Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | JFM |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 246 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 36 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 23 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Sun, 21 Sep 2025

My new git utility `what-changed-twice` needs a new name

As I have explained in the past, my typical workflow is to go

along commiting stuff that might or might not make sense, then clean it

all up at the end, doing multiple passes with git-add and git-rebase

to get related changes into the same commit, and then to order the

commits in a sensible way. Yesterday I built a new utility that I found

helpful. I couldn't think of a name for it, so I called it

what-changed-twice, which is not great but my I am bad at naming

things and my first attempt was analyze-commits. I welcome

suggestions. In this article I will call it Fred.

What is Fred for? I have a couple of uses for it so far.

Often as I work I'll produce a chain of commits that looks like this:

470947ff minor corrections

d630bf32 continue work on `jq` series

c24b8b24 wip

f4695e97 fix link

a8aa1a5c sp

5f1d7a61 WIP

a337696f Where is the quincunx on the quincunx?

39fe1810 new article: The fivefold symmetry of the quince

0a5a8e2e update broken link

196e7491 sp

bdc781f6 new article: fpuzhpx

40c52f47 merge old and new seasons articles and publish

b59441cd finish updating with Star Wars Droids

537a3545 droids and BJ and the Bear

d142598c Add nicely formatted season tables to this old article

19340470 mention numberphile video

It often happens that I will modify a file on Monday, modify it some more on Tuesday, correct a spelling error on Wednesday. I might have made 7 sets of changes to the main file, of which 4 are related, 2 others are related to each other but not to the other 4, and the last one is unrelated to any of the rest. When a file has changed more than once, I need to see what changed and then group the changes into related sets.

The sp commits are spelling corrections; if the error was made in the

same unmerged topic branch I will want to squash the correction into

the original commit so that the error never appears at all.

Some files changed only once, and I don't need to think about those at this stage. Later I can go back and split up those commits if it seems to make the history clearer.

Fred takes the output of git-log for the commits you are interested

in:

$ git log --stat -20 main...topic | /tmp/what-changed-twice

It finds which files were modified in which commits, and it prints a report about any file that was modified in more than one commit:

calendar/seasons.blog 196 40 d1

math/centrifuge.blog 193 33

misc/straight-men.blog 53 b5 bd

prog/jq-2.blog 33 5f d6

193 1934047

196 196e749

33 33a2304

40 40c52f4

53 537a354

5f 5f1d7a6

b5 b59441c

bd bdc781f

d1 d142598

d6 d630bf3

The report is in two parts. At the top, the path of each file that

changed more than once in the log, and the (highly-abbreviated) commit

IDs of the commits in which it changed. For example,

calendar/seasons.blog changed in commits 196, 40, and d1. The

second part of the report explains that 196 is actually an

abbreviation for commit 196e749.

Now I can look to see what else changed in those three commits:

$ git show --stat 196e749 40c52f4 d142598

then look at the changes to calendar/seasons.blog in those three

commits

$ git show 196e74 40c52f4 d142598 -- calendar/seasons.blog

and then decide if there are any changes I might like to squash together.

Many other files changed on the branch, but I only have to concern myself with four.

There's bonus information too. If a commit is not mentioned in the report, then it only changed files that didn't change in any other commit. That means that in a rebase, I can move that commit literally anywhere else in the sequence without creating a conflict. Only the commits in the report can cause conflicts if they are reordered.

I write most things in Python these days, but this one seemed to cry out for Perl. Here's the code.

Hmm, maybe I'll call it squash-what.

[Other articles in category /prog/git] permanent link

Sat, 16 Dec 2023

My Git pre-commit hook contained a footgun

The other day I made some changes to a program, but when I ran the tests they failed in a very bizarre way I couldn't understand. After a bit of investigation I still didn't understand. I decided to try to narrow down the scope of possible problems by reverting the code to the unmodified state, then introducing changes from one file at a time.

My plan was: commit all the new work, reset the working directory back to the last good commit, and then start pulling in file changes. So I typed in rapid succession:

git add -u

git commit -m 'broken'

git branch wat

git reset --hard good

So the complete broken code was on the new branch wat.

Then I wanted to pull in the first file from wat. But when I

examined wat there were no changes.

Wat.

I looked all around the history and couldn't find the changes. The

wat branch was there but it was on the current commit, the one with

none of the changes I wanted. I checked in the reflog for the commit

and didn't see it.

