvert ≤ N^{1/4}!!. “Probably” here means that the reduction from Partition is polynomial time if Cramér's conjecture is correct. ]

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link

Today I learned that Julie Cypher, longtime partner of Melissa Etheridge, was actually born under the name Julie Cypher. Her dad's last name was Cypher, and it's apparently not even a very rare name.

It happens pretty often that I run into names and say to myself “wow, I'm glad that's not my name”. Or even “that's a cool name, but not as cool as ‘Dominus’.” But ‘Cypher’ is as cool as ‘Dominus’.

[ Addendum: I have mentioned before that Dominus is my birth name, not a recent invention. It came from Hungary, where it is in wider use than it is here. ]

[ Addendum 20220315: Today's “wow, I'm glad that's not my name” moment was in connection with Patience D. Roggensack. If you were writing a novel and gave a character that name, people would complain you were being precious. ]

[Other articles in category /misc/til] permanent link

Fri, 04 Feb 2022

An unexpected turn of phrase from Robertson Davies

Dave Turner has been tinkering with a game he calls Semantle and this reminded me of Robertson Davies' novel What's Bred in the Bone, which includes a minor character named Charlie Fremantle. This is how my brain works.

While I was looking up Charlie Fremantle I got sucked back into What's Bred in the Bone which is one of my favorite Davies novels. There is a long passage about Charlie and what he was like around 1933:

Charlie found Oxford painfully confining; he wanted to get out into the world and change it for the better, whether the world wanted it or not. He had advanced political ideas. He had read Marx — though not a great deal of him, for Charlie found thick, dense books a clog upon his soaring spirit. He had made a few Marxist speeches at the Union, and was admired by other untrammelled spirits like himself. His Marxism could be summed up as a conviction that whatever was, was wrong, and that the destruction of the existing order was the inevitable preamble to any beginning of the just society; the hope of the future lay with the workers, and all the workers needed was sympathetic leadership by people like himself, who had seen through the hypocrisy, stupidity, and bloody-mindedness of the upper class into which they themselves had been born.… Charlie was the upper class flinging itself into the struggle for justice on behalf of the oppressed; Charlie was Byron, determined to free the Greeks without having any clear notion of what or who the Greeks were; Charlie was a Grail knight of social justice.

A Grail knight of social justice! A social justice warrior! And one of a subtype we easily recognize among us even today. Davies wrote that sentence in 1985.

(But now that I look into it, I wonder what he meant to communicate by that phrase? In 1933, when that part of the book takes place, the phrase “social justice” was associated most closely with Father Charles Coughlin, founder of a political movement called the National Union for Social Justice, and publisher of the Social Justice periodical. Unlike Charlie, though, Coughlin was strongly anti-communist, which makes me wonder why Davies attached the phrase to him. Coincidence? I doubt that Davies was unaware of Coughlin in 1933, or had forgotten about him by 1985.)

[ A reader asks if Davies, as a Canadian, would have been aware of Father Coughlin. I think probably. Wikipedia says Coughlin's radio show reached millions of people, perhaps as many as 30 million a week. The show was based in Detroit, so many of these listeners must have been Canadian. At that time Davies was a university student in Kingston, Ontario. Coughlin, incidentally, was also Canadian. ]

[Other articles in category /book] permanent link

Thu, 03 Feb 2022Driving around today I passed by Mosaic Community Church. I first understood “mosaic” in the sense of colored tiles, but shortly after realized it is probably “Mosaic” (that is, pertaining to Moses) and not “mosaic”. But maybe not, perhaps it is an intentional double meaning, with “mosaic” meant to suggest a diverse congregation.

This got me thinking about words that completely change meaning when you capitalize them. The word “polish” came to mind.

I wondered if there were any other examples and realized there must be a great many boring ones of a certain type, which I confirmed when I got home: Pennsylvania has towns named Perry, Auburn, Potter, Bath, and so on. I think what makes “Polish” and “Mosaic” more interesting may be that their meanings are not proper nouns themselves but are derived adjectives.

[Other articles in category /lang] permanent link