Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | J |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Sun, 25 May 2025

Mystery of the quincunx's missing quincunx

A quincunx is the X-shaped pattern of pips on the #5 face of a die.

It's so-called because the Romans had a common copper coin called an as, and it was divided (monetarily, not physically) into twelve uncia. There was a bronze coin worth five uncia called a quīncunx, which is a contraction of quīnque (“five”) + uncia, and the coin had that pattern of dots on it to indicate its value.

Uncia generally meant a twelfth of something. It was not just a twelfth of an as, but also a twelfth of a pound , which is where we get the word “ounce”, and a twelfth of a foot, which is where we get the word “inch”.

The story I always heard about the connection between the coin and the X-shaped pattern of dots was the one that is told by Wikipedia:

Its value was sometimes represented by a pattern of five dots arranged at the corners and the center of a square, like the pips of a die. So, this pattern also came to be called quincunx.

Or the Big Dictionary:

… [from a] coin of this value (occasionally marked with a pattern resembling the five spots on a dice cube),…

But today I did Google image search for qunicunxes. And while most had five dots, I found not even one that had the dots arranged in an X pattern.

(I believe the heads here are Minerva, goddess of wisdom. The owl is also associated with Minerva.)

Where's the quincunx that actually has a quincuncial arrangement of dots? Nowhere to be found, it seems. But everyone says it, so it must be true.

Addenda

The first common use of “quincunx” as an English word was to refer to trees that were planted in a quincuncial pattern, although not necessarily in groups of exactly five, in which each square of four trees had a fifth at its center.

Similarly, the Galton Box, has a quincuncial arrangement of little pegs. Galton himself called it a “quincunx”.

The OED also offers this fascinating aside:

Latin quincunx occurs earlier in an English context. Compare the following use apparently with reference to a v-shaped figure:

1545 Decusis, tenne hole partes or ten Asses...It is also a fourme in any thynge representyng the letter, X, whiche parted in the middel, maketh an other figure called Quincunx, V.

which shows that for someone, a quincuncial shape was a V and not an X, presumably because V is the Roman numeral for five.

A decussis was a coin worth not ten uncia but ten asses, and it did indeed have an X on the front. A five-as coin was a quincussis and it had a V. I wonder if the author was confused?

The source is Bibliotheca Eliotæ. The OED does not provide a page number.

It wasn't until after I published this that I realized that today's date was the extremely quincuncial 2025-05-25. I thank the gods of chance and fortune for this little gift.

[Other articles in category /history] permanent link

Sat, 06 May 2023A “pillar box” is a British mailbox. It usually has the monogram (“cypher”) of the reigning monarch at the time it was built. At right are two examples. The one to the right has the monogram of Queen Elizabeth II, also depicted below.

(“EⅡR” is short for “Elizabeth II Regina”). The pillar box to the left has the monogram of her father, George VI.

When Elizabeth was crowned in 1953, there was a dispute in Scotland over what she should be called. “Elizabeth II of Scotland” was a bit of an oddity because Scotland had never before had a queen named Elizabeth: England's Elizabeth I had never been queen of Scotland, which at the time was a separate kingdom. Compare the so-called James VI and I who was King James VI of Scotland but King James I of England. (He was the son of Elizabeth's cousin Mary. James I–V had been the kings of Scotland from 1406–1542.)

Post boxes in Scotland with Elizabeth's “EⅡR” monogram were repeatedly vandalized and in some cases exploded. A lawsuit was filed in Scotland, asserting that the proclamation of Elizabeth II was a violation of the 1707 Act of union between England and Scotland. The court disagreed: “The [Act of Union] did not contain any provision as to the style and titles to be adopted by the monarch of the new [United] kingdom.” The plaintiff was required to pay the respondent's legal expenses.

The two nations found an acceptable compromise: after 1953 pillar boxes erected in Scotland omitted Elizabeth's monogram entirely, and included only a heraldic representation of the crown of Scotland.

The issue doesn't come up with Charles III, who is the third monarch of that name in both England and Scotland.

Pillar box photograph by Kitmaster is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Elizabeth II's royal cypher by Sodacan is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

[Other articles in category /history] permanent link

Mon, 31 Oct 2022Content warning: something here to offend almost everyone

A while back I complained that there were no emoji portraits of U.S. presidents. Not that there a Chester A. Arthur portrait would see a lot of use. But some of the others might come in handy.