Eventually I looked back in my terminal history and discovered the

problem: I had a Git pre-commit hook which git-commit had

attempted to run before it made the new commit. It checks for strings

I don't usually intend to commit, such as XXX and the like.

This time one of the files had something like that. My pre-commit

hook had printed an error message and exited with a failure status, so

git-commit aborted without making the commit. But I had typed the

commands in quick succession without paying attention to what they

were saying, so I went ahead with the git-reset without even seeing

the error message. This wiped out the working tree changes that I had

wanted to preserve.

Fortunately the git-add had gone through, so the modified files were

in the repository anyway, just hard to find. And even more

fortunately, last time this happened to me, I wrote up

instructions about what to do.

This time around recovery was quicker and easier. I knew I only

needed to recover stuff from the last add command, so instead of

analyzing every loose object in the repository, I did

find .git/objects -mmin 10 --type f

to locate loose objects that had been modified in the last ten minutes. There were only half a dozen or so. I was able to recover the lost changes without too much trouble.

Looking back at that previous article, I see that it said:

it only took about twenty minutes… suppose that it had taken much longer, say forty minutes instead of twenty, to rescue the lost blobs from the repository. Would that extra twenty minutes have been time wasted? No! … The rescue might have cost twenty extra minutes, but if so it was paid back with forty minutes of additional Git expertise…

To that I would like to add, the time spent writing up the blog article was also well-spent, because it meant that seven years later I didn't have to figure everything out again, I just followed my own instructions from last time.

But there's a lesson here I'm still trying to figure out. Suppose I want to prevent this sort of error in the future. The obvious answer is “stop splatting stuff onto the terminal without paying attention, jackass”, but that strategy wasn't sufficient this time around and I couldn't think of any way to make it more likely to work next time around.

You have to play the hand you're dealt. If I can't fix myself, maybe I

can fix the software. I would like to make some changes to the

pre-commit hook to make it easier to recover from something like

this.

My first idea was that the hook could unconditionally save the staged changes somewhere before it started, and then once it was sure that it would complete it could throw away the saved changes. For example, it might use the stash for this.

(Although, strangely, git-stash does

not seem to have an easy way to say “stash the current changes, but

without removing them from the working tree”. Maybe git-stash save

followed by git-stash apply would do what I wanted? I have not yet

experimented with it.)

Rather than using the stash, the hook might just commit everything

(with commit -n to prevent infinite loops) and then reset the commit

immediately, before doing whatever it was planning to do. Then if it

was successful, Git would make a second, permanent commit and we could

forget about the one made by the hook. But if something went wrong,

the hook's commit would still be in the reflog. This doubles the

number of commits you make. That doesn't take much time, because Git

commit creation is lightning fast. But it would tend to clutter up

the reflog.

Thinking on it now, I wonder if a better approach isn't to turn the pre-commit hook into a post-commit hook. Instead of a pre-commit hook that does this:

- Check for errors in staged files

- If there are errors:

- Fix the files (if appropriate)

- Print a message

- Fail

- Otherwise:

- Exit successfully

- (

git-commitcontinues and commits the changes)

- If there are errors:

How about a post-commit hook that does this:

- Check for errors in the files that changed in the current head commit

- If there are errors:

- Soft-reset back to the previous commit

- Fix the files (if appropriate)

- Print a message

- Fail

- Otherwise:

- Exit successfully

- If there are errors:

Now suppose I ignore the failure, and throw away the staged changes. It's okay, the changes were still committed and the commit is still in the reflog. This seems clearly better than my earlier ideas.

I'll consider it further and report back if I actually do anything about this.

Larry Wall once said that too many programmers will have a problem, think of a solution, and implement it, but it works better if you can think of several solutions, then implement the one you think is best.

That's a lesson I think I have learned. Thanks, Larry.

Addendum

I see that Eric Raymond's version of the jargon file, last revised December 2003, omits “footgun”. Surely this word is not that new? I want to see if it was used on Usenet prior to that update, but Google Groups search is useless for this question. Does anyone have suggestions for how to proceed?

[Other articles in category /prog/git] permanent link

Mon, 27 Feb 2023

I wish people would stop insisting that Git branches are nothing but refs

I periodically write about Git, and sometimes I say something like:

Branches are named sequences of commits

and then a bunch of people show up and say “this is wrong, a branch is nothing but a ref”. This is true, but only in a very limited and unhelpful way. My description is a more useful approximation to the truth.

Git users think about branches and talk about branches. The Git documentation talks about branches and many of the commands mention branches. Pay attention to what experienced users say about branches while using Git, and it will be clear that they do not think of branches simply as just refs. In that sense, branches do exist: they are part of our mental model of how the repository works.

Are you a Git user who wants to argue about this? First ask yourself what we mean when we say “is your topic branch up to date?” “be sure to fetch the dev branch” “what branch did I do that work on?” “is that commit on the main branch or the dev branch?” “Has that work landed on the main branch?” “The history splits in two here, and the left branch is Alice's work but the right branch is Bob's”. None of these can be understood if you think that a branch is nothing but a ref. All of these examples show that when even the most sophisticated Git users talk about branches, they don't simply mean refs; they mean sequences of commits.

Here's an example from the official Git documentation, one of many: “If the upstream branch already contains a change you have made…”. There's no way to understand this if you insist that “branch” here means a ref or a single commit. The current Git documentation contains the word “branch” over 1400 times. Insisting that “a branch is nothing but a ref” is doing people disservice, because they are going to have to unlearn that in order to understand the documentation.

Some unusually dogmatic people might still argue that a branch is nothing but a ref. “All those people who say those things are wrong,” they might say, “even the Git documentation is wrong,” ignoring the fact that they also say those things. No, sorry, that is not the way language works. If someone claims that a true shoe is is really a Javanese dish of fried rice and fish cake, and that anyone who talks about putting shoes on their feet is confused or misguided, well, that person is just being silly.

The reason people say this, the disconnection is that the Git

software doesn't have any formal representation of branches.

Conceptually, the branch is there; the git commands just don't

understand it. This is the most important mismatch between the

conceptual model and what the Git software actually does.

Usually when a software model doesn't quite match its domain, we recognize that it's the software that is deficient. We say “the software doesn't represent that concept well” or “the way the software deals with that is kind of a hack”. We have a special technical term for it: it's a “leaky abstraction”. A “leaky abstraction” is when you ought to be able to ignore the underlying implementation, but the implementation doesn't reflect the model well enough, so you have to think about it more than you would like to.

When there's a leaky abstraction we don't normally try to pretend that the software's deficient model is actually correct, and that everyone in the world is confused. So why not just admit what's going on here? We all think about branches and talk about branches, but Git has a leaky abstraction for branches and doesn't handle branches very well. That's all, nothing unusual. Sometimes software isn't perfect.

When the Git software needs to deal with branches, it has to finesse

the issue somehow. For some commands, hardly any finesse is required.

When you do git log dev to get the history of the dev branch, Git

starts at the commit named dev and then works its way back, parent

by parent, to all the ancestor commits. For history logs, that's

exactly what you want! But Git never has to think of the branch as a

single entity; it just thinks of one commit at a time.

When you do git-merge, you might think you're merging two branches,

but again Git can finesse the issue. Git has to look at a little bit

of history to figure out a merge base, but after that it's not merging

two branches at all, it's merging two sets of changes.

In other cases Git uses a ref to indicate the end point of the branch (called the ‘tip’), and sorta infers the start point from context. For example, when you push a branch, you give the software a ref to indicate the end point of the branch, and it infers the start point: the first commit that the remote doesn't have already. When you rebase a branch, you give the software a ref to indicate the end point of the branch, and the software infers the start point, which is the merge-base of the start point and the upstream commit you're rebasing onto. Sometimes this inference goes awry and the software tries to rebase way more than you thought it would: Git's idea of the branch you're rebasing isn't what you expected. That doesn't mean it's right and you're wrong; it's just a miscommunication.

And sometimes the mismatch isn't well-disguised. If I'm looking at

some commit that was on a branch that was merged to master long ago,

what branch was that exactly? There's no way to know, if the ref was

deleted. (You can leave a note in the commit message, but that is not

conceptually different from leaving a post-it on your monitor.) The

best I can do is to start at the current master, work my way back in

history until I find the merge point, then study the other commits

that are on the same topic branch to try to figure out what was going

on. What if I merged some topic branch into master last week, other

work landed after that, and now I want to un-merge the topic? Sorry,

Git doesn't do that. And why not? Because the software doesn't

always understand branches in the way we might like. Not because the

question doesn't make sense, just because the software doesn't always

do what we want.

So yeah, the the software isn't as good as we might like. What software is? But to pretend that the software is right, and that all the defects are actually benefits is a little crazy. It's true that Git implements branches as refs, plus also a nebulous implicit part that varies from command to command. But that's an unfortunate implementation detail, not something we should be committed to.

[ Addendum 20230228: Several people have reminded me that the suggestions of the next-to-last paragraph are possible in some other VCSes, such as Mercurial. I meant to mention this, but forgot. Thanks for the reminder. ]

[Other articles in category /prog/git] permanent link

Wed, 06 Jul 2022

Things I wish everyone knew about Git (Part II)

This is a writeup of a talk I gave in December for my previous employer. It's long so I'm publishing it in several parts:

- Part I:

- Part II (you are here):

- More coming later:

- Branches are fictitious

- Committing partial changes

- Push and fetch; tracking branches

- Aliases and custom commands

The most important material is in Part I.

It is really hard to lose stuff

A Git repository is an append-only filesystem. You can add snapshots

of files and directories, but you can't modify or delete anything.

Git commands sometimes purport to modify data. For

example git commit --amend suggests that it amends a commit.

It doesn't. There is no such thing as amending a commit; commits are

immutable.

Rather, it writes a completely new commit, and then kinda turns its back on the old one. But the old commit is still in there, pristine, forever.

In a Git repository you can lose things, in the sense of forgetting

where they are. But they can almost always be found again, one way or

another, and when you find them they will be exactly the same as they

were before. If you git commit --amend and change your mind later,

it's not hard to get the old ⸢unamended⸣ commit back if you want it

for some reason.

If you have the SHA for a file, it will always be the exact same version of the file with the exact same contents.

If you have the SHA for a directory (a “tree” in Git jargon) it will always contain the exact same versions of the exact same files with the exact same names.

If you have the SHA for a commit, it will always contain the exact same metainformation (description, when made, by whom, etc.) and the exact same snapshot of the entire file tree.

Objects can have other names and descriptions that come and go, but the SHA is forever.

(There's a small qualification to this: if the SHA is the only way to refer to a certain object, if it has no other names, and if you haven't used it for a few months, Git might discard it from the repository entirely.)

But what if you do lose something?

There are many good answers to this question but I think the one to

know first is git-reflog, because it covers the great majority of

cases.

The git-reflog command means:

“List the SHAs of commits I have visited recently”

When I run git reflog the top of the output says what commits I

had checked out at recently, with the top line being the commit I have checked

out right now:

523e9fa1 HEAD@{0}: checkout: moving from dev to pasha

5c31648d HEAD@{1}: pull: Fast-forward

07053923 HEAD@{2}: checkout: moving from pr2323 to dev

...

The last thing I did was check out the branch named pasha; its tip

commit is at 523e9f1a.

Before

that, I did git pull and Git updated my local dev branch from the

remote one, updating it to 5c31648d.

Before that, I had switched to dev from a different branch,

pr2323. At that time, before the pull, dev referred to commit

07053923.

Farther down in the output are some commits I visited last August:

...

58ec94f6 HEAD@{928}: pull --rebase origin dev: checkout 58ec94f6d6cb375e09e29a7a6f904e3b3c552772

e0cfbaee HEAD@{929}: commit: WIP: model classes for condensedPlate and condensedRNAPlate

f8d17671 HEAD@{930}: commit: Unskip tests that depend on standard seed data

31137c90 HEAD@{931}: commit (amend): migrate pedigree tests into test/pedigree

a4a2431a HEAD@{932}: commit: migrate pedigree tests into test/pedigree

1fe585cb HEAD@{933}: checkout: moving from LAB-808-dao-transaction-test-mode to LAB-815-pedigree-extensions

...

Suppose I'm caught in some horrible Git nightmare. Maybe I deleted the entire test suite or accidentally put my Small Wonder fanfic into a commit message or overwrote the report templates with 150 gigabytes of goat porn. I can go back to how things were before. I look in the reflog for the SHA of the commit just before I made my big blunder, and then:

git reset --hard 881f53fa

Phew, it was just a bad dream.

(Of course, if my colleagues actually saw the goat porn, it can't fix that.)

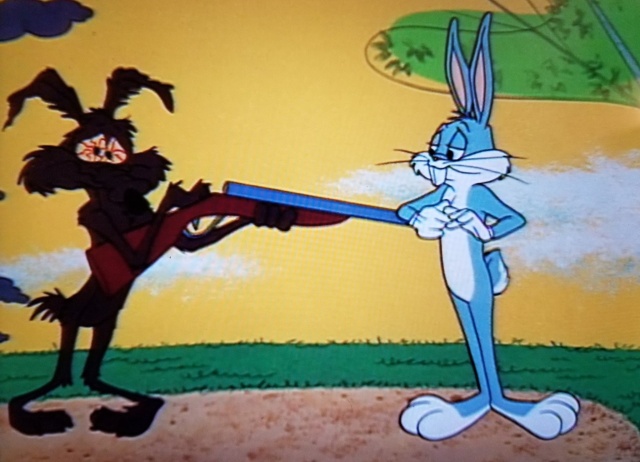

I would like to nominate Wile E. Coyote to be the mascot of Git. Because Wile E. is always getting himself into situations like this one:

But then, in the next scene, he is magically unharmed. That's Git.

Finding old stuff with git-reflog

git reflogby itself lists the places thatHEADhas beengit reflog some-branchlists the places thatsome-branchhas been- That

HEAD@{1}thing in thereflogoutput is another way to name that commit if you don't want to use the SHA. - You can abbreviate it to just

@{1}. The following locutions can be used with any git command that wants you to identify a commit:

@{17}(HEADas it was 17 actions ago)@{18:43}(HEADas it was at 18:43 today)@{yesterday}(HEADas it was 24 hours ago)dev@{'3 days ago'}(devas it was 3 days ago)some-branch@{'Aug 22'}(some-branchas it was last August 22)

(Use with

git-checkout,git-reset,git-show,git-diff, etc.)Also useful:

git show dev@{'Aug 22'}:path/to/some/file.txt“Print out that file, as it was on

dev, asdevwas on August 22”

It's all still in there.

What if you can't find it?

Don't panic! Someone with more experience can probably find it for you. If you have a local Git expert, ask them for help.

And if they are busy and can't help you immediately, the thing you're looking for won't disappear while you wait for them. The repository is append-only. Every version of everything is saved. If they could have found it today, they will still be able to find it tomorrow.

(Git will eventually throw away lost and unused snapshots, but typically not anything you have used in the last 90 days.)

What if you regret something you did?

Don't panic! It can probably put it back the way it was.

Git leaves a trail

When you make a commit, Git prints something like this:

your-topic-branch 4e86fa23 Rework foozle subsystem

If you need to find that commit again, the SHA 4e86fa23 is in your

terminal scrollback.

When you fetch a remote branch, Git prints:

6e8fab43..bea7535b dev -> origin/dev

What commit was origin/dev before the fetch? At 6e8fab43.

What commit is it now? bea7535b.

What if you want to look at how it was before? No problem, 6e8fab43

is still there. It's not called origin/dev any more, but the SHA is

forever. You can still check it out and look at it:

git checkout -b how-it-was-before 6e8fab43

What if you want to compare how it was with how it is now?

git log 6e8fab43..bea7535b

git show 6e8fab43..bea7535b

git diff 6e8fab43..bea7535b

Git tries to leave a trail of breadcrumbs in your terminal. It's constantly printing out SHAs that you might want again.

A few things can be lost forever!

After all that talk about how Git will not lose things, I should point

out the exceptions. The big exception is that if you have created

files or made changes in the working tree, Git is unaware of them

until you have added them with git-add. Until then, those changes

are in the working tree but not in the repository, and if you discard

them Git cannot help you get them back.

Good advice is Commit early and often. If you don't commit, at

least add changes with git-add. Files added but not committed are

saved in the repository,

although they can be hard to find

because they haven't been packaged into a commit with a single SHA id.

Some people automate this: they have a process that runs every few minutes and commits the current working tree to a special branch that they look at only in case of disaster.

The dangerous commands are

git-resetandgit-checkout

which modify the working tree, and so might wipe out changes that aren't in the repository. Git will try to warn you before doing something destructive to your working tree changes.

git-rev-parse

We saw a little while ago that Git's language for talking about commits and files is quite sophisticated:

my-topic-branch@{'Aug 22'}:path/to/some/file.txt

Where is this language documented? Maybe not where you would expect: it's in the

manual for git-rev-parse.

The git rev-parse command is less well-known than it should be. It takes a

description of some object and turns it into a SHA.

Why is that useful? Maybe not, but

The

git-rev-parseman page explains the syntax of the descriptions Git understands.

A good habit is to skim over the manual every few months. You'll pick up something new and useful every time.

My favorite is that if you use the syntax :/foozle you get the most

recent commit on the current branch whose message mentions

foozle. For example:

git show :/foozle

or

git log :/introduce..:/remove

Coming next week (probably), a few miscellaneous matters about using Git more effectively.

[Other articles in category /prog/git] permanent link

Wed, 29 Jun 2022

Things I wish everyone knew about Git (Part I)

This is a writeup of a talk I gave in December for my previous employer. It's long so I'm publishing it in several parts:

- Part I (you are here):

- Part II: (coming later)

- More coming later still:

- Branches are fictitious

- Committing partial changes

- Push and fetch; tracking branches

- Aliases and custom commands

How to approach Git; general strategy

Git has an elegant and powerful underlying model based on a few simple concepts:

- Commits are immutable snapshots of the repository

- Branches are named sequences of commits

- Every object has a unique ID, derived from its content

Built atop this elegant system is a flaming trash pile.

The command set wasn't always well thought out, and then over the years it grew by accretion, with new stuff piled on top of old stuff that couldn't be changed because Backward Compatibility. The commands are non-orthogonal and when two commands perform the same task they often have inconsistent options or are described with different terminology. Even when the individual commands don't conflict with one another, they are often badly-designed and confusing. The documentation is often very poorly written.

What this means

With a lot of software, you can opt to use it at a surface level without understanding it at a deeper level:

“I don't need to

know how it works.

I just want to know which commands to run.”

This is often an effective strategy, but

with Git, this does not work.

You can't “just know which commands to run” because the commands do not make sense!

To work effectively with Git, you must have a model of what the repository is like, so that you can formulate questions like “is the repo on this state or that state?” and “the repo is in this state, how do I get it into that state?”. At that point you look around for a command that answers your question, and there are probably several ways to do what you want.

But if you try to understand the commands without the model, you will suffer, because the commands do not make sense.

Just a few examples:

git-resetdoes up to three different things, depending on flagsgit-checkoutis worseThe opposite of

git-pushis notgit-pull, it'sgit-fetchetc.

If you try to understand the commands without a clear idea of the model, you'll be perpetually confused about what is happening and why, and you won't know what questions to ask to find out what is going on.

READ THIS

When I first used Git it drove me almost to tears of rage and frustration. But I did get it under control. I don't love Git, but I use it every day, by choice, and I use it effectively.

The magic key that rescued me was

John Wiegley's

Git From the

Bottom Up

Git From the Bottom Up explains the model. I read it. After that I wept no more. I understood what was going on. I knew how to try things out and how to interpret what I saw. Even when I got a surprise, I had a model to fit it into.

That's the best advice I have. Read Wiegley's explanation. Set aside time to go over it carefully and try out his examples. It fixed me.

If I were going to tell every programmer just one thing about Git, that would be it.

The rest of this series is all downhill from here.

But if I were going to tell everyone just one more thing, it would be:

It is very hard to

permanently lose work.

If something seems to have gone wrong, don't panic.

Remain calm and ask an expert.

Many more details about that are in the followup article.

[Other articles in category /prog/git] permanent link

Wed, 31 Dec 1969I often write about Git but the Git articles are mixed in with everything else. Someday I will rearrange everything. In the meantime I will try to keep a list of links on this page.

- Another Git catastrophe cleaned up

- Another trivial utility:

git-q - Automatically checking for syntax errors with Git's

pre-commithook git log --author=...confused megit log --followenthusiastically tracks empty files- And what happened when I tried to fix this: Perils of hacking on mature software

- Git PSA:

git-rev-parse - Git remote branches and Git's missing terminology

- Git wishlist: aggregate changes across non-contiguous commits

- Git's rejected push error

- A hack for getting the email address Git will use for a commit

- Hacking the

gitshell prompt - How I got four errors into a one-line program (

prepare-commit-hook)) - How to recover lost files added to Git but not committed

- I wish people would stop insisting that Git branches are nothing but refs

- Notes on using

git-replaceto get rid of giant objects - Reordering git commits (not patches) with interactive rebase

- Reordering git commits with

git-commit-tree - Rewriting published history in Git

- Things I wish everyone knew about Git:

- Srtst vrsn: Two things everyone should know about Git

- Part I: General strategy and READ THIS

- Part II: It's hard to lose stuff and if you do you can find it again

- Part III: Misc (Branches are fictitious, committing partial changes; push and fetch; tracking branches)

- Why didn't

git add -pwork?

[Other articles in category /prog/git] permanent link