Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2025: | JFMAM |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 99 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 15 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Tue, 18 Mar 2025

We want to adapt baseball to be played on the moon. Is there any way to make it work?

My first impression is: no, for several reasons.

The pitched ball will go a little faster (no air resistance) but breaking balls are impossible (ditto). So the batter will find it easier to get a solid hit. We can't fix this by moving the plate closer to the pitcher's rubber; that would expose both batter and pitcher to unacceptable danger. I think we also can't fix it by making the plate much wider.

Once the batter hits the ball, it will go a long long way, six times as far as a batted ball on Earth. In order for every hit to not be a home run, the outfield fence will have to be about six times as far way, so the outfield will be !!36!! times as large. I don't think the outfielders can move six times as fast to catch up to it. Perhaps if there were 100 outfielders instead of only three?

Fielding the ball will be more difficult. Note that even though the vacuum prevents the pitch from breaking, the batted ball can still take unexpected hops off the ground.

Having gotten hold of the ball, the outfielder will then need to throw it back to the infield. They will be able to throw it that far, but they probably won't be able do it accurately enough for the receiving fielder to make the play at the base. More likely the outfielder will throw it wild.

I don't think this can be easily salvaged. People do love home runs, but I don't think they would love this. Games are too long already.

Well, here's a thought. What if instead of four bases, arranged in a !!90!!-foot square, we had, I don't know, eight or ten, maybe !!200!! or !!300!! feet apart? More opportunities for outs on the basepaths, and also the middle bases would not be so far from the outfield. Instead of throwing directly to the infield, the outfielders would have a relay system where one outfielder would throw to another that was farther in, and perhaps one more, before reaching the infield. That might be pretty cool.

I think it's not easy to run fast on the Moon. On the Earth, a runner's feet are pushing against the ground many times each second. On the Moon, the runner is taking big leaps. They may only get in one-sixth as many steps over the same distance, which would give them much less opportunity to convert muscle energy into velocity. (Somewhat countervailing, though: no air resistance.) Runners would have to train specially to be able to leap accurately to the bases. Under standard rules, a runner who overshoots the base will land off the basepaths and be automatically out.

So we might expect to see the runner bounding toward first base. Then one of the thirty or so far-left fielders would get the ball, relay it to the middle-left fielder and then the near-left fielder who would make the throw back to first. The throw would be inaccurate because it has to traverse a very large infield, and the first baseman would have to go chasing after it and pick it up from foul territory. He can't get back to first base quickly enough, but that's okay, the pitcher has bounded over from the mound and is waiting near first base to make the force play. Maybe the runner isn't there yet because one of his leaps was too long and to take another he has to jump high into the air and come down again.

It would work better than Quiddich, anyway.

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

Sun, 03 Mar 2024

Even without an alien invasion, February 22 on Talos I would have been a shitshow

One of my favorite videogames of the last few years, maybe my most favorite, is Prey. It was published in 2017, and developed by Arkane, the group that also created Dishonored. The publisher (Bethesda) sabotaged Prey by naming it after a beloved 2006 game also called Prey, with which it had no connection. Every fan of Prey (2006) who was hoping for a sequel was disappointed and savaged it. But it is a great, great game.

(I saw a video about the making of the 2017 Prey in which Raphael Colantonio talked about an earlier game of theirs, Dark Messiah of Might and Magic, which was not related to the Might and Magic series. But the publisher owned the Might and Magic IP, and thought the game would sell better if it was part of their established series. They stuck “Might and Magic” in the title, which disappointed all the Might and Magic fans, who savaged it. Then when Bethesda wanted to name Prey (2017) after their earlier game Prey (2006), Colantonio told them what had gone wrong the previous time they tried that strategy. His little shrug after he told that story broke my heart a little.)

This article contains a great many spoilers for the game, and also assumes you are familiar with the plot. It is unlikely to be of interest to anyone who is not familiar with Prey. You have been warned.

(If you're willing to check it out on my say-so, here's a link. I suggest you don't read the description, which contains spoilers. Just buy it and dive in.)

A recent question on Reddit's r/prey forum asked what would have

happened if the Typhon organisms had not broken out when they did.

The early plot of Prey is all there, but it is a little confusing,

because several things were happening at once. The short answer to

the question though, is that February 22, 2035 would have been the worst day

of Alex Yu's life even if his magnificent space station hadn't been

overrun by terrifying black aliens.

Morgan escapes the sim lab anyway

January had contingency plans for at least two situations. One was a Typhon escape, which we know all about.

But there was another plan for another situation. Morgan was having her memory erased before each round of testing. January explains that there was a procedure that was supposed to bring Morgan back up to speed after the tests were over. We know this procedure was followed for some time: Morgan's office has been used. Her assistant Jason Chang still hasn't gotten over his delight at working for such a hot boss. There are puzzled emails around asking why she never remembers her office combination. There's painful email from Mikhaila asking why Morgan is snubbing her. Clearly, at some point in the recent past, Morgan was still walking around the station in between tests, working and talking to people.

January's second contingency plan was in case Alex stopped bringing Morgan back up to speed after each round of tests, and just kept her in the simulation day after day — perhaps even more than once per day. (No wonder her eye is red!) And crucially, that plan was already in motion on February 22, the day the Typhon escaped.

The first thing that happens to the player in Prey is that Morgan fails all the tests. (“Is she…” “Yes, she's… hiding behind the chair.”) Why? We find out later Morgan was supposed to receive neuromods that would give her Typhon powers such as mimicry. They didn't. Marco Simmons says he installed exactly what Patricia brought down. There's email in the sim lab that asks Neuromod to check that something isn't wrong with the production process. But nothing is wrong with the production process. What really went wrong is that January had secretly replaced the neuromods with fakes, so that when they were removed from Morgan's brain, her memory wouldn't be affected. The next time Morgan woke up in her apartment and it was still March 15, she would realize what was happening.

It's hard to guess just what would have happened next, but I'm sure it would have been rather dramatic.

But that's not all

There are at least five other situations that would have blown up that same day. February 22 2035 on Talos I was always going to be an incredible shitshow.

Emmanuel Mendez

Because Frank Jones is a fuckup, Emmanuel Mendez has become aware that the escape pods don't work. He has decided to alert the crew by reprogramming the giant floating billboards to display “ESCAPE PODS ARE FAKE”. He completes this task on February 22 but dies without activating the program that will change the display.

Those billboards are visible from everywhere on the station, including the cafeteria.

Halden Graves

Halden Graves, head of the Neuromod Division, has just figured out that the neuromods, even the non-Typhon ones, are made with exotic material from the Typhon, and he completely loses his shit, to the point of chopping open his own head to get them out. That might attract some attention.

Josh Dalton

On February 22, Josh Dalton murdered Lane Carpenter with the BFG 9000 and then fled with it into the GUTS.

Alton Weber

Weber is on the Life Support security team. He has had a paranoid breakdown and stolen a shotgun. There's probably going to be a firefight outside the Life Support restrooms.

Mikhaila Ilyushin

Mikhaila is about to be arrested. Alex already suspected that something about her was fishy. Mikhaila has sent Divya Naaz to install snooping devices in the doors in Psychotronics, and Divya has been caught. Alex isn't going to wait any longer to stop Ilyushin.

Coming soon

These are starting to fall apart but the shit won't really hit the fan until sometime after February 22.

Annelise Gallegos and Quinten Purvis

Annelise Gallegos has been overcome by her conscience and is blowing the whistle on the experiments in Psychotronics and the murder of the “Volunteers”. On February 22, Alex has ordered Sarah Elazar to arrest her, as soon as her shift is over. The Typhon escape prevents that. What would have happened to Gallegos? I suspect she would would have died in an ⸢unfortunate accident⸣.

But it's too late for the Yus. Gallegos has already prepared her thumb drive with all the damning evidence, and Quinten Purvis has hidden with it in a cargo container. If the Typhon hadn't gotten loose that day, he would have been on his way to Earth with it.

[ Addendum 20240327: There's a hint that Sarah Elazar is on the trail, and I think I remember that she has sent someone to investigate the cargo hold, but it's not clear that they would have been able to stop Purvis. ]

Hunter Hale

Shuttles are supposed to take the Volunteers back to Earth when their service is complete. The Shuttle Bay flight control staff have recently noticed that the shuttles are not going straight back to Earth, but are stopping somewhere else just after leaving, and then proceeding to Earth on a slightly altered course.

What's really happening is that the shuttle pilot, Hunter Hale, makes a stop at the Psychotronics airlock and drops off some or all of the Volunteers so they can be turned into Neuromods.

Alex is paying Hale five times the normal salary to keep his mouth shut about this, but HR has noticed and is asking questions about it. Between the flight control staff and HR, the truth is going to come out.

[ Addendum 20240327: The security staff has brought the suspicious shuttle course to the attention of Sarah Elazar, who is going to investigate. ]

Sarah Elazar

Elazar suspects that the Yus are up to something dirty. She doesn't know what yet, but she's going to find out.

Disappearing neuromods

Everyone seems to be pilfering neuromods. Emmanuella Da Silva has some stashed in the drop ceiling of the Shuttle Bay locker room. Yuri Kimura has four under her desk, and Elias Black is blackmailing her. Lorenzo Calvino has some in both of his secret safes. Lily Morris has them hidden in the fire alarms in half a dozen places around the station. That dumbass Grant Lockwood has tried to walk back to Earth with his stolen neuromods.

I probably missed a few, they're all over.

(I said none of this would come to light until after February 22, but it won't be long before someone wonders what became of Lockwood. It's also possible Alex will find out about the Lily Morris conspiracy that day, from Eddie Voss. I almost feel sorry for Alex.)

[ Addendum 20240327: Elazar, as usual, is on the ball. She knows Lockwood is missing and has dispatched someone to find him. ]

Minor shit

Not giant disasters, but troublesome nevertheless.

Lorenzo Calvino

It won't be long before someone, probably Miyu Okabe, figures out that Lorenzo Calvino has a severe, progressive mental impairment.

Price Broadway

Broadway, the alcoholic in Waste Processing, is endangering everyone's lives by leaving empty vodka bottles in the eel tanks. His supervisor knows and has reported him to HR. She says HR will help, but I imagine they'll just fire him.

Maybe he'll end up on Hunter Hale's shuttle home.

Volunteers

What's up with the Volunteers in the dormitory in Neuromod Division? Some of them are stealing and selling supplies. Other are stealing dangerous equipment and weapons. What for?

Drama drama drama

Even without the Typhon, Prey could have been a great game!

You play Morgan, of course. The first fifteen minutes are the same, right up until Bellamy would have died.

When you wake up for the second time on March 15, you figure out what is happening, and confront the Sim Lab staff. You escape, go rogue, and make your way to the Arboretum to confront Alex. Meanwhile all sorts of stuff is going down. Alton Weber is on a rampage in Life Support. Josh Dalton is loose in the GUTS. You'll have to deal with him to get to the Arboretum. (What, did you think you were going to take the elevator?) Somewhere along the line you find out about Purvis in the cargo container and have to decide how to handle that. And then Mendez changes the billboards and there's a panic…

What else?

A lot is happening on Talos I. I probably left something out.

(The shortage of escape pods doesn't count. Someone would have noticed long ago that there aren't nearly enough. I think we have to assume that there are more escape pods than we see in the game. Perhaps Morgan's simulation omitted them.)

(And in my headcanon, that poor schmuck Kevin Hague never does find out his wife has cheated on him with the asshole football star.)

Let me know what I missed.

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

Wed, 17 May 2023

More notes about pain as a game mechanic

In a recent article on rarely-seen game mechanics, I suggested a variation on chess in which a player can force their opponent to retract their last move and play another, by cutting off one of their fingers. This provoked some interesting discussion. First some peripheral matters.

Bloody Knuckles

A couple of people reminded me of the game Bloody Knuckles, a straightforward pain tolerance game in which players take turns pumching one anothers' knuckles until someone gives in.

Slaps

Daniel Wagner also reminded me about the game of Slaps, also called “Red hands”. Wikipedia describes it this way:

One player extends their hands forward, roughly at arm's length, with the palms down. The other player's hands, also roughly at arm's length, are placed, palms up, under the first player's hands. The object of the game is for the second player to slap the back of the first player's hands before the first player can pull them away.

I enjoyed this game when I was younger but as far as I recall we did not play it as a pain tolerance game. For the second player to win it was enough to touch the first player's hands lightly. The first player's hands are held in the air, so there is a firm limit on how much damage the second player would be able to do.

PainStation

Rik Signes mentioned PainStation, a combination arcade game and conceptual art piece that can be found in the Computerspielemuseum (Computer Games Museum) in Berlin.

PainStation is a game of Pong whose interface incorporates a “pain execution unit” for each player that can deliver electric shocks, high heat, or strikes from a small wire whip. A player who removes their hand from the pain execution unit loses immediately.

Hot Dog Cold Dog

Jeb Boniakowski told me about a curious game they played on long winter trips in the car. First there is a “Cold Dog” round: the heat is turned off and the windows opened until one of the travelers gives up. Then there is a “Hot Dog” round: the windows are rolled up and the heat is turned on full blast until someone else gives up. Rounds continue to alternate until the car arrives at its destination, or everyone barfs, I suppose.

Finger-cutting in Chess

I wasn't sure this would be an actually useful option, but Hacker

News user fwlr persuaded

me that it would be. They have kindly given me permission to

republish their HN comment:

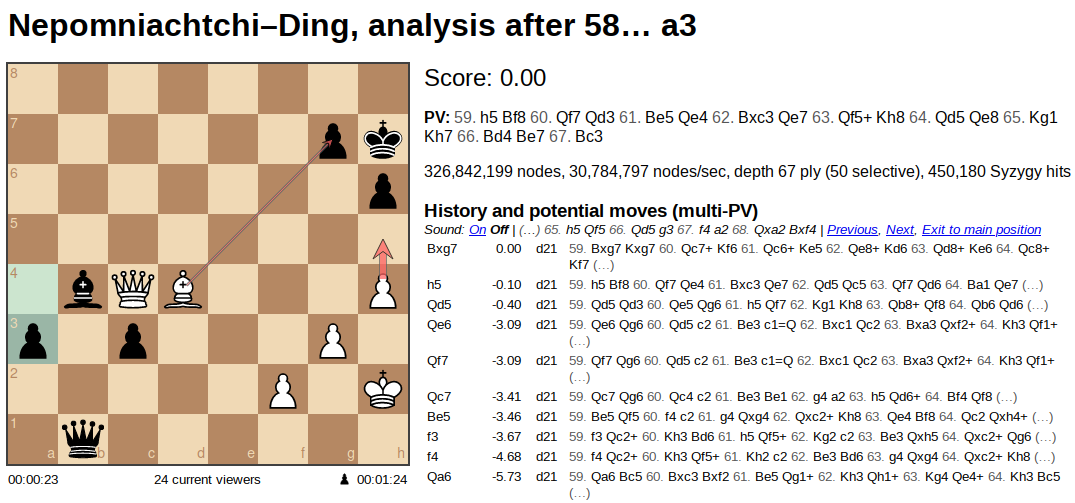

A lot of fantastic chess moments are about one player finding the only move that’s good, and high level chess is largely about creating these incredibly tense board positions where there are a lot of possible moves but only a few are safe. For example, Sesse’s analysis of the last [18th] championship game (can’t link to a specific move, use the bar chart or the Previous/Next hyperlinks to go to “analysis after 58… a3”).

This is 50+ moves into a fast paced game and according to supercomputer analysis it is a perfectly tied position. There are two possible moves that keep the game tied or close to tied [Bxg7, h4], and one more possible move [Qd5] that only gives up a very slight advantage (0.5 points is roughly “half a pawn’s value” and is close to the limit of what a human player can confidently detect, this moves gives four tenths of a pawn). Every other move gives up 3 points or more (roughly a full piece, like a bishop) — not always immediately, maybe five or ten moves down the track.

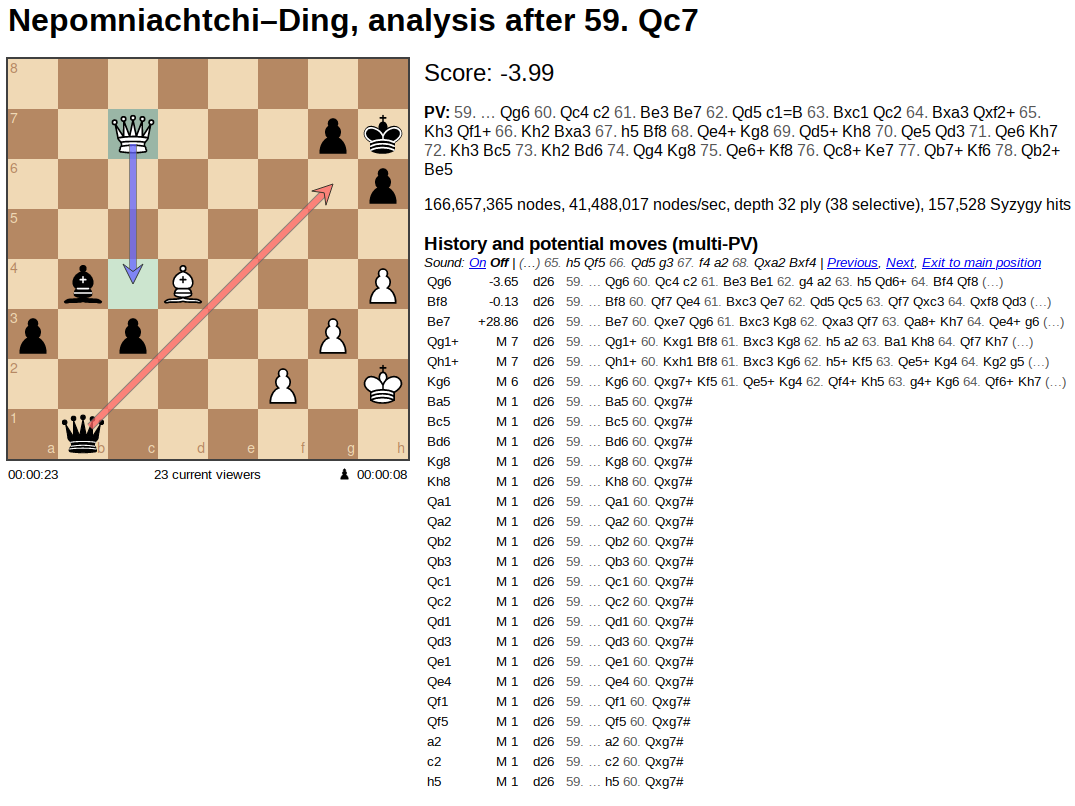

[Nepomniachtchi], playing white, makes one of those “bad” moves (Qc7), theoretically losing the equivalent of almost four whole pawns, a terrible blunder in the eyes of the all-seeing computer. But use the ‘Next’ link to look at the position in “analysis after 59 Qc7”.

There is one move, black Queen to g6, that takes advantage of the “blunder”. There is a second move, black Bishop to f8, that completely cedes the blunder and returns to a mostly-tied position. The third best possible move loses 32 points (going from -4 to +28…). Then there’s two dozen more possible moves, all of which literally lose the game on the spot. [‘M 6’ means that black can force mate in six moves; ‘M 1’ means that black can mate on the next move.]

So to recap: one move gets your opponent ahead, one move keeps him tied, and twenty-four moves lose him the entire game. Being able to cut off your finger to undo and prevent that one good move would change the entire dynamic from “a terrible blunder” to “a bold stroke of pure brilliance”.

In fact Ding did reply with 59…Qg6, the one move that took advantage of the blunder. He won the game, and with it, the world championship. Had Nepomniachtchi cut off a finger at that point, things might have gone differently. (Although his clock had only 23 seconds left, not much time for finger-chopping. Tough to say.)

It's unfortunate that the beautiful analysis page that fwlr links to

is so unsuitable. (For one thing, we can't link directly to the part

of interest; for another, the only way for the user to navigate there

is to click a teeny tiny red bar that is in a cluster of similar bars;

for another, it seems likely that the analysis will not remain at its

current URL. This is why I included screenshots, which are differently

unsatisfctory. If anyone knows of a link target without these

drawbacks, please let me know.

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

Fri, 27 Mar 2020Last week Pierre-Françoys Brousseau and I invented a nice chess variant that I've never seen before. The main idea is: two pieces can be on the same square. Sometimes when you try to make a drastic change to the rules, what you get fails completely. This one seemed to work okay. We played a game and it was fun.

Specfically, our rules say:

All pieces move and capture the same as in standard chess, except:

Up to two pieces may occupy the same square.

A piece may move into an occupied square, but not through it.

A piece moving into a square occupied by a piece of the opposite color has the option to capture it or to share the square.

Pieces of opposite colors sharing a square do not threaten one another.

A piece moving into a square occupied by two pieces of the opposite color may capture either, but not both.

Castling is permitted, but only under the same circumstances as standard chess. Pieces moved during castling must move to empty squares.

Miscellaneous notes

Pierre-Françoys says he wishes that more than two pieces could share a square. I think it could be confusing. (Also, with the chess set we had, more than two did not really fit within the physical confines of the squares.)

Similarly, I proposed the castling rule because I thought it would be less confusing. And I did not like the idea that you could castle on the first move of the game.

The role of pawns is very different than in standard chess. In this variant, you cannot stop a pawn from advancing by blocking it with another pawn.

Usually when you have the chance to capture an enemy piece that is alone on its square you will want to do that, rather than move your own piece into its square to share space. But it is not hard to imagine that in rare circumstances you might want to pick a nonviolent approach, perhaps to avoid a stalemate.

Some discussion of similar variants is on Chess Stack Exchange.

The name “Pauli Chess”, is inspired by the Pauli exclusion principle, which says that no more than two electrons can occupy the same atomic orbital.

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

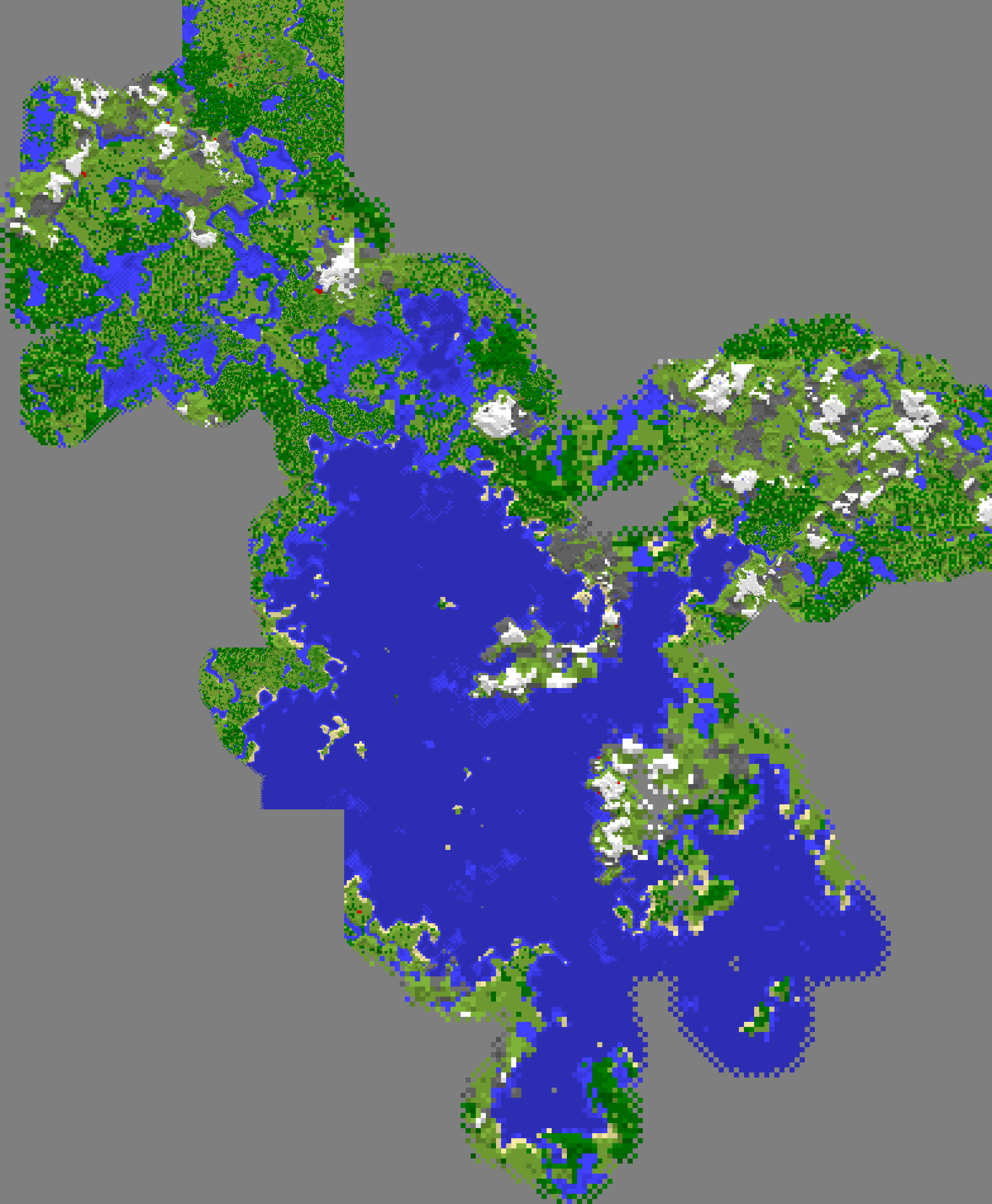

Wed, 10 Oct 2018Minecraft makes maps in-game, and until now I would hold up the map in the game, take a screenshot, print it out, and annotate the printout.

Now I can do better. I have a utility that takes multiple the map files direcly from the Minecraft data directory and joins them together into a single PNG image that I can then do whatever with. Here's a sample, made by automatically processing the 124(!) maps that exist in my current Minecraft world.

Notice how different part of the result are at different resolutions. That is because Minecraft maps are in five different resolutions, from !!2^{14}!! to !!2^{22}!! square meters in area, and these have been stitched together properly. My current base of operations is a little comma-shaped thingy about halfway down in the middle of the ocean, and on my largest ocean map it is completely invisible. But here it has been interpolated into the correct tiny scrap of that big blue map.

Bonus: If your in-game map is lost or destroyed, the data file still hangs around, and you can recover the map from it.

Source code is on Github. It needs some work:

- You have to manually decompress the map files

- It doesn't show banners or other markers

- I got bored typing in the color table and didn't finish

- Invoking it is kind of heinous

./dumpmap $(./sortbyscale map_*) | pnmtopng > result.png

Patches welcome!

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

Mon, 12 Feb 2018

Philadelphia sports fans behaving badly

Philadelphia sports fans have a bad reputation. For example, we are famous for booing Santa Claus and hitting him with snowballs. I wasn't around for that; it happened in 1968. When the Santa died in 2015, he got an obituary in the Phildelphia Inquirer:

Frank Olivo, the Santa Claus who got pelted with snowballs at the Eagles game that winter day in 1968, died Thursday, April 30…

The most famous story of this type is about Ed Rendell (after he was Philadelphia District Attorney, but before he was Mayor) betting a Eagles fan that they could not throw snowballs all the way from their upper-deck seat onto the field. This was originally reported in 1989 by Steve Lopez in the Inquirer.

(Lopez's story is a blast. He called up Rendell, who denied the claim, and referred Lopez to a friend who had been there with him. Lopez left a message for the friend. Then Rendell called back to confess. Later Rendell's friend called back to deny the story. Lopez wrote:

Was former D.A. Ed Rendell's worst mistake to (A) bet a drunken hooligan he couldn't reach the field, (B) lie about it, (C) confess, or (D) take his friend down with him?

My vote is C. Too honest. Why do you think he can't win an election?

A few years later Rendell was elected Mayor of Philadelphia, and later, Governor of Pennsylvania. Anyway, I digress.)

I don't attend football games, and baseball games are not held in snowy weather, so we have to find other things to throw on the field. I am too young to remember Bat Day, where each attending ticket-holder was presented with a miniature souvenir baseball bat; that was eliminated long ago because too many bats were thrown at the visiting players. (I do remember when those bats stopped being sold at the concession stands, for the same reason.) Over the years, all the larger and harder premiums were eliminated, one by one, but we are an adaptable people and once, to protest a bad call by the umpire, we delayed the game by wadding up our free promotional sport socks and throwing them onto the field. That was the end of Sock Day.

On one memorable occasion, two very fat gentlemen down by the third-base line ran out of patience during an excessively long rain delay and climbed over the fence, ran out and belly-flopped onto the infield, sliding on the wet tarpaulin all the way to the first-base side. Confronted there by security, they evaded capture by turning around and sliding back. These heroes were eventually run down, but only after livening up what had been a very trying evening.

The main point of this note is to shore up a less well-known story of this type. I have seen it reported that Phillies fans once booed Miss Pennsylvania, and I have also seen people suggest that this never really happened. On my honor, it did happen. We not only booed Miss Pennsylvania, we booed her for singing the national anthem. I was at that game, in 1993. The Star-Spangled Banner has a lot of problems that the singer must solve one way or another, and there are a lot of ways to interpret it. But it has a melody, and the singer's interpretation is not permitted to stray so far from the standard that they are singing a different song that happens to have the same words. I booed too, and I'm not ashamed to admit it.

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

Sat, 23 Apr 2016

Steph Curry: fluke or breakthrough?

[ Disclaimer: I know very little about basketball. I think there's a good chance this article contains at least one basketball-related howler, but I'm too ignorant to know where it is. ]

Randy Olson recently tweeted a link to a New York Times article about Steph Curry's new 3-point record. Here is Olson’s snapshot of a portion of the Times’ clever and attractive interactive chart:

(Skip this paragraph if you know anything about basketball. The object of the sport is to throw a ball through a “basket” suspended ten feet (3 meters) above the court. Normally a player's team is awarded two points for doing this. But if the player is sufficiently far from the basket—the distance varies but is around 23 feet (7 meters)—three points are awarded instead. Carry on!)

The chart demonstrates that Curry this year has shattered the single-season record for three-point field goals. The previous record, set last year, is 286, also by Curry; the new record is 406. A comment by the authors of the chart says

The record is an outlier that defies most comparisons, but here is one: It is the equivalent of hitting 103 home runs in a Major League Baseball season.

(The current single-season home run record is 73, and !!\frac{406}{286}·73 \approx 103!!.)

I found this remark striking, because I don't think the record is an outlier that defies most comparisons. In fact, it doesn't even defy the comparison they make, to the baseball single-season home run record.

In 1919, the record for home runs in a single season was 29, hit by Babe Ruth. The 1920 record, also by Ruth, was 54. To make the same comparison as the authors of the Times article, that is the equivalent of hitting !!\frac{54}{29}·73 \approx 136!! home runs in a Major League Baseball season.

No, far from being an outlier that defies most comparisons, I think what we're seeing here is something that has happened over and over in sport, a fundamental shift in the way the game is played; in short, a breakthrough. In baseball, Ruth's 1920 season was the end of what is now known as the dead-ball era. The end of the dead-ball era was the caused by the confluence of several trends (shrinking ballparks), rule changes (the spitball), and one-off events (Ray Chapman, the Black Sox). But an important cause was simply that Ruth realized that he could play the game in a better way by hitting a crapload of home runs.

The new record was the end of a sudden and sharp upward trend. Prior to Ruth's 29 home runs in 1919, the record had been 27, a weird fluke set way back in 1887 when the rules were drastically different. Typical single-season home run records in the intervening years were in the 11 to 16 range; the record exceeded 20 in only four of the intervening 25 years.

Ruth's innovation was promptly imitated. In 1920, the #2 hitter hit 19 home runs and the #10 hitter hit 11, typical numbers for the nineteen-teens. By 1929, the #10 hitter hit 31 home runs, which would have been record-setting in 1919. It was a different game.

For another example of a breakthrough, let's consider competitive hot dog eating. Between 1980 and 1990, champion hot-dog eaters consumed between 9 and 16 hot dogs in 10 minutes. In 1991 the time was extended to 12 minutes and Frank Dellarosa set a new record, 21½ hot dogs, which was not too far out of line with previous records, and which was repeatedly approached in the following decade: through 1999 five different champions ate between 19 and 24½ hot dogs in 12 minutes, in every year except 1993.

But in 2000 Takeru Kobayashi (小林 尊) changed the sport forever, eating an unbelievably disgusting 50 hot dogs in 12 minutes. (50. Not a misprint. Fifty. Roman numeral Ⅼ.) To make the Times’ comparison again, that is the equivalent of hitting !!\frac{50}{24\frac12}·73 \approx 149!! home runs in a Major League Baseball season.

At that point it was a different game. Did the record represent a fundamental shift in hot dog gobbling technique? Yes. Kobayashi won all of the next five contests, eating between 44½ and 53¾ each time. By 2005 the second- and third-place finishers were eating 35 or more hot dogs each; had they done this in 1995 they would have demolished the old records. A new generation of champions emerged, following Kobayashi's lead. The current record is 69 hot dogs in 10 minutes. The record-setters of the 1990s would not even be in contention in a modern hot dog eating contest.

It is instructive to compare these breakthroughs with a different sort of astonishing sports record, the bizarre fluke. In 1967, the world record distance for the long jump was 8.35 meters. In 1968, Bob Beamon shattered this record, jumping 8.90 meters. To put this in perspective, consider that in one jump, Beamon advanced the record by 55 cm, the same amount that it had advanced (in 13 stages) between 1925 and 1967.

Progression of the world long jump record

The cliff at 1968 is Bob Beamon

Did Beamon's new record represent a fundamental shift in long jump technique? No: Beamon never again jumped more than 8.22m. Did other jumpers promptly imitate it? No, Beamon's record was approached only a few times in the following quarter-century, and surpassed only once. Beamon had the benefit of high altitude, a tail wind, and fabulous luck.

Another bizarre fluke is Joe DiMaggio's hitting streak: in the 1941 baseball season, DiMaggio achieved hits in 56 consecutive games. For extensive discussion of just how bizarre this is, see The Streak of Streaks by Stephen J. Gould. (“DiMaggio’s streak is the most extraordinary thing that ever happened in American sports.”) Did DiMaggio’s hitting streak represent a fundamental shift in the way the game of baseball was played, toward high-average hitting? Did other players promptly imitate it? No. DiMaggio's streak has never been seriously challenged, and has been approached only a few times. (The modern runner-up is Pete Rose, who hit in 44 consecutive games in 1978.) DiMaggio also had the benefit of fabulous luck.

Is Curry’s new record a fluke or a breakthrough?

I think what we're seeing in basketball is a breakthrough, a shift in the way the game is played analogous to the arrival of baseball’s home run era in the 1920s. Unless the league tinkers with the rules to prevent it, we might expect the next generation of players to regularly lead the league with 300 or 400 three-point shots in a season. Here's why I think so.

Curry's record wasn't unprecedented. He's been setting three-point records for years. (Compare Ruth’s 1920 home run record, foreshadowed in 1919.) He's continuing a trend that he began years ago.

Curry’s record, unlike DiMaggio’s streak, does not appear to depend on fabulous luck. His 402 field goals this year are on 886 attempts, a 45.4% success rate. This is in line with his success rate every year since 2009; last year he had a 44.3% success rate. Curry didn't get lucky this year; he had 40% more field goals because he made almost 40% more attempts. There seems to be no reason to think he couldn't make the same number of attempts next year with equal success, if he wants to.

Does he want to? Probably. Curry’s new three-point strategy seems to be extremely effective. In his previous three seasons he scored 1786, 1873, and 1900 points; this season, he scored 2375, an increase of 475, three-quarters of which is due to his three-point field goals. So we can suppose that he will continue to attempt a large number of three-point shots.

Is this something unique to Curry or is it something that other players might learn to emulate? Curry’s three-point field goal rate is high, but not exceptionally so. He's not the most accurate of all three-point shooters; he holds the 62nd–64th-highest season percentages for three-point success rate. There are at least a few other players in the league who must have seen what Curry did and thought “I could do that”. (Kyle Korver maybe? I'm on very shaky ground; I don't even know how old he is.) Some of those players are going to give it a try, as are some we haven’t seen yet, and there seems to be no reason why some shouldn't succeed.

A number of things could sabotage this analysis. For example, the league might take steps to reduce the number of three-point field goals, specifically in response to Curry’s new record, say by moving the three-point line farther from the basket. But if nothing like that happens, I think it's likely that we'll see basketball enter a new era of higher offense with more three-point shots, and that future sport historians will look back on this season as a watershed.

[ Addendum 20160425: As I feared, my Korver suggestion was ridiculous. Thanks to the folks who explained why. Reason #1: He is 35 years old. ]

[ Addendum 20210627: Blog article about the slowness with which the league adapted to the three-point rule. ]

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

Wed, 24 Jan 2007

Length of baseball games

In an earlier

article, I asserted that the average length of a baseball game was

very close to 9 innings. This is a good rule of thumb, but it is also

something of a coincidence, and might not be true in every year.

The canonical game, of course, lasts 9 innings. However, if the score is tied at the end of 9 innings, the game can, and often does, run longer, because the game is extended to the end of the first complete inning in which one team is ahead. So some games run longer than 9 innings: games of 10 and 11 innings are quite common, and the major-league record is 25.

Counterbalancing this effect, however, are two factors. Most important is that when the home team is ahead after the first half of the ninth inning, the second half is not played, since it would be a waste of time. So nearly half of all games are only 8 1/2 innings long. This depresses the average considerably. Together with the games that are stopped early on account of rain or other environmental conditions, the contribution from the extra-inning tie games is almost exactly cancelled out, and the average ends up close to 9.

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

Thu, 16 Nov 2006

Etch-a-Sketch blue-skying, corrected

In my last article I

discussed a scheme for improving the Etch-a-Sketch which contained a serious

mechanical error. I was discussing attaching gears to the two knobs

of the Etch-a-Sketch to force them to turn at the exact same rate. Supposing

that the distance between the knobs is 1 unit, I said, then we can

gear the two knobs together by attaching a gear of radius 1/2 to each

knob; the two gears will mesh, and the knobs will then turn at the same

rate, in opposite directions. This was fine.

Then I went astray, and suggested adding an axle peg midway between the two knobs, and putting gears of radius 1/3 on the peg and on the two knobs. This won't work.

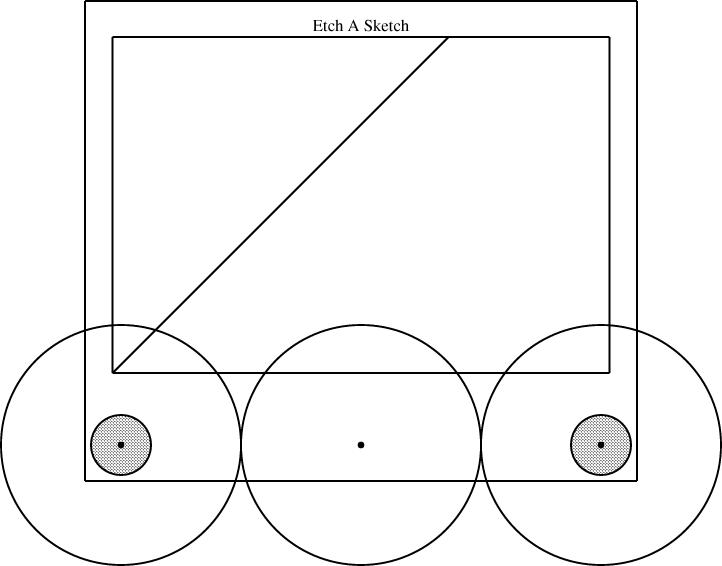

The one person who wrote to me to ask about the problem is a very bright person, but been seriously confused about how I was planning to set up the gears, so I evidently I didn't explain it very well. It needed a picture. So this time I'm going to try to get it right, with pictures. Here is an Etch-a-Sketch:

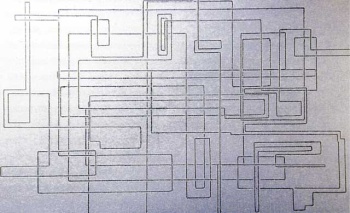

Here are some gears, which happen to have radii 1/3, 1/4, and 1/6:

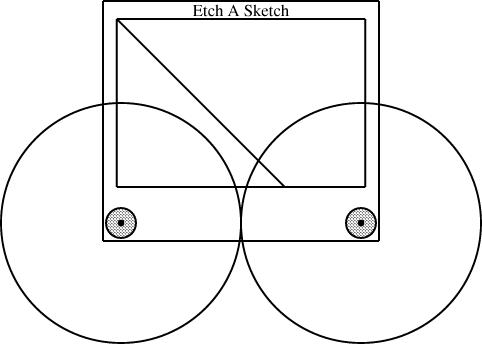

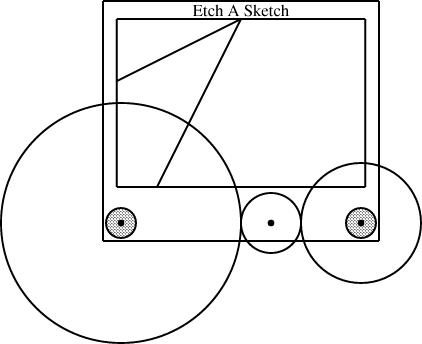

Here's a picture of an Etch-a-Sketch with a radius-1/2 gear mounted on each knob:

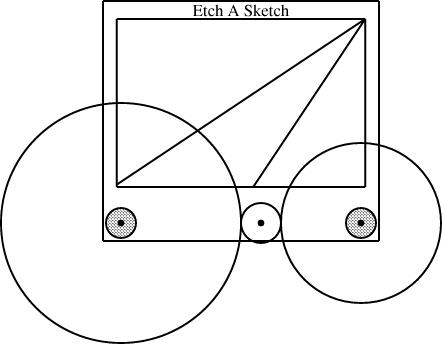

Here the knobs have been fitted with different-sized gears, one with radius 1/3 and the other with radius 2/3:

Then I suggested that you could drill a little hole in between the two knobs, and use it to mount a third axle and a third gear. If all three gears are the same size, the two knobs are forced to turn at the same rate, this time in the same direction, and you get a line with slope 1, from southeast to northwest:

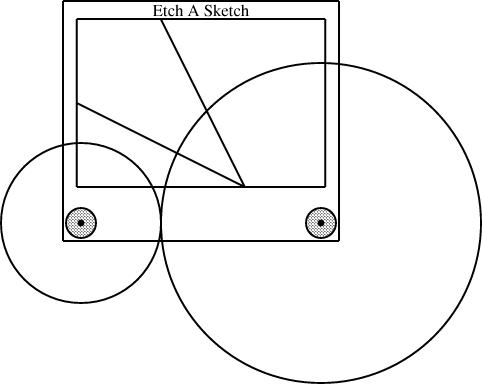

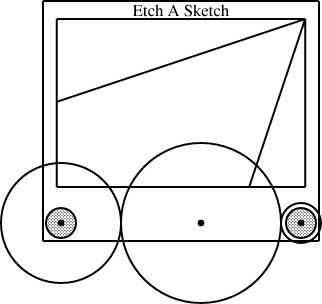

This wrecks the rest of the details of my other article. Since we were already including gears of size 1/2 and 1/3, I reasoned, we can throw in a gear of size 1/6 and get some new behaviors from the 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/6 combination. The corresponding combination for 1/2 and 1/4 is 1/8:

So what next? The calculations are a bit less obvious than they were back in the happy days when I thought that installing two gears of size p and q left space for one of size 1-(p+q). It's tempting to consider a radius-1/3 gear next, since it's the simplest size I haven't yet installed. But to mount it on the knobs along with a size-1/2 gear, we need to include a size-1/12 gear to go in between:

Once we have the size-1/12 gear, we can mount it with the size-1/4 and size-1/3 that we already had:

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link

Sun, 12 Nov 2006

Etch-a-Sketch

I've always felt that the Etch-a-Sketch is a superb example of a toy

that doesn't do as much as it could.

An Etch-a-Sketch is a drawing toy invented in 1959 by Arthur Granjean and marketed by the Ohio Art company since shortly afterward. It looks superficially like a flat-screen television with two knobs.

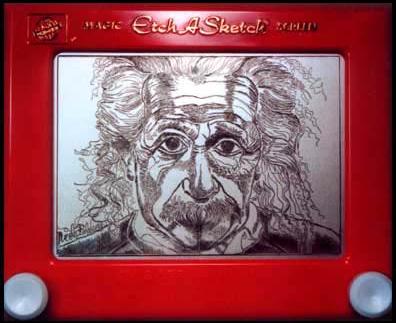

It is very easy to draw horizontal and vertical lines, but very difficult to draw diagonal lines. (Wikipedia says "Creating a straight diagonal line or smoothly curved line with an Etch A Sketch is notoriously difficult and a true test of coordination.") So although extremely complex drawings can be made with an Etch-a-Sketch:

(Etch-a-Sketch drawing of

Albert Einstein by Nicole

Falzone)

But it needn't be so. The most frustrating thing about the Etch-a-Sketch, I think, is that its potential has not yet begun to be unlocked.

Consider a forty-five degree line. To draw such a line, one must turn both the horizontal and the vertical knobs at the same time, at exactly the same rate. Suppose, for concreteness, that we're drawing a line from the upper left to the lower right. If you turn the horizontal knob a little too quickly, the diagonal line will bend rightward; if you turn it a little too slowly the diagonal line will bend downward. So in contrast to the mathematically exact vertical and horizontal lines that are easy to draw, it's next to impossible to draw a diagonal line that doesn't wiggle. And when you screw up, you can't fix the mistake without erasing the whole thing and starting over.

But the solution is obvious: If you can link the two knobs somehow, so that they can only turn simultaneously, you can easily draw a diagonal line. As a child, I experimented with rubber bands, trying to get one knob to drive the other. This wasn't successful. Clearly, a better solution is to use gears.

There are plenty of examples of toys that have good-quality cast-plastic gears. (Spirograph is one such.) The knobs on the Etch-a-Sketch could be geared together. If the gears are the same size, the knobs will rotate at the same rate, and the result will be a perfect 45° line.

If you gear the two knobs together directly, they will rotate in opposite directions, so that you can only draw lines with slope -1 (northwest to southeast), not with slope 1 (northeast to southwest). To fix this problem, we need to introduce more gears. There can be an axle peg sticking up from the case of the Etch-a-Sketch, in between the two knobs. Mounting three equal-sized gears on the two knobs and the axle peg gears will force the knobs to rotate in the same direction, at the same rate.

[ The remainder of this article contains a number of very dumb arithmetic errors. For example, you cannot fit three gears of size 1/3 on the knobs and pegs; you need to use three gears of size 1/4 instead. I will correct this on Monday, and provide an illustration to make it clearer what I mean. —MJD ]

[ Addendum 20061116: I have posted the correction, with illustrations. ]

Let's say that the distance between the centers of the two knobs is 1. We can get a line of slope -1 by mounting two gears, each with radius 1/2, on the two knobs; we can get a line of slope +1 by mounting three gears, each with radius 1/3, on the two knobs and on the axle peg. If we want to do both, we had better make the axle peg removable, or else it will interfere with the size-1/2 gears. This is no problem. It can mount into a socket on the front of the Etch-a-Sketch, and be pulled out when not needed.

But why have only one socket? We're including five gears already (two of size 1/2 and three of size 1/3) so we may as well put them to some more use. Throw in a size 1/6 gear, and add another socket for the axle peg, this time 1/3 of the way between the two knobs. Now you can mount a size 1/2 gear on the left knob, a size 1/6 gear on the axle peg, and a size 1/3 gear on the right knob. If the left knob turns at rate r, the middle gear turns at rate -3r and the right knob turns at rate 3r/2. This produces a line with slope 3/2, which is about a 56-degree angle.

Or put in another socket for the axle peg, 1/6 of the way between the knobs, and then mount size 1/2, size 1/3, and size 1/6 gears, in that order. The knobs are now producing a line with slope 3, a 72-degree angle. If you want a line with slope 1/3 (18°) instead, just reverse the order of the gears. (That is, exchange the large and the small ones.)

At this point adding a few more gears expands the repertoire significantly. Add a radius-2/3 gear and another radius-1/6 gear and you can mount [2/3, 1/3] to get lines with slope -1/2, [1/3, 2/3] to get slope -2, [2/3, 1/6, 1/6] to get slope 4, [1/6, 1/6, /23] to get slope 1/4.

Clearly, you can carry this onwards, limited only by the space for the axle holes and the expense of adding in more gears. Spirograph used to deliver fifteen or twenty plastic gears for a reasonable price, so it's clearly not implausible that Ohio Art could have done something like this.

Sometimes I even dare to think that they might have provided cams or elliptical gears. Properly designed cams could gear together the knobs to produce mathematically exact curved lines, squiggles, maybe even circles.

But no, as far as I can tell, it's never been done. Why not?

[Other articles in category /games] permanent link