Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | J |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Thu, 22 Aug 2024

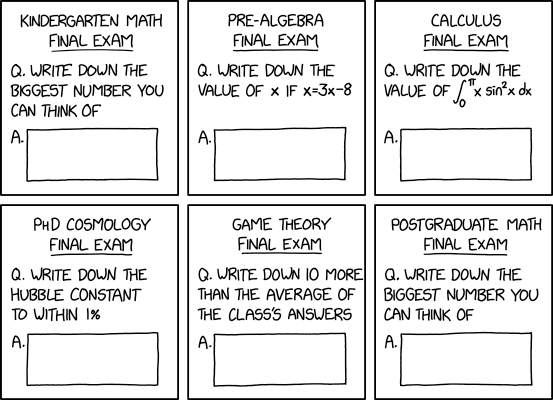

(Source: XKCD “Exam numbers”.)

This post is about the bottom center panel, “Game Theory final exam”.

I don't know much about game theory and I haven't seen any other discussion of this question. But I have a strategy I think is plausible and I'm somewhat pleased with.

(I assume that answers to the exam question must be real numbers — not !!\infty!! — and that “average” here is short for 'arithmetic mean'.)

First, I believe the other players and I must find a way to agree on what the average will be, or else we are all doomed. We can't communicate, so we should choose a Schelling point and hope that everyone else chooses the same one. Fortunately, there is only one distinguished choice: zero. So I will try to make the average zero and I will hope that others are trying to do the same.

If we succeed in doing this, any winning entry will therefore be !!10!!. Not all !!n!! players can win because the average must be !!0!!. But !!n-1!! can win, if the one other player writes !!-10(n-1)!!. So my job is to decide whether I will be the loser. I should select a random integer between !!0!! and !!n-1!!. If it is zero, I have drawn a short straw, and will write !!-10(n-1)!!. otherwise I write !!10!!.

(The straw-drawing analogy is perhaps misleading. Normally, exactly one straw is short. Here, any or all of the straws might be short.)

If everyone follows this strategy, then I will win if exactly one person draws a short straw and if that one person isn't me. The former has a probability that rapidly approaches !!\frac1e\approx 36.8\%!! as !!n!! increases, and the latter is !!\frac{n-1}n!!. In an !!n!!-person class, the probability of my winning is $$\left(\frac{n-1}n\right)^n$$ which is already better than !!\frac13!! when !!n= 6!!, and it increases slowly toward !!36.8\%!! after that.

Some miscellaneous thoughts:

The whole thing depends on my idea that everyone will agree on !!0!! as a Schelling point. Is that even how Schelling points work? Maybe I don't understand Schelling points.

I like that the probability !!\frac1e!! appears. It's surprising how often this comes up, often when multiple agents try to coordinate without communicating. For example, in ALOHAnet a number of ground stations independently try to send packets to a single satellite transceiver, but if more than one tries to send a packet at a particular time, the packets are garbled and must be retransmitted. At most !!\frac1e!! of the available bandwidth can be used, the rest being lost to packet collisions.

The first strategy I thought of was plausible but worse: flip a coin, and write down !!10!! if it is heads and !!-10!! if it is tails. With this strategy I win if exactly !!\frac n2!! of the class flips heads and if I do too. The probability of this happening is only $$\frac{n\choose n/2}{2^n}\cdot \frac12 \approx \frac1{\sqrt{2\pi n}}.$$ Unlike the other strategy, this decreases to zero as !!n!! increases, and in no case is it better than the first strategy. It also fails badly if the class contains an odd number of people.

Thanks to Brian Lee for figuring out the asymptotic value of !!4^{-n}\binom{2n}{n}!! so I didn't have to.

Just because this was the best strategy I could think of in no way means that it is the best there is. There might have been something much smarter that I did not think of, and if there is then my strategy will sabotage everyone else.

Game theorists do think of all sorts of weird strategies that you wouldn't expect could exist. I wrote an article about one a few years back.

Going in the other direction, even if !!n-1!! of the smartest people all agree on the smartest possible strategy, if the !!n!!th person is Leeroy Jenkins, he is going to ruin it for everyone.

If I were grading this exam, I might give full marks to anyone who wrote down either !!10!! or !!-10(n-1)!!, even if the average came out to something else.

For a similar and also interesting but less slippery question, see Wikipedia's article on Guess ⅔ of the average. Much of the discussion there is directly relevant. For example, “For Nash equilibrium to be played, players would need to assume both that everyone else is rational and that there is common knowledge of rationality. However, this is a strong assumption.” LEEROY JENKINS!!

People sometimes suggest that the real Schelling point is for everyone to write !!\infty!!. (Or perhaps !!-\infty!!.)

Feh.

If the class knows ahead of time what the question will be, the strategy becomes a great deal more complicated! Say there are six students. At most five of them can win. So they get together and draw straws to see who will make a sacrifice for the common good. Vidkun gets the (unique) short straw, and agrees to write !!-50!!. The others accordingly write !!10!!, but they discover that instead of !!-50!!, Vidkun has written !!22!! and is the only person to have guessed correctly.

I would be interested to learn if there is a playable Nash equilibrium under these circumstances. It might be that the optimal strategy is for everyone to play as if they didn't know what the question was beforehand!

Suppose the players agree to follow the strategy I outlined, each rolling a die and writing !!-50!! with probability !!\frac16!!, and !!10!! otherwise. And suppose that although the others do this, Vidkun skips the die roll and unconditionally writes !!10!!. As before, !!n-1!! players (including Vidkun) win if exactly one of them rolls zero. Vidkun's chance of winning increases. Intuitively, the other players' chances of winning ought to decrease. But by how much? I think I keep messing up the calculation because I keep getting zero. If this were actually correct, it would be a fascinating paradox!

[Other articles in category /math] permanent link