I couldn't figure them all out. I have no idea what a Chester Arthur emoji would look like. And I assigned 🧔🏻 to all three of Garfield, Harrison, and Hayes, which I guess is ambiguous but do you really need to be able to tell the difference between Garfield, Harrison, and Hayes? I don't think you do. But I'm pretty happy with most of the rest.

| George Washington | 💵 |

| John Adams | |

| Thomas Jefferson | 📜 |

| James Madison | |

| James Monroe | |

| John Quincy Adams | 🍐 |

| Andrew Jackson | |

| Martin Van Buren | 🌷 |

| William Henry Harrison | 🪦 |

| John Tyler | |

| James K. Polk | |

| Zachary Taylor | |

| Millard Fillmore | ⛽ |

| Franklin Pierce | |

| James Buchanan | |

| Abraham Lincoln | 🎭 |

| Andrew Johnson | 💩 |

| Ulysses S. Grant | 🍸 |

| Rutherford B. Hayes | 🧔🏻 |

| James Garfield | 🧔🏻 |

| Chester A. Arthur | |

| Grover Cleveland | 🔂 |

| Benjamin Harrison | 🧔🏻 |

| Grover Cleveland | 🔂 |

| William McKinley | |

| Theodore Roosevelt | 🧸 |

| William Howard Taft | 🛁 |

| Woodrow Wilson | 🎓 |

| Warren G. Harding | 🫖 |

| Calvin Coolidge | 🙊 |

| Herbert Hoover | ⛺ |

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | 👨🦽 |

| Harry S. Truman | 🍄 |

| Dwight D. Eisenhower | 🪖 |

| John F. Kennedy | 🍆 |

| Lyndon B. Johnson | 🗳️ |

| Richard M. Nixon | 🐛 |

| Gerald R. Ford | 🏈 |

| Jimmy Carter | 🥜 |

| Ronald Reagan | 💸 |

| George H. W. Bush | 👻 |

| William J. Clinton | 🎷 |

| George W. Bush | 👞 |

| Barack Obama | 🇰🇪 |

| Donald J. Trump | 🍊 |

| Joseph R. Biden | 🕶️ |

Honorable mention: Benjamin Franklin 🪁

Dishonorable mention: J. Edgar Hoover 👚

If anyone has better suggestions I'm glad to hear them. Note that I considered, and rejected 🎩 for Lincoln because it doesn't look like his actual hat. And I thought maybe McKinley should be 🏔️ but since they changed the name of the mountain back I decided to save it in case we ever elect a President Denali.

(Thanks to Liam Damewood for suggesting Harding, and to Colton Jang for Clinton's saxophone.)

Addenda

20221106

Twitter user Simon suggests emoji for UK prime ministers.

20221108

Rasmus Villemoes makes a good suggestion of 😼 for Garfield. I had considered this angle, but abandoned it because there was no way to be sure that the cat would be orange, overweight, or grouchy. Also the 🧔🏻 thing is funnier the more it is used. But I had been unaware that there is CAT FACE WITH WRY SMILE until M. Villemoes brought it to my attention, so maybe. (Had there been an emoji resembling a lasagna I would have chosen it instantly.)

20221108

January First-of-May has suggested 🌷 for Maarten van Buren, a Dutch-American whose first language was not English but Dutch. Let it be so!

20221218

Lorrie Kim reminded me that an old friend of ours, a former inhabitant of New Orleans, used to pass through Jackson Square, see the big statue of Andrew Jackson, and reflect gleefully on how he was covered in pigeon droppings. Lorrie suggested that I add a pigeon to the list above.

However, while there is a generic "bird" emoji, it is not specifically a pigeon. There are also three kinds of baby chicks; chickens both male and female; doves, ducks, eagles, flamingos, owls, parrots, peacocks, penguins, swans and turkeys; also single eggs and nests with multiple eggs. But no pigeons.

20250205

I got Anthropic's LLM, Claude, to help me with these, and it had some excellent suggestions.

[Other articles in category /history] permanent link

Mon, 04 Apr 2022If you're losing the game, try instead playing the different game that is one level up.

I remembered a wonderful example of this: The Chen Sheng and Wu Guang Uprising of 209 BCE. As Wikipedia tells it:

[Chen Sheng] was a military captain along with Wu Guang when the two of them were ordered to lead 900 soldiers to Yuyang to help defend the northern border against Xiongnu. Due to storms, it became clear that they could not get to Yuyang by the deadline, and according to law, if soldiers could not get to their posts on time, they would be executed. Chen Sheng and Wu Guang, believing that they were doomed, led their soldiers to start a rebellion.

The uprising was ultimately unsuccessful, but it at least bought Chen Sheng and Wu Guang some time.

[Other articles in category /history] permanent link

Tue, 02 Jul 2019

Philadelphia Slaughterhouse Hotel

More information about the mysterious slaughterhouse hotel has come to light, thanks to Chas. Owens, Pete Krawczyk, and this useful blog post by D.S. Rosenstein.

Most important, the perplexing “hotel” is not intended for humans. “Hotel” is apparently stockyard jargon for a place where livestock are quartered temporarily just prior to slaughter. I am so glad to have this cleared up.

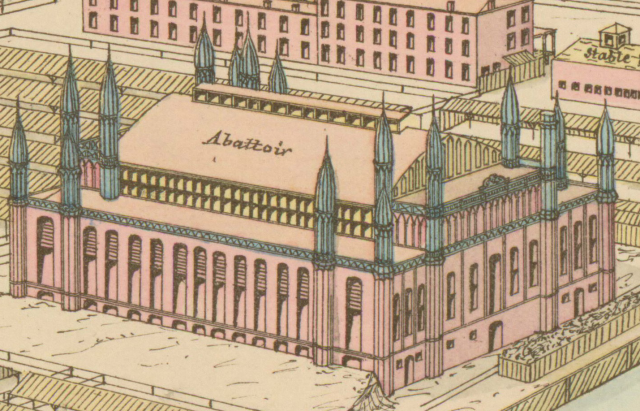

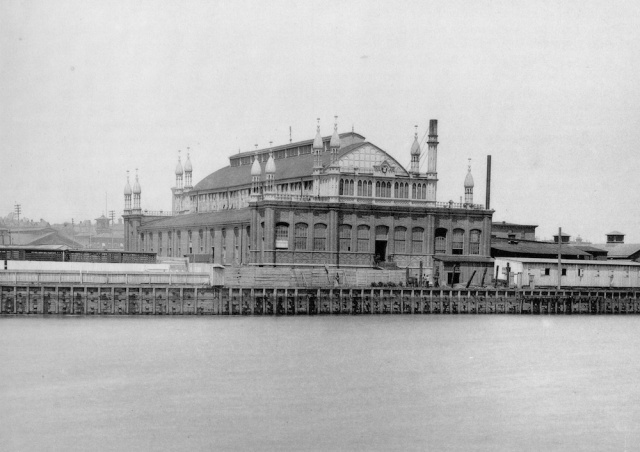

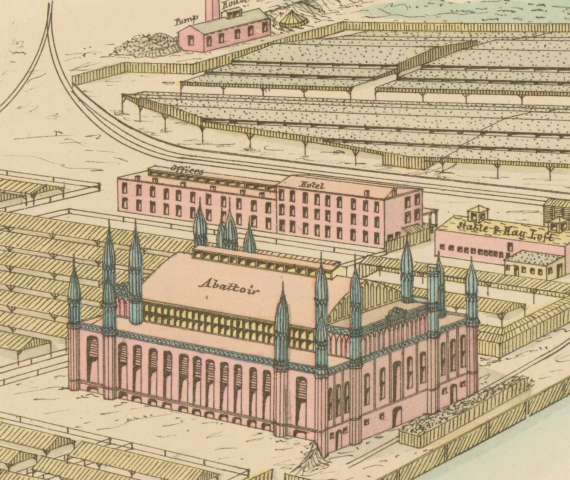

Also, M. Rosenstein has a photograph of the fancy abattoir with the spires:

They don't make industrial buildings like they used to. Check out the ornamental pattern in the bricks on the lower floor and the baluster along the riverside façade.

[ Addendum: Josh Bevan of Hidden City Philadelphia on When Cattle Men Reigned In The West (of Philadelphia). ]

[Other articles in category /history] permanent link

Mon, 01 Jul 2019

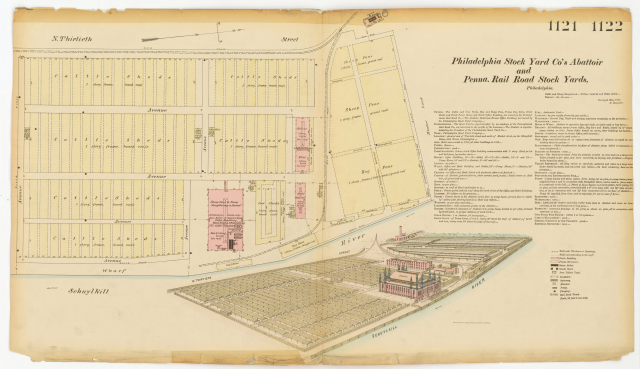

Philadelphia Slaughterhouse Hotel

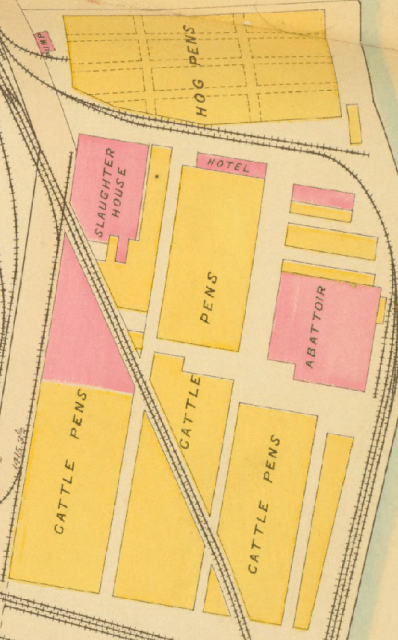

Yesterday on my other blog I posted about the most hilariously mislocated hotel I've ever heard of. It's the hotel that in 1910 was located in the Philadelphia stockyards, just the other side of the railroad tracks from the hog pens, between the slaughter house and the abbatoir:

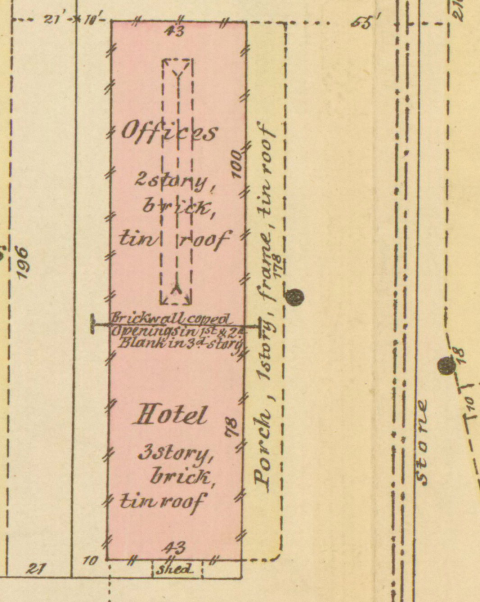

I thought that would be the end of it, but Chas. Owens did a little digging around and found a picture of the hotel, provided by the Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network. It's from R. Hexamer's insurance survey of 1877. At that time, the building was partly a hotel and partly the offices of the Philadelphia Stock Yard Company.

The survey includes a map of the site and a description of the facilities. Here's the detailed plan of the hotel:

The full image is 105 MB:

None of these buildings is still standing. (As I mentioned yesterday, the site is now occupied by the Cira Centre.) But the neighborhood's history as the center of Philadelphia's meatpacking district is not completely lost. According to this marvelous article from Hidden City Philadelphia, in 1906 the D.B. Martin company built a new combination office building and slaughterhouse only two blocks away at 3000 Market Street. Here's my favorite detail from the article:

Five hundred head of cattle at a time would be held on the rooftop cow pens, right above the heads of the company’s executives,

That building still stands, although I believe it's no longer used as a slaughterhouse.

[ Addendum 20190702: The “hotel” is explained: it is a temporary residence for livestock, not for humans. ]

[Other articles in category /history] permanent link

Tue, 23 Oct 2018A few years back I asked on history stackexchange:

Wikipedia's article on the Halifax Gibbet says, with several citations:

…ancient custom and law gave the Lord of the Manor the authority to execute summarily by decapitation any thief caught with stolen goods to the value of 13½d or more…

My question being: why 13½ pence?

This immediately attracted an answer that was no good at all. The author began by giving up:

This question is historically unanswerable.

I've met this guy and probably you have too: he knows everything worth knowing, and therefore what he doesn't know must be completely beyond the reach of mortal ken. But that doesn't mean he will shrug and leave it at that, oh no. Having said nobody could possibly know, he will nevertheless ramble for six or seven decreasingly relevant paragraphs, as he did here.

45 months later, however, a concise and pertinent answer was given by Aaron Brick:

13½d is a historical value called a loonslate. According to William Hone, it has a Scottish origin, being two-thirds of the Scottish pound, as the mark was two-thirds of the English pound. The same value was proposed as coinage for South Carolina in 1700.

This answer makes me happy in several ways, most of them positive. I'm glad to have a lead for where the 13½ pence comes from. I'm glad to learn the odd word “loonslate”. And I'm glad to be introduced to the bizarre world of pre-union Scottish currency, which, in addition to the loonslate, includes the bawbee, the unicorn, the hardhead, the bodle, and the plack.

My pleasure has a bit of evil spice in it too. That fatuous claim that the question was “historically unanswerable” had been bothering me for years, and M. Brick's slam-dunk put it right where it deserved.

I'm still not completely satisfied. The Scottish mark was worth ⅔ of a pound Scots, and the pound Scots, like the English one, was divided not into 12 pence but into 20 shillings of 12 pence each, so that a Scottish mark was worth 160d, not 13½d. Brick cites William Hone, who claims that the pound Scots was divided into twelve pence, rather than twenty shillings, so that a mark was worth 13⅔ pence, but I can't find any other source that agrees with him. Confusing the issue is that starting under the reign of James VI and I in 1606, the Scottish pound was converted to the English at a rate of twelve-to-one, so that a Scottish mark would indeed have been convertible to 13⅔ English pence, except that the English didn't denominate pence in thirds, so perhaps it was legally rounded down to 13½ pence. But this would all have been long after the establishment of the 13½d in the Halifax gibbet law and so unrelated to it.

Or would it? Maybe the 13½d entered popular consciousness in the 17th century, acquired the evocative slang name “hangman’s wages”, and then an urban legend arose about it being the cutoff amount for the Halifax gibbet, long after the gibbet itself was dismantled arond 1650. I haven't found any really convincing connection between the 13½d and the gibbet that dates earlier than 1712. The appearance of the 13½d in the gibbet law could be entirely the invention of Samuel Midgley.

I may dig into this some more. The 1771 Encyclopædia Britannica has a 16-page article on “Money” that I can look at. I may not find out what I want to know, but I will probably find out something.

[Other articles in category /history] permanent link

Thu, 18 Jan 2018In autumn 2014 I paid for something and got $15.33 in change. I thought I'd take the hint from the Universe and read Wikipedia's article on the year 1533. This turned out unexpectedly exciting. 1533 was a big year in English history. Here are the highlights:

- January 25: King Henry VIII marries Anne Boleyn

- March 30: Thomas Cranmer becomes Archbishop of Canterbury

- May 23: Cranmer annuls Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon

- June 1: Boleyn crowned queen consort by Cranmer

- July 11: Henry excommunicated by Pope Clement VII

- September 7: Princess Elizabeth, later Queen Elizabeth I, is born to Boleyn

A story clearly emerges here, the story of Henry's frantic response to Anne Boleyn's surprise pregnancy.

The first thing to notice is that Elizabeth was born only seven months after Henry married Boleyn. The next thing to notice is that Henry was still married to Catherine when he married Boleyn. He had to get Cranmer to annul the marriage, issuing a retroactive decree that not only was Henry not married to Catherine, but he had never been married to her.

In 2014 I imagined that Henry appointed Cranmer to be Archbishop on condition that he get the annulment, and eventually decided that was not the case. Looking at it now, I'm not sure why I decided that.

While Cranmer was following Charles through Italy, he received a royal letter dated 1 October 1532 informing him that he had been appointed the new Archbishop of Canterbury, following the death of archbishop William Warham [on 22 August]. Cranmer was ordered to return to England. The appointment had been secured by the family of Anne Boleyn, who was being courted by Henry.

Cranmer had been working on that annulment since at least 1527. In 1532 he was ambassador to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, who was the nephew of Henry's current wife Catherine. I suppose a large part of Cranmer's job was trying to persuade Charles to support the annulment. (He was unsuccessful.) When Charles conveniently went to Rome (what for? Wikipedia doesn't say) Cranmer followed him and tried to drum up support there for the annulment. (He was unsuccessful in that too.)

Fortunately there was a convenient vacancy, and Henry called him back to fill it, and got his annulment that way. In 2014 I thought Warham's death was just a little too convenient, but I decided that he died too early for it to have been arranged by Henry. Now I'm less sure — Henry was certainly capable of such cold-blooded planning — but I can't find any mention of foul play, and The Divorce of Henry VIII: The Untold Story from Inside the Vatican describes the death as “convenient though entirely natural”.

[ Addendum: This article used to say that Elizabeth was born “less than seven months” after Henry and Boleyn's marriage. Daniel Holtz has pointed out that this was wrong. The exact amount is 225 days, or 32 weeks plus one day. The management regrets the error. ]

[Other articles in category /history] permanent link