Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | J |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Sun, 07 Feb 2016

I've read a bunch of 19-century English novels lately. I'm not exactly sure why; it just sort of happened. But it's been a lot of fun. When I was small, my mother told me more than once that people often dislike these books because they are made to read them too young; the books were written for adult readers and don't make sense to children. I deliberately waited to read most of these, and I am very pleased now to find that now that I am approaching middle age I enjoy books that were written for people approaching middle age.

Spoilers abound.

Jane Eyre

This is one of my wife's favorite books, or perhaps her very favorite, but I had not read it before. Wow, it's great! Jane is as fully three-dimensional as anyone in fiction.

I had read The Eyre Affair, which unfortunately spoiled a lot of the plot for me, including the Big Shocker; I kept wondering how I would feel if I didn't know what was coming next. Fortunately I didn't remember all the details.

From her name, I had expected Blanche Ingram to be pale and limp; I was not expecting a dark, disdainful beauty.

When Jane tells Rochester she must leave, he promises to find her another position, and the one he claims to have found is hilariously unattractive: she will be the governess to the five daughters of Mrs. Dionysus O'Gall of Bitternutt Lodge, somewhere in the ass-end of Ireland.

What a thrill when Jane proclaims “I am an independent woman now”! But she has achieved this by luck; she inherited a fortune from her long-lost uncle. That was pretty much the only possible path, and it makes an interesting counterpoint to Vanity Fair, which treats some of the same concerns.

The thought of dutifully fulfilling the duty of a dutiful married person by having dutiful sex with the dutiful Mr. Rivers makes my skin crawl. I imagine that Jane felt the same way.

Mr. Brocklehurst does not get one-tenth of what he deserves.

Jane Eyre set me off on a Victorian novel kick. The preface of Jane Eyre praises William Thackeray and Vanity Fair in particular. So I thought I'd read some Thackeray and see how I liked that. Then for some reason I read Silas Marner instead of Vanity Fair. I'm not sure how that happened.

Silas Marner

Silas Marner was the big surprise of this batch of books. I don't know why I had always imagined Silas Marner would be the very dreariest and most tedious of all Victorian novels. But Silas Marner is quite short, and I found it very sweet and charming.

I do not suppose my Gentle Readers are as likely to be familiar with Silas Marner as with Jane Eyre. As a young man, Silas is a member of a rigid, inward-looking religious sect. His best friend frames him for a crime, and he is cast out. Feeling abandoned by society and by God, he settles in Raveloe and becomes a miser, almost a hermit. Many years pass, and his hoarded gold is stolen, leaving him bereft. But one snowy evening a two-year-old girl stumbles into his house and brings new purpose to his life. I have omitted the subplot here, but it's a good subplot.

One of the scenes I particularly enjoyed concerns Silas’ first (and apparently only) attempt to discