Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | J |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

In this section:

| Another use for strace (groff) |

| Another use for strace (isatty) |

| Easy exhaustive search with the list monad |

| I'm old |

| Your kids will love a cookie-decorating party |

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Fri, 24 Apr 2015

Easy exhaustive search with the list monad

(Haskell people may want to skip this article about Haskell, because the technique is well-known in the Haskell community.)

Suppose you would like to perform an exhaustive search. Let's say for concreteness that we would like to solve this cryptarithm puzzle:

S E N D

+ M O R E

-----------

M O N E Y

This means that we want to map the letters S, E, N, D, M,

O, R, Y to distinct digits 0 through 9 to produce a five-digit

and two four-digit numerals which, when added in the indicated way,

produce the indicated sum.

(This is not an especially difficult example; my 10-year-old daughter Katara was able to solve it, with some assistance, in about 30 minutes.)

If I were doing this in Perl, I would write up either a recursive descent search or a solution based on a stack or queue of partial solutions which the program would progressively try to expand to a full solution, as per the techniques of chapter 5 of Higher-Order Perl. In Haskell, we can use the list monad to hide all the searching machinery under the surface. First a few utility functions:

import Control.Monad (guard)

digits = [0..9]

to_number = foldl (\a -> \b -> a*10 + b) 0

remove rs ls = foldl remove' ls rs

where remove' ls x = filter (/= x) ls

to_number takes a list of digits like [1,4,3] and produces the

number they represent, 143. remove takes two lists and returns all

the things in the second list that are not in the first list. There

is probably a standard library function for this but I don't remember

what it is. This version is !!O(n^2)!!, but who cares.

Now the solution to the problem is:

-- S E N D

-- + M O R E

-- ---------

-- M O N E Y

solutions = do

s <- remove [0] digits

e <- remove [s] digits

n <- remove [s,e] digits

d <- remove [s,e,n] digits

let send = to_number [s,e,n,d]

m <- remove [0,s,e,n,d] digits

o <- remove [s,e,n,d,m] digits

r <- remove [s,e,n,d,m,o] digits

let more = to_number [m,o,r,e]

y <- remove [s,e,n,d,m,o,r] digits

let money = to_number [m,o,n,e,y]

guard $ send + more == money

return (send, more, money)

Let's look at just the first line of this:

solutions = do

s <- remove [0] digits

…

The do notation is syntactic sugar for

(remove [0] digits) >>= \s -> …

where “…” is the rest of the block. To expand this further, we need

to look at the overloading for >>= which is implemented differently

for every type. The mote on the left of >>= is a list value, and

the definition of >>= for lists is:

concat $ map (\s -> …) (remove [0] digits)

where “…” is the rest of the block.

So the variable s is bound to each of 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 in turn, the

rest of the block is evaluated for each of these nine possible

bindings of s, and the nine returned lists of solutions are combined

(by concat) into a single list.

The next line is the same:

e <- remove [s] digits

for each of the nine possible values for s, we loop over nine value

for e (this time including 0 but not including whatever we chose for

s) and evaluate the rest of the block. The nine resulting lists of

solutions are concatenated into a single list and returned to the

previous map call.

n <- remove [s,e] digits

d <- remove [s,e,n] digits

This is two more nested loops.

let send = to_number [s,e,n,d]

At this point the value of send is determined, so we compute and

save it so that we don't have to repeatedly compute it each time

through the following 300 loop executions.

m <- remove [0,s,e,n,d] digits

o <- remove [s,e,n,d,m] digits

r <- remove [s,e,n,d,m,o] digits

let more = to_number [m,o,r,e]

Three more nested loops and another computation.

y <- remove [s,e,n,d,m,o,r] digits

let money = to_number [m,o,n,e,y]

Yet another nested loop and a final computation.

guard $ send + more == money

return (send, more, money)

This is the business end. I find guard a little tricky so let's

look at it slowly. There is no binding (<-) in the first line, so

these two lines are composed with >> instead of >>=:

(guard $ send + more == money) >> (return (send, more, money))

which is equivalent to:

(guard $ send + more == money) >>= (\_ -> return (send, more, money))

which means that the values in the list returned by guard will be

discarded before the return is evaluated.

If send + more == money is true, the guard expression yields

[()], a list of one useless item, and then the following >>= loops

over this one useless item, discards it, and returns yields a list

containing the tuple (send, more, money) instead.

But if send + more == money is false, the guard expression yields

[], a list of zero useless items, and then the following >>= loops

over these zero useless items, never runs return at all, and yields

an empty list.

The result is that if we have found a solution at this point, a list

containing it is returned, to be concatenated into the list of all

solutions that is being constructed by the nested concats. But if

the sum adds up wrong, an empty list is returned and concated

instead.

After a few seconds, Haskell generates and tests 1.36 million choices for the eight bindings, and produces the unique solution:

[(9567,1085,10652)]

That is:

S E N D 9 5 6 7

+ M O R E + 1 0 8 5

----------- -----------

M O N E Y 1 0 6 5 2

It would be an interesting and pleasant exercise to try to implement

the same underlying machinery in another language. I tried this in

Perl once, and I found that although it worked perfectly well, between

the lack of the do-notation's syntactic sugar and Perl's clumsy

notation for lambda functions (sub { my ($s) = @_; … } instead of

\s -> …) the result was completely unreadable and therefore

unusable. However, I suspect it would be even worse in Python

because of semantic limitations of that language. I would be

interested to hear about this if anyone tries it.

[ Addendum: Thanks to Tony Finch for pointing out the η-reduction I missed while writing this at 3 AM. ]

[ Addendum: Several people so far have misunderstood the question

about Python in the last paragraph. The question was not to implement

an exhaustive search in Python; I had no doubt that it could be done

in a simple and clean way, as it can in Perl. The question was to

implement the same underlying machinery, including the list monad

and its bind operator, and to find the solution using the list

monad.

[ Peter De Wachter has written in with a Python solution that clearly demonstrates that the problems I was worried about will not arise, at least for this task. I hope to post his solution in the next few days. ]

[ Addendum 20150803: De Wachter's solution and one in Perl ]

[Other articles in category /prog/haskell] permanent link

Tue, 21 Apr 2015

Another use for strace (isatty)

(This is a followup to an earlier article describing an interesting use of strace.)

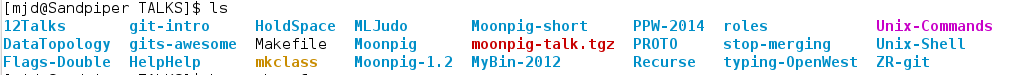

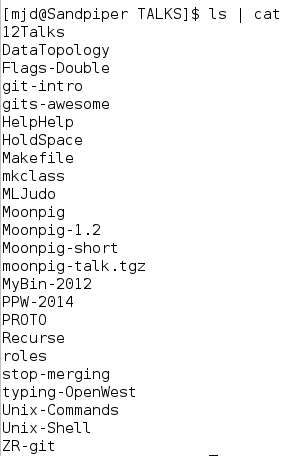

A while back I was writing a talk about Unix internals and I wanted to

discuss how the ls command does a different display when talking to

a terminal than otherwise:

ls to a terminal

ls not to a terminal

How does ls know when it is talking to a terminal? I expect that is

uses the standard POSIX function isatty. But how does isatty find

out?

I had written down my guess. Had I been programming in C, without

isatty, I would have written something like this:

@statinfo = stat STDOUT;

if ( $statinfo[2] & 0060000 == 0020000

&& ($statinfo[6] & 0xff) == 5) { say "Terminal" }

else { say "Not a terminal" }

(This is Perl, written as if it were C.) It uses fstat (exposed in

Perl as stat) to get the mode bits ($statinfo[2]) of the inode

attached to STDOUT, and then it masks out the bits the determine if

the inode is a character device file. If so, $statinfo[6] is the

major and minor device numbers; if the major number (low byte) is

equal to the magic number 5, the device is a terminal device. On my

current computers the magic number is actually 136. Obviously this

magic number is nonportable. You may hear people claim that those bit

operations are also nonportable. I believe that claim is mistaken.

The analogous code using isatty is:

use POSIX 'isatty';

if (isatty(STDOUT)) { say "Terminal" }

else { say "Not a terminal" }

Is isatty doing what I wrote above? Or something else?

Let's use strace to find out. Here's our test script:

% perl -MPOSIX=isatty -le 'print STDERR isatty(STDOUT) ? "terminal" : "nonterminal"'

terminal

% perl -MPOSIX=isatty -le 'print STDERR isatty(STDOUT) ? "terminal" : "nonterminal"' > /dev/null

nonterminal

Now we use strace:

% strace -o /tmp/isatty perl -MPOSIX=isatty -le 'print STDERR isatty(STDOUT) ? "terminal" : "nonterminal"' > /dev/null

nonterminal

% less /tmp/isatty

We expect to see a long startup as Perl gets loaded and initialized,

then whatever isatty is doing, the write of nonterminal, and then

a short teardown, so we start searching at the end and quickly

discover, a couple of screens up:

ioctl(1, SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE or TCGETS, 0x7ffea6840a58) = -1 ENOTTY (Inappropriate ioctl for device)

write(2, "nonterminal", 11) = 11

write(2, "\n", 1) = 1

My guess about fstat was totally wrong! The actual method is that

isatty makes an ioctl call; this is a device-driver-specific

command. The TCGETS parameter says what command is, in this case

“get the terminal configuration”. If you do this on a non-device, or

a non-terminal device, the call fails with the error ENOTTY. When

the ioctl call fails, you know you don't have a terminal. If you do

have a terminal, the TCGETS command has no effects, because it is a

passive read of the terminal state. Here's the successful call:

ioctl(1, SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE or TCGETS, {B38400 opost isig icanon echo ...}) = 0

write(2, "terminal", 8) = 8

write(2, "\n", 1) = 1

The B38400 opost… stuff is the terminal configuration; 38400 is the baud rate.

(In the past the explanatory text for ENOTTY was the mystifying “Not

a typewriter”, even more mystifying because it tended to pop up when

you didn't expect it. Apparently Linux has revised the message to the

possibly less mystifying “Inappropriate ioctl for device”.)

(SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE is mentioned because apparently someone decided

to give their SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE operation, whatever that is, the

same numeric code as TCGETS, and strace isn't sure which one is

being requested. It's possible that if we figured out which device was

expecting SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE, and redirected standard output to

that device, that isatty would erroneously claim that it was a

terminal.)

[ Addendum 20150415: Paul Bolle has found that the

SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE pertains to the old and possibly deprecated OSS

(Open Sound System)

It is conceivable that isatty would yield the wrong answer when

pointed at the OSS /dev/dsp or /dev/audio device or similar. If

anyone is running OSS and willing to give it a try, please contact me at mjd@plover.com. ]

[ Addendum 20191201: Thanks to Hacker News user

jwilk for pointing

out that strace is

now able to distinguish TCGETS from SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE. ]

[Other articles in category /Unix] permanent link

Sun, 19 Apr 2015

Another use for strace (groff)

The marvelous Julia Evans is always looking for ways to express her

love of strace and now has written a zine about

it. I don't use

strace that often (not as often as I should, perhaps) but every once

in a while a problem comes up for which it's not only just the right

thing to use but the only thing to use. This was one of those

times.

I sometimes use the ancient Unix drawing language

pic. Pic has many

good features, but is unfortunately coupled too closely to the Roff

family of formatters (troff, nroff, and the GNU project version,

groff). It only produces Roff output, and not anything more

generally useful like SVG or even a bitmap. I need raw images to

inline into my HTML pages. In the past I have produced these with a

jury-rigged pipeline of groff, to produce PostScript, and then GNU

Ghostscript (gs) to translate the PostScript to a PPM

bitmap, some PPM utilities to crop and

scale the result, and finally ppmtogif or whatever. This has some

drawbacks. For example, gs requires that I set a paper size, and

its largest paper size is A0. This means that large drawings go off

the edge of the “paper” and gs discards the out-of-bounds portions.

So yesterday I looked into eliminating gs. Specifically I wanted to

see if I could get groff to produce the bitmap directly.

GNU groff has a -Tdevice option that specifies the "output"

device; some choices are -Tps for postscript output and -Tpdf for

PDF output. So I thought perhaps there would be a -Tppm or

something like that. A search of the manual did not suggest anything

so useful, but did mention -TX100, which had something to do with

100-DPI X window system graphics. But when I tried this groff only said:

groff: can't find `DESC' file

groff:fatal error: invalid device `X100`

The groff -h command said only -Tdev use device dev. So what

devices are actually available?

strace to the rescue! I did:

% strace -o /tmp/gr groff -Tfpuzhpx

and then a search for fpuzhpx in the output file tells me exactly

where groff is searching for device definitions:

% grep fpuzhpx /tmp/gr

execve("/usr/bin/groff", ["groff", "-Tfpuzhpx"], [/* 80 vars */]) = 0

open("/usr/share/groff/site-font/devfpuzhpx/DESC", O_RDONLY) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

open("/usr/share/groff/1.22.2/font/devfpuzhpx/DESC", O_RDONLY) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

open("/usr/lib/font/devfpuzhpx/DESC", O_RDONLY) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

I could then examine those three directories to see if they existed, and if so find out what was in them.

Without strace here, I would be reduced to groveling over the

source, which in this case is likely to mean trawling through the

autoconf output, and that is something that nobody wants to do.

Addendum 20150421: another article about strace. ]

[ Addendum 20150424: I did figure out how to prevent gs from

cropping my output. You can use the flag -p-P48i,48i to groff to

set the page size to 48 inches (48i) by 48 inches. The flag is

passed to grops, and then resulting PostScript file contains

%%DocumentMedia: Default 3456 3456 0 () ()

which instructs gs to pretend the paper size is that big. If it's

not big enough, increase 48i to 120i or whatever. ]

[Other articles in category /Unix] permanent link

Tue, 14 Apr 2015This week I introduced myself to Recurse Center, where I will be in residence later this month, and mentioned:

I have worked as a professional programmer for a long time so I sometimes know strange historical stuff because I lived through it.

Ms. Nikki Bee said she wanted to hear more. Once I got started I had trouble stopping.

I got interested in programming from watching my mom do it. I first programmed before video terminals were common. I still remember the smell of the greasy paper and the terminal's lubricating oil. When you typed control-G, the ASCII BEL character, a little metal hammer hit an actual metal bell that went "ding!".

I remember when there was a dedicated computer just for word processing; that's all it did. I remember when hard disks were the size of washing machines. I remember when you could buy magnetic cores on Canal Street, not far from where Recurse Center is now. Computer memory is still sometimes called “core”, and on Unix your program still dumps a core file if it segfaults. I've worked with programmers who were debugging core dumps printed on greenbar paper, although I've never had to do it myself.

I frequented dialup

BBSes before

there was an Internet. I remember when the domain name system was

rolled out. Until then email addresses looked like yuri@kremvax,

with no dots; you didn't need dots because each mail host had a unique

name. I read the GNU

Manifesto in its

original publication in Dr. Dobb's. I remember the day the Morris

Worm hit.

I complained to Laurence Canter after he and his wife perpetrated the first large scale commercial spamming of the Internet. He replied:

People in your group are interested. Why do you wish to deprive them of what they consider to be important information??

which is the same excuse used by every spammer since.

I know the secret history of the Java compiler, why Java 5.0 had generics even though Sun didn't want them, and why they couldn't get rid of them. I remember when the inventors of LiveScript changed its name to JavaScript in a craven attempt to borrow some of Java's buzz.

I once worked with Ted Nelson.

I remember when Sun decided they would start charging extra to ship C compilers with their hardware, and how the whole Internet got together to fund an improved version of the GNU C compiler that would be be free and much better than the old Sun compiler ever was.

I remember when NCSA had a web page, updated daily, called “What's New on the World Wide Web”. I think I was the first person to have a guest book page on the Web. I remember the great land rush of 1996 when every company woke up at the same time and realized it needed a web site.

I remember when if you were going to speak at a conference, you would mail a paper copy of your slides to the conference people a month before so they could print it into books to hand out to the attendees. Then you would photocopy the slides onto plastic sheets so you could display them on the projector when you got there. God help you if you spilled the stack of plastic right before the talk.

tl;dr i've been around a while.

However, I have never programmed in COBOL.

[ Addendum 20150609: I'm so old, I once attended a meeting at which Adobe was pitching their new portable document format. ]

(I'm not actually very old, but I got started very young.)

[Other articles in category /IT] permanent link

Wed, 01 Apr 2015

Your kids will love a cookie-decorating party

We had a party last week for Toph's 7th birthday, at an indoor rock-climbing gym, same as last year. Last year at least two of the guests showed up and didn't want to climb, so Lorrie asked me to help think of something for them to do if the same thing happened this year. After thinking about it, I decided we should have cookie decorating.

This is easy to set up and kids love it. I baked some plain sugar cookies, bought chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry frosting, several tubes of edible gel, and I mixed up five kinds of colored sugar. We had some colored sprinkles and little gold dragées and things like that. I laid the ingredients out on the table in the gym's side room with some plastic knives and paintbrushes, and the kids who didn't want to climb, or who wanted a break from climbing, decorated cookies. It was a great success. Toph's older sister Katara had hurt her leg, and couldn't climb, so she helped the littler kids with cookies. Even the tiny two-year-old sister of one of the guests was able to participate, and enjoyed playing with the dragées.

(It's easy to vary the project depending on how much trouble you want to take. I made the cookies from scratch, which is pretty easy, but realized later I could have bought prefabricated cookie batter, which would have been even easier. The store sold colored sugar for $3.29 for four ounces, which is offensive, so I went home and made my own. You put one drop of food coloring per two ounces of sugar in a sealed container and shake it up for a minute, for a total cost of close to zero; Toph helped with this. I bought my frosting, but when my grandmother used to do it she'd make a simple white frosting from confectioners' sugar and then color it with food coloring.)

I was really pleased with the outcome, and not just because the guests liked it, but also because it is a violation of gender norms for a man to plan a cookie-decorating activity and then bake the cookies and prepare the pastel-colored sugar and so forth. (And of course I decorated some cookies myself.) These gender norms are insidious and pervasive, and to my mind no opportunity to interfere with them should be wasted. Messing with the gender norms is setting a good example for the kids and a good example for other dads and for the rest of the world.

I am bisexual, and sometimes I feel that it doesn't affect my life very much. The sexual part is mostly irrelevant now; I fell in love with a woman twenty years ago and married her and now we have kids. I probably won't ever have sex with another man. Whatever! In life you make choices. My life could have swung another way, but it didn't.

But there's one part of being bisexual that has never stopped paying dividends for me, and that is that when I came out as queer, it suddenly became apparent to me that I had abandoned the entire gigantic structure of how men are supposed to behave. And good riddance! This structure belongs in the trash; it completely sucks. So many straight men spend a huge amount of time terrified that other straight men will mock them for being insufficiently manly, or mocking other straight men for not being sufficiently manly. They're constantly wondering "if I do this will the other guys think it's gay?" But I've already ceded that argument. The horse is out of the barn, and I don't have to think about it any more. If people think what I'm doing is gay, that's a pill I swallowed when I came out in 1984. If they say I'm acting gay I'll say "close, but actually, I'm bi, and go choke on a bag of eels, jackass."

You don't have to be queer to opt out of straight-guy bullshit, and I think I would eventually have done it anyway, but being queer made opting out unavoidable. When I was first figuring out being queer I spent a lot of time rethinking my relationship to society and its gender constructions, and I felt that I was going to have to construct my own gender from now and that I no longer had the option of taking the default. I wasn't ever going to follow Rule Number One of Being a Man (“do not under any circumstances touch, look at, mention, or think about any dick other than your own”), so what rules was I going to follow? Whenever someone tried to pull “men don't” on me, (or whenever I tried to pull it on myself) I'd immediately think of all the Rule Number One stuff I did that “men don't” and it would all go in the same trash bin. Where (did I say this already?) it belongs.

Opting out frees up a lot of mental energy that I might otherwise waste worrying about what other people think of stuff that is none of their business, leaving me more space to think about how I feel about it and whether I think it's morally or ethically right and whether it's what I want. It means that if someone is puzzled or startled by my pink sneakers, I don't have to care, except I might congratulate myself a little for making them think about gender construction for a moment. Or the same if people find out I have a favorite flower (CROCUSES YEAH!) or if I wash the dishes or if I play with my daughters or watch the ‘wrong’ TV programs or cry or apologize for something I did wrong or whatever bullshit they're uncomfortable about this time.

Opting out frees me up to be a feminist; I don't have to worry that a bunch of men think I'm betraying The Team, because I was never on their lousy team in the first place.

And it frees me up to bake cookies for my kid's birthday party, to make a lot of little kids happy, and to know that that can only add to, not subtract from, my identity. I'm Dominus, who loves programming and mathematics and practicing the piano and playing with toy octopuses and decorating cookies with a bunch of delightful girls.

This doesn't have to be a big deal. Nobody is likely to be shocked or even much startled by Dad baking cookies. But these tiny actions, chipping away at these vile rules, are one way we take tiny steps toward a better world. Every kid at that party will know, if they didn't before, that men can and do decorate cookies.

And perhaps I can give someone else courage to ignore some of that same bullshit that prevents all of us from being as great as we could and should be, all those rules about stuff men aren't supposed to do and other stuff women aren't supposed to do, that make everyone less. I decided about twenty years ago that that was the best reason for coming out at all. People are afraid to be different. If I can be different, maybe I can give other people courage and comfort when they need to be different too. As a smart guy once said, you can be a light to the world, like a city on a hilltop that cannot be hidden.

And to anyone who doesn't like it, I say:

[Other articles in category /misc] permanent link