Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | J |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

| Cathedrals of various sorts |

| “Llaves” and other vanishing consonants |

| Quick Spanish etymology question |

| The disembodied heads of Oz |

| What's long and hard? |

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Sat, 28 May 2022

“Llaves” and other vanishing consonants

Lately I asked:

Where did the ‘c’ go in llave (“key”)? It's from Latin clavīs…

Several readers wrote in with additional examples, and I spent a little while scouring Wiktionary for more. I don't claim that this list is at all complete; I got bored partway through the Wiktionary search results.

| Spanish | English | Latin antecedent |

|---|---|---|

| llagar | to wound | plāgāre |

| llama | flame | flamma |

| llamar | to summon, to call | clāmāre |

| llano | flat, level | plānus |

| llantén | plaintain | plantāgō |

| llave | key | clavis |

| llegar | to arrive, to get, to be sufficient | plicāre |

| lleno | full | plēnus |

| llevar | to take | levāre |

| llorar | to cry out, to weep | plōrāre |

| llover | to rain | pluere |

I had asked:

Is this the only Latin word that changed ‘cl’ → ‘ll’ as it turned into Spanish, or is there a whole family of them?

and the answer is no, not exactly. It appears that llave and llamar are the only two common examples. But there are many examples of the more general phenomenon that

(consonant) + ‘l’ → ‘ll’

including quite a few examples where the consonant is a ‘p’.

Spanish-related notes

Eric Roode directed me to this discussion of “Latin CL to Spanish LL” on the WordReference.com language forums. It also contains discussion of analogous transformations in Italian. For example, instead of plānus → llano, Italian has → piano.

Alex Corcoles advises me that Fundéu often discusses this sort of issue on the Fundéu web site, and also responds to this sort of question on their Twitter account. Fundéu is the Foundation of Emerging Spanish, a collaboration with the Royal Spanish Academy that controls the official Spanish language standard.

Several readers pointed out that although llave is the key that opens your door, the word for musical keys and for encryption keys is still clave. There is also a musical instrument called the claves, and an associated technical term for the rhythmic role they play. Clavícula (‘clavicle’) has also kept its ‘c’.

The connection between plicāre and llegar is not at all clear to me. Plicāre means “to fold”; English cognates include ‘complicated’, ‘complex’, ‘duplicate’, ‘two-ply’, and, farther back, ‘plait’. What this has to do with llegar (‘to arrive’) I do not understand. Wiktionary has a long explanation that I did not find convincing.

The levāre → llevar example is a little weird. Wiktionary says "The shift of an initial 'l' to 'll' is not normal".

Llaves also appears to be the Spanish name for the curly brace characters

{and}. (The square brackets are corchetes.)

Not related to Spanish

The llover example is a favorite of the Universe of Discourse, because Latin pluere is the source of the English word plover.

French parler (‘to talk’) and its English descendants ‘parley’ and ‘parlor’ are from Latin parabola.

Latin plōrāre (‘to cry out’) is obviously the source of English ‘implore’ and ‘deplore’. But less obviously, it is the source of ‘explore’. The original meaning of ‘explore’ was to walk around a hunting ground, yelling to flush out the hidden game.

English ‘autoclave’ is also derived from clavis, but I do not know why.

Wiktionary's advanced search has options to order results by “relevance” and last-edited date, but not alphabetically!

Thanks

- Thanks to readers Michael Lugo, Matt Hellige, Leonardo Herrera, Leah Neukirchen, Eric Roode, Brent Yorgey, and Alex Corcoles for hints clues, and references.

[ Addendum: Andrew Rodland informs me that an autoclave is so-called because the steam pressure inside it forces the door lock closed, so that you can't scald yourself when you open it. ]

[ Addendum 20230319: llevar, to rise, is akin to the English place name Levant which refers to the region around Syria, Israel, Lebanon, and Palestine: the “East”. (The Catalán word llevant simply means “east”.) The connection here is that the east is where the sun (and everything else in the sky) rises. We can see the same connection in the way the word “orient”, which also means an eastern region, is from Latin orior, “to rise”. ]

[Other articles in category /lang/etym] permanent link

Thu, 26 May 2022

Quick Spanish etymology question

Where did the ‘c’ go in llave (“key”)? It's from Latin clavīs, like in “clavicle”, “clavichord”, “clavier” and “clef”.

Is this the only Latin word that changed ‘cl’ → ‘ll’ as it turned into Spanish, or is there a whole family of them?

[ Addendum 20220528: There are more examples. ]

[Other articles in category /lang/etym] permanent link

Sat, 21 May 2022Sometime in the previous millennium, my grandfather told me this joke:

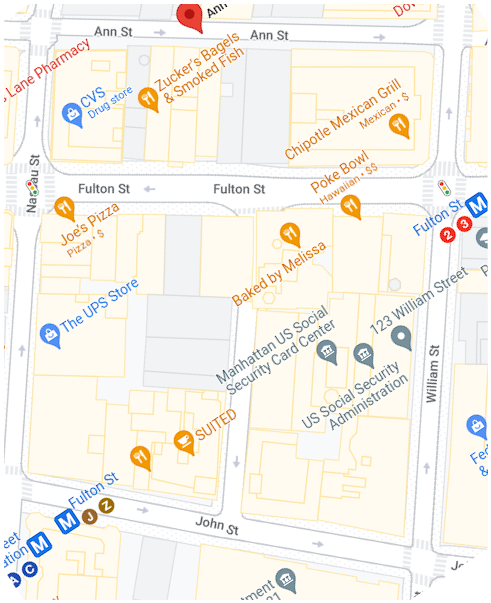

Why is Fulton Street the hottest street in New York?

Because it lies between John and Ann.

I suppose this might have been considered racy back when he heard it from his own grandfather. If you didn't get it, don't worry, it wasn't actually funny.

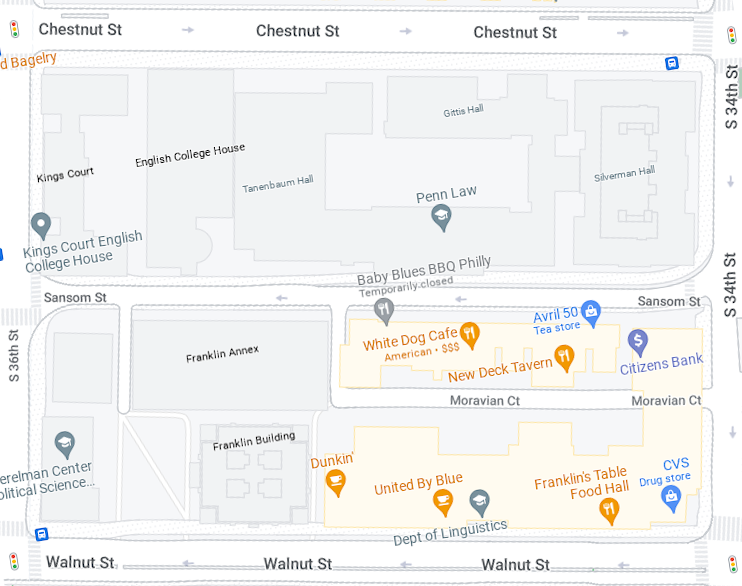

Today I learned the Philadelphia version of the joke, which is a little better:

What's long and black and lies between two nuts?

Sansom Street.

I think it that the bogus racial flavor improves it (it looks like it might turn out to be racist, and then doesn't). Some people may be more sensitive; to avoid making them uncomfortable, one can replace the non-racism with additional non-obscenity and ask instead “what's long and stiff and lies between two nuts?”.

There was a “what's long and stiff” joke I heard when I was a kid:

What's long and hard and full of semen?

A submarine.

Eh, okay. My opinion of puns is that they can be excellent, when they are served hot and fresh, but they rapidly become stale and heavy, they are rarely good the next day, and the prepackaged kind is never any good at all.

The antecedents of the “what's long and stiff” joke go back hundreds of years. The Exeter Book, dating to c. 950 CE, contains among other things ninety riddles, including this one I really like:

A curious thing hangs by a man's thigh,

under the lap of its lord. In its front it is pierced,

it is stiff and hard, it has a good position.

When the man lifts his own garment

above his knee, he intends to greet

with the head of his hanging object that familiar hole

which is the same length, and which he has often filled before.

(The implied question is “what is it?”.)

The answer is of course a key. Wikipedia has the original Old English if you want to compare.

Finally, it is off-topic but I do not want to leave the subject of the Exeter Book riddles without mentioning riddle #86. It goes like this:

Wiht cwom gongan

þær weras sæton

monige on mæðle,

mode snottre;

hæfde an eage

ond earan twa,

ond II fet,

XII hund heafda,

hrycg ond wombe

ond honda twa,

earmas ond eaxle,

anne sweoran

ond sidan twa.

Saga hwæt ic hatte.

I will adapt this very freely as:

What creature has two legs and two feet, two arms and two hands, a back and a belly, two ears and twelve hundred heads, but only one eye?

The answer is a one-eyed garlic vendor.

[Other articles in category /humor] permanent link

Sat, 14 May 2022A while back I wrote a shitpost about octahedral cathedrals and in reply Daniel Wagner sent me this shitpost of a cat-hedron:

But that got me thinking: the ‘hedr-’ in “octahedron” (and other -hedrons) is actually the Greek word ἕδρα (/hédra/) for “seat”, and an octahedron is a solid with eight “seats”. The ἕδρα (/hédra/) is akin to Latin sedēs (like in “sedentary”, or “sedate”) by the same process that turned Greek ἡμι- (/hémi/, like in “hemisphere”) into Latin semi- (like in “semicircle”) and Greek ἕξ (/héx/, like in “hexagon”) into Latin sex (like in “sextet”).

So a cat-hedron should be a seat for cats. Such seats do of course exist:

But I couldn't stop there because the ‘hedr-’ in “cathedral” is the same word as the one in “octahedron”. A “cathedral” is literally a bishop's throne, and cathedral churches are named metonymically for the literal throne they contain or the metaphorical one represent. A cathedral is where a bishop has his “seat” of power.

So a true cathedral should look like this:

[Other articles in category /lang/etym] permanent link

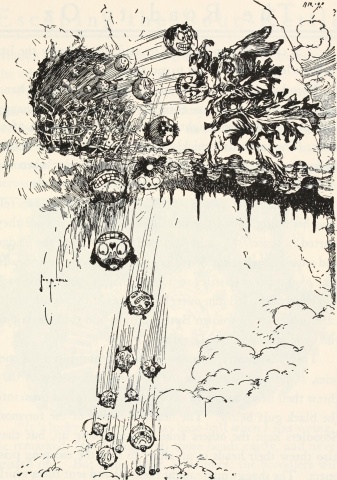

Tue, 03 May 2022The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

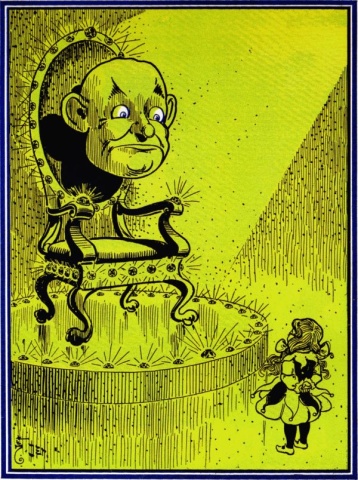

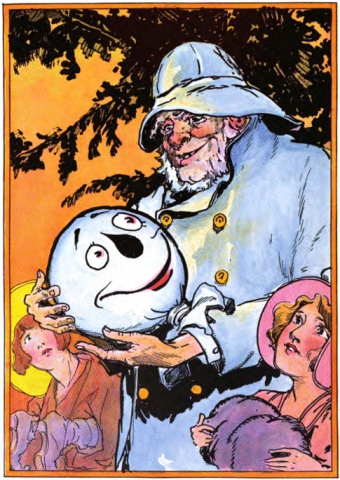

Certainly the best-known and most memorable of the disembodied heads of Oz is the one that the Wizard himself uses when he first appears to Dorothy:

In the center of the chair was an enormous Head, without a body to support it or any arms or legs whatever. There was no hair upon this head, but it had eyes and a nose and mouth, and was much bigger than the head of the biggest giant.

As Dorothy gazed upon this in wonder and fear, the eyes turned slowly and looked at her sharply and steadily. Then the mouth moved, and Dorothy heard a voice say:

“I am Oz, the Great and Terrible. Who are you, and why do you seek me?”

Those Denslow illustrations are weird. I wonder if the series would have lasted as long as it did, if Denslow hadn't been replaced by John R. Neill in the sequel.

This head, we learn later, is only a trick:

He pointed to one corner, in which lay the Great Head, made out of many thicknesses of paper, and with a carefully painted face.

"This I hung from the ceiling by a wire," said Oz; "I stood behind the screen and pulled a thread, to make the eyes move and the mouth open."

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz has not one but two earlier disembodied heads, not fakes but violent decaptitations. The first occurs offscreen, in the Tin Woodman's telling of how he came to be made of tin; I will discuss this later. The next to die is an unnamed wildcat that was chasing the queen of the field mice:

So the Woodman raised his axe, and as the Wildcat ran by he gave it a quick blow that cut the beast’s head clean off from its body, and it rolled over at his feet in two pieces.

Later, the Wicked Witch of the West sends a pack of forty wolves to kill the four travelers, but the Woodman kills them all, decapitating at least one:

As the leader of the wolves came on the Tin Woodman swung his arm and chopped the wolf's head from its body, so that it immediately died. As soon as he could raise his axe another wolf came up, and he also fell under the sharp edge of the Tin Woodman's weapon.

After the Witch is defeated, the travelers return to Oz, to demand their payment. The Scarecrow wants brains:

“Oh, yes; sit down in that chair, please,” replied Oz. “You must excuse me for taking your head off, but I shall have to do it in order to put your brains in their proper place.” … So the Wizard unfastened his head and emptied out the straw.

On the way to the palace of Glinda, the travelers pass through a forest whose inhabitants have been terrorized by a giant spider monster:

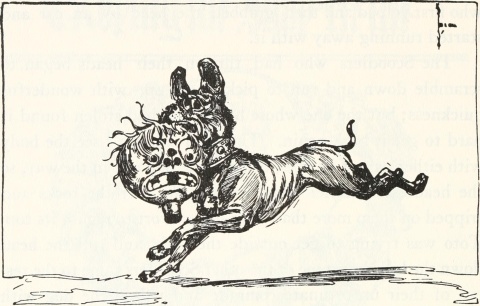

Its legs were quite as long as the tiger had said, and its body covered with coarse black hair. It had a great mouth, with a row of sharp teeth a foot long; but its head was joined to the pudgy body by a neck as slender as a wasp's waist. This gave the Lion a hint of the best way to attack the creature… with one blow of his heavy paw, all armed with sharp claws, he knocked the spider's head from its body.

That's the last decapitation in that book. Oh wait, not quite. They must first pass over the hill of the Hammer-Heads:

He was quite short and stout and had a big head, which was flat at the top and supported by a thick neck full of wrinkles. But he had no arms at all, and, seeing this, the Scarecrow did not fear that so helpless a creature could prevent them from climbing the hill.

It's not as easy as it looks:

As quick as lightning the man's head shot forward and his neck stretched out until the top of the head, where it was flat, struck the Scarecrow in the middle and sent him tumbling, over and over, down the hill. Almost as quickly as it came the head went back to the body, …

So not actually a disembodied head. The Hammer-Heads get only a Participation trophy.

Well! That gets us to the end of the first book. There are 13 more.

The Marvelous Land of Oz

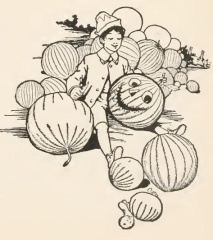

One of the principal characters in this book is Jack Pumpkinhead, who is a magically animated wooden golem, with a carved pumpkin for a head.

The head is not attached too well. Even before Jack is brought to life, his maker observes that the head is not firmly attached:

Tip also noticed that Jack's pumpkin head had twisted around until it faced his back; but this was easily remedied.

This is a recurring problem. Later on, the Sawhorse complains:

"Even your head won't stay straight, and you never can tell whether you are looking backwards or forwards!"

The imperfect attachement is inconvenient when Jack needs to flee:

Jack had ridden at this mad rate once before, so he devoted every effort to holding, with both hands, his pumpkin head upon its stick…

Unfortunately, he is not successful. The Sawhorse charges into a river:

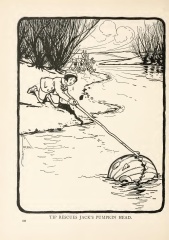

The wooden body, with its gorgeous clothing, still sat upright upon the horse's back; but the pumpkin head was gone, and only the sharpened stick that served for a neck was visible.… Far out upon the waters [Tip] sighted the golden hue of the pumpkin, which gently bobbed up and down with the motion of the waves. At that moment it was quite out of Tip's reach, but after a time it floated nearer and still nearer until the boy was able to reach it with his pole and draw it to the shore. Then he brought it to the top of the bank, carefully wiped the water from its pumpkin face with his handkerchief, and ran with it to Jack and replaced the head upon the man's neck.

There are four illustrations of Jack with his head detached.

The Sawhorse (who really is very disagreeable) has more complaints:

"I'll have nothing more to do with that Pumpkinhead," declared the Saw-Horse, viciously. "he loses his head too easily to suit me."

Jack is constantly worried about the perishability of his head:

“I am in constant terror of the day when I shall spoil."

"Nonsense!" said the Emperor — but in a kindly, sympathetic tone. "Do not, I beg of you, dampen today's sun with the showers of tomorrow. For before your head has time to spoil you can have it canned, and in that way it may be preserved indefinitely."

At one point he suggests using up a magical wish to prevent his head from spoiling.

The Woggle-Bug rather heartlessly observes that Jack's head is edible:

“I think that I could live for some time on Jack Pumpkinhead. Not that I prefer pumpkins for food; but I believe they are somewhat nutritious, and Jack's head is large and plump."

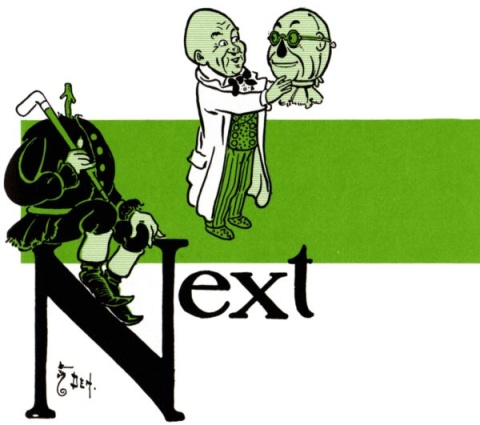

At one point, the Scarecrow is again disassembled:

Meanwhile the Scarecrow was taken apart and the painted sack that served him for a head was carefully laundered and restuffed with the brains originally given him by the great Wizard.

There is an illustration of this process, with the Scarecrow's trousers going through a large laundry-wringer; perhaps they sent his head through later.

The protagonists need to escape house arrest in a palace, and they assemble a flying creature, which they bring to life with the same magical charm that animated Jack and the Sawhorse. For the creature's head:

The Woggle-Bug had taken from its position over the mantle-piece in the great hallway the head of a Gump. … The two sofas were now bound firmly together with ropes and clothes-lines, and then Nick Chopper fastened the Gump's head to one end.

Once brought to life, the Gump is extremely puzzled:

“The last thing I remember distinctly is walking through the forest and hearing a loud noise. Something probably killed me then, and it certainly ought to have been the end of me. Yet here I am, alive again, with four monstrous wings and a body which I venture to say would make any respectable animal or fowl weep with shame to own.”

Flying in the Gump thing, the Woggle-Bug he cautions Jack:

"Not unless you carelessly drop your head over the side," answered the Woggle-Bug. "In that event your head would no longer be a pumpkin, for it would become a squash."

and indeed, when the Gump crash-lands, Jack's head is again in peril:

Jack found his precious head resting on the soft breast of the Scarecrow, which made an excellent cushion…

Whew. But the peril isn't over; it must be protected from a flock of jackdaws, in an unusual double-decaptitation:

[The Scarecrow] commanded Tip to take off Jack's head and lie down with it in the bottom of the nest… Nick Chopper then took the Scarecrow to pieces (all except his head) and scattered the straw… completely covering their bodies.

Shortly after, Jack's head must be extricated from underneath the Gump's body, where it has rolled. And the jackdaws have angrily scattered all the Scarecrow's straw, leaving him nothing but his head:

"I really think we have escaped very nicely," remarked the Tin Woodman, in a tone of pride.

"Not so!" exclaimed a hollow voice.

At this they all turned in surprise to look at the Scarecrow's head, which lay at the back of the nest.

"I am completely ruined!" declared the Scarecrow…

They re-stuff the Scarecrow with banknotes.

At the end of the book, the Gump is again disassembled:

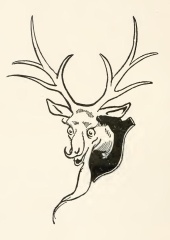

“Once I was a monarch of the forest, as my antlers fully prove; but now, in my present upholstered condition of servitude, I am compelled to fly through the air—my legs being of no use to me whatever. Therefore I beg to be dispersed."

So Ozma ordered the Gump taken apart. The antlered head was again hung over the mantle-piece in the hall…

It reminds me a bit of Dixie Flatline. I wonder if Baum was famillar with that episode? But unlike Dixie, the head lives on, as heads in Oz are wont to do:

You might think that was the end of the Gump; and so it was, as a flying-machine. But the head over the mantle-piece continued to talk whenever it took a notion to do so, and it frequently startled, with its abrupt questions, the people who waited in the hall for an audience with the Queen.

The Gump's head makes a brief reappearance in the fourth book, startling Dorothy with an abrupt question.

Ozma of Oz

Oz fans will have been anticipating this section, which is a highlight on any tour of the Disembodied Heads of Oz. For it features the Princess Langwidere:

Now I must explain to you that the Princess Langwidere had thirty heads—as many as there are days in the month.

I hope you're buckled up.

But of course she could only wear one of them at a time, because she had but one neck. These heads were kept in what she called her "cabinet," which was a beautiful dressing-room that lay just between Langwidere's sleeping-chamber and the mirrored sitting-room. Each head was in a separate cupboard lined with velvet. The cupboards ran all around the sides of the dressing-room, and had elaborately carved doors with gold numbers on the outside and jewelled-framed mirrors on the inside of them.

When the Princess got out of her crystal bed in the morning she went to her cabinet, opened one of the velvet-lined cupboards, and took the head it contained from its golden shelf. Then, by the aid of the mirror inside the open door, she put on the head—as neat and straight as could be—and afterward called her maids to robe her for the day. She always wore a simple white costume, that suited all the heads. For, being able to change her face whenever she liked, the Princess had no interest in wearing a variety of gowns, as have other ladies who are compelled to wear the same face constantly.

Oh, but it gets worse. Foreshadowing:

After handing head No. 9, which she had been wearing, to the maid, she took No. 17 from its shelf and fitted it to her neck. It had black hair and dark eyes and a lovely pearl-and-white complexion, and when Langwidere wore it she knew she was remarkably beautiful in appearance.

There was only one trouble with No. 17; the temper that went with it (and which was hidden somewhere under the glossy black hair) was fiery, harsh and haughty in the extreme, and it often led the Princess to do unpleasant things which she regretted when she came to wear her other heads.

Langwidere and Dorothy do not immediately hit it off. And then the meeting goes completely off the rails:

"You are rather attractive," said the lady, presently. "Not at all beautiful, you understand, but you have a certain style of prettiness that is different from that of any of my thirty heads. So I believe I'll take your head and give you No. 26 for it."

Dorothy refuses, and after a quarrel, the Princess imprisons her in a tower.

Ozma of Oz contains only this one head-related episode, but I think it surpasses the other books in the quality of the writing and the interest of the situation.

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz

This loser of a book has no disembodied heads, only barely a threat of one. Eureka the Pink Kitten has been accused of eating one of the Wizard's tiny trained piglets.

[Ozma] was just about to order Eureka's head chopped off with the Tin Woodman's axe…

The Wizard does shoot a Gargoyle in the eye with his revolver, though.

The Road to Oz

In this volume the protagonists fall into the hands of the Scoodlers:

It had the form of a man, middle-sized and rather slender and graceful; but as it sat silent and motionless upon the peak they could see that its face was black as ink, and it wore a black cloth costume made like a union suit and fitting tight to its skin. …

The thing gave a jump and turned half around, sitting in the same place but with the other side of its body facing them. Instead of being black, it was now pure white, with a face like that of a clown in a circus and hair of a brilliant purple. The creature could bend either way, and its white toes now curled the same way the black ones on the other side had done.

"It has a face both front and back," whispered Dorothy, wonderingly; "only there's no back at all, but two fronts."

Okay, but I promised disembodied heads. The Scoodlers want to make the protagonists into soup. When Dorothy and the others try to leave, the Scoodlers drive them back:

Two of them picked their heads from their shoulders and hurled them at the shaggy man with such force that he fell over in a heap, greatly astonished. The two now ran forward with swift leaps, caught up their heads, and put them on again, after which they sprang back to their positions on the rocks.

The problem with this should be apparent.

The characters escape from their prison and, now on guard for flying heads, they deal with them more effectively than before:

The shaggy man turned around and faced his enemies, standing just outside the opening, and as fast as they threw their heads at him he caught them and tossed them into the black gulf below. …

They should have taken a hint from the Hammer-Heads, who clearly have the better strategy. If you're going to fling your head at trespassers, you should try to keep it attached somehow.

Presently every Scoodler of the lot had thrown its head, and every head was down in the deep gulf, and now the helpless bodies of the creatures were mixed together in the cave and wriggling around in a vain attempt to discover what had become of their heads. The shaggy man laughed and walked across the bridge to rejoin his companions.

Brutal.

That is the only episode of head-detachment that we actually see. The shaggy man and Button Bright have their heads changed into a donkey's head and a fox's head, respectively, but manage to keep them attached. Jack Pumpkinhead makes a return, to explain that he need not have worried about his head spoiling:

I've a new head, and this is the fourth one I've owned since Ozma first made me and brought me to life by sprinkling me with the Magic Powder."

"What became of the other heads, Jack?"

"They spoiled and I buried them, for they were not even fit for pies. Each time Ozma has carved me a new head just like the old one, and as my body is by far the largest part of me I am still Jack Pumpkinhead, no matter how often I change my upper end.

He now lives in a pumpkin field, so as to be assured of a ready supply of new heads.

The Emerald City of Oz

By this time Baum was getting tired of Oz, and it shows in the lack of decapitations in this tired book.

In one of the two parallel plots, the ambitious General Guph promises the Nome King that he will conquer Oz. Realizing that the Nome armies will be insufficient, he hires three groups of mercenaries. The first of these aren't quite headless, but:

These Whimsies were curious people who lived in a retired country of their own. They had large, strong bodies, but heads so small that they were no bigger than door-knobs. Of course, such tiny heads could not contain any great amount of brains, and the Whimsies were so ashamed of their personal appearance and lack of commonsense that they wore big heads, made of pasteboard, which they fastened over their own little heads.

Don't we all know someone like that?

To induce the Whimsies to fight for him, Guph promises:

"When we get our Magic Belt," he made reply, "our King, Roquat the Red, will use its power to give every Whimsie a natural head as big and fine as the false head he now wears. Then you will no longer be ashamed because your big strong bodies have such teenty-weenty heads."

The Whimsies hold a meeting and agree to help, except for one doubter:

But they threw him into the river for asking foolish questions, and laughed when the water ruined his pasteboard head before he could swim out again.

While Guph is thus engaged, Dorothy and her aunt and uncle are back in Oz sightseeing. One place they visit is the town of Fuddlecumjig. They startle the inhabitants, who are “made in a good many small pieces… they have a habit of falling apart and scattering themselves around…”

The travelers try to avoid startling the Fuddles, but they are unsuccessful, and enter a house whose floor is covered with little pieces of the Fuddles who live there.

On one [piece] which Dorothy held was an eye, which looked at her pleasantly but with an interested expression, as if it wondered what she was going to do with it. Quite near by she discovered and picked up a nose, and by matching the two pieces together found that they were part of a face.

"If I could find the mouth," she said, "this Fuddle might be able to talk, and tell us what to do next."

They do succeed in assembling the rest of the head, which has red hair:

"Look for a white shirt and a white apron," said the head which had been put together, speaking in a rather faint voice. "I'm the cook."

This is fortunate, since it is time for lunch.

Jack Pumpkinhead makes an appearance later, but his head stays on his body.

The Patchwork Girl of Oz

As far as I can tell, there are no decapitations in this book. The closest we come is an explanation of Jack Pumpkinhead's head-replacement process:

“Just now, I regret to say, my seeds are rattling a bit, so I must soon get another head."

"Oh; do you change your head?" asked Ojo.

"To be sure. Pumpkins are not permanent, more's the pity, and in time they spoil. That is why I grow such a great field of pumpkins — that I may select a new head whenever necessary."

"Who carves the faces on them?" inquired the boy.

"I do that myself. I lift off my old head, place it on a table before me, and use the face for a pattern to go by. Sometimes the faces I carve are better than others--more expressive and cheerful, you know--but I think they average very well."

Some people the protagonists meet in their travels use the Scarecrow as sports equipment, but his head remains attached to the rest of him.

Tik-tok of Oz

This is a pretty good book, but there are no disembodied heads that I could find.

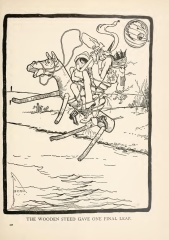

The Scarecrow of Oz

As you might guess from the title, the Scarecrow loses his head again. Twice.

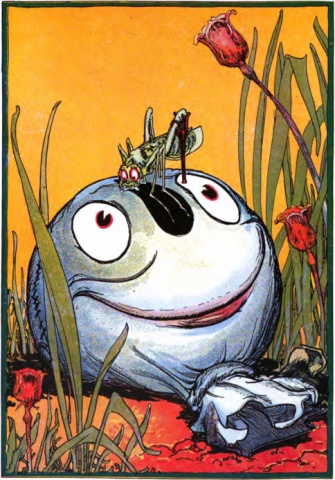

Only a short time elapsed before a gray grasshopper with a wooden leg came hopping along and lit directly on the upturned face of the Scarecrow’s head.

The Scarecrow and the grasshopper (who is Cap'n Bill, under an enchantment) have a philosophical conversation about whether the Scarecrow can be said to be alive, and a little later Trot comes by and reassembles the Scarecrow. Later he nearly loses it again:

… the people thought they would like him for their King. But the Scarecrow shook his head so vigorously that it became loose, and Trot had to pin it firmly to his body again.

The Scarecrow is not yet out of danger. In chapter 22 he falls into a waterfall and his straw is ruined. Cap'n Bill says:

“… the best thing for us to do is to empty out all his body an’ carry his head an’ clothes along the road till we come to a field or a house where we can get some fresh straw.”

This they do, with the disembodied head of the Scarecrow telling stories and giving walking directions.

Rinkitink in Oz

No actual heads are lost in the telling of this story. Prince Inga kills a giant monster by bashing it with an iron post, but its head (if it even has one; it's not clear) remains attached. Rinkitink sings a comic song about a man named Ned:

A red-headed man named Ned was dead;

Sing fiddle-cum-faddle-cum-fi-do!

In battle he had lost his head;

Sing fiddle-cum-faddle-cum-fi-do!

'Alas, poor Ned,' to him I said,

'How did you lose your head so red?'

Sing fiddle-cum-faddle-cum-fi-do!

But Ned does not actually appear in the story, and we only get to hear the first two verses of the song because Bilbil the goat interrupts and begs Rinkitink to stop.

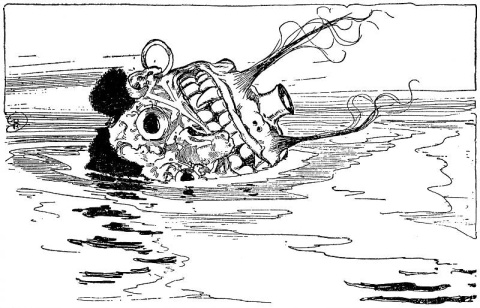

Elsewhere, Nikobob the woodcutter faces a monster named Choggenmugger, hacks off its tongue with his axe, splits its jaw in two, and then chops it into small segments, “a task that proved not only easy but very agreeable”. But there is no explicit removal of its head and indeed, the text and the pictures imply that Choggenmugger is some sort of giant sausage and has no head to speak of.

The Lost Princess of Oz

No disembodied heads either. The nearest we come is:

At once there rose above the great wall a row of immense heads, all of which looked down at them as if to see who was intruding.

These heads, however, are merely the heads of giants peering over the wall.

Two books in a row with no disembodied heads. I am becoming discouraged. Perhaps this project is not worth finishing. Let's see, what is coming next?

Oh.

Right then…

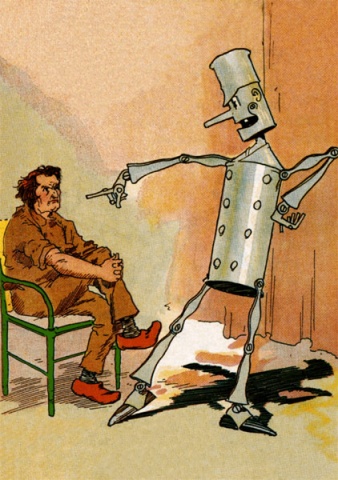

The Tin Woodman of Oz

This is the mother lode of decapitations in Oz. As you may recall, in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz the Tin Woodman relates how he came to be made of tin. He dismembered himself with a cursed axe, and after amputating all four of his limbs, he had them replaced with tin prostheses:

The Wicked Witch then made the axe slip and cut off my head, and at first I thought that was the end of me. But the tinsmith happened to come along, and he made me a new head out of tin.

One would expect that they threw the old head into a dumpster. But no! In The Tin Woodman of Oz we learn that it is still hanging around:

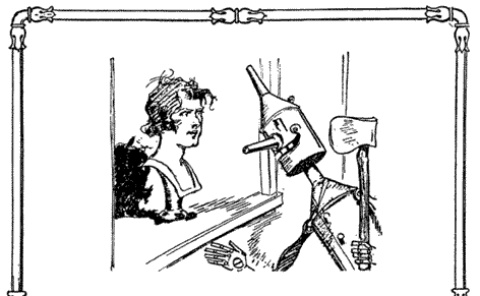

The Tin Woodman had just noticed the cupboards and was curious to know what they contained, so he went to one of them and opened the door. There were shelves inside, and upon one of the shelves which was about on a level with his tin chin the Emperor discovered a Head—it looked like a doll's head, only it was larger, and he soon saw it was the Head of some person. It was facing the Tin Woodman and as the cupboard door swung back, the eyes of the Head slowly opened and looked at him. The Tin Woodman was not at all surprised, for in the Land of Oz one runs into magic at every turn.

"Dear me!" said the Tin Woodman, staring hard. "It seems as if I had met you, somewhere, before. Good morning, sir!"

"You have the advantage of me," replied the Head. "I never saw you before in my life."

This creepy scene is more amusing than I remembered:

"Haven't you a name?"

"Oh, yes," said the Head; "I used to be called Nick Chopper, when I was a woodman and cut down trees for a living."

"Good gracious!" cried the Tin Woodman in astonishment. "If you are Nick Chopper's Head, then you are Me—or I'm You—or—or— What relation are we, anyhow?"

"Don't ask me," replied the Head. "For my part, I'm not anxious to claim relationship with any common, manufactured article, like you. You may be all right in your class, but your class isn't my class. You're tin."

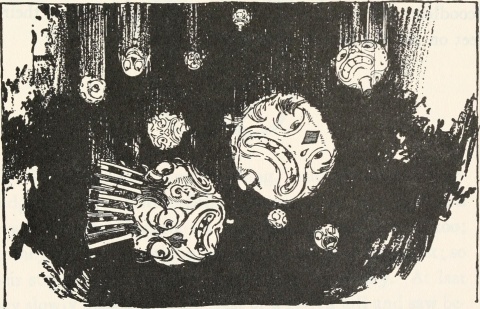

Apparently Neill enjoyed this so much that he illustrated it twice, once as a full-page illustration and once as a spot illustration on the first page of the chapter:

The chapter, by the way, is titled “The Tin Woodman Talks to Himself”.

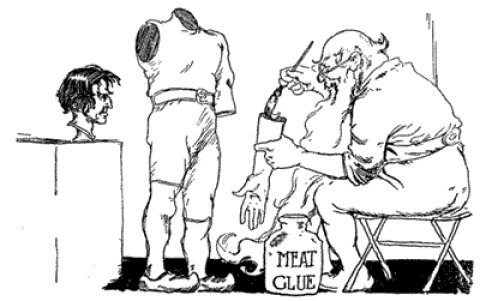

Later, we get the whole story from Ku-Klip, the tinsmith who originally assisted the amputated Tin Woodman. Ku-Klip explains how he used leftover pieces from the original bodies of both the Tin Woodman and the Tin Soldier (a completely superfluous character whose backstory is identical to the Woodman's) to make a single man, called Chopfyt:

"First, I pieced together a body, gluing it with the Witch's Magic Glue, which worked perfectly. That was the hardest part of my job, however, because the bodies didn't match up well and some parts were missing. But by using a piece of Captain Fyter here and a piece of Nick Chopper there, I finally got together a very decent body, with heart and all the trimmings complete."

The Tin Soldier is spared the shock of finding his own head in a closet, since Ku-Klip had used it in Chopfyt.

I'm sure you can guess where this is going.

Whew, that was quite a ride. Fortunately we are near the end and it is all downhill from here.

The Magic of Oz

This book centers around Kiki Aru, a grouchy Munchkin boy who discovers an extremely potent magical charm for transforming creatures. There are a great many transformations in the book, some quite peculiar and humiliating. The Wizard is turned into a fox and Dorothy into a lamb. Six monkeys are changed into giant soldiers. There is a long episode in which Trot and Cap'n Bill are trapped on an enchanted island, with roots growing out of their feets and into the ground. A giraffe has its tail bitten off, and there is the usual explanation about Jack Pumpkinhead's short shelf life. But I think everyone keeps their heads.

Glinda of Oz

There are no decapitations in this book, so we will have to settle for a consolation prize. The book's plot concerns the political economy of the Flatheads.

Dorothy knew at once why these mountain people were called Flatheads. Their heads were really flat on top, as if they had been cut off just above the eyes and ears.

The Flatheads carry their brains in cans. This is problematic: an ambitious flathead has made himself Supreme Dictator, and appropriated his enemies’ cans for himself.

The protagonists depose the Supreme Dictator, and Glinda arranges for each Flathead to keep their own brains in their own head where they can't be stolen, in a scene reminiscent of when the Scarecrow got his own brains, way back when.

That concludes our tour of the Disembodied Heads of Oz. Thanks for going on this journey with me.

[ Previously, Frank Baum's uncomfortable relationship with Oz. Coming up eventually, an article on domestic violence in Oz. Yes, really ]

[Other articles in category /book] permanent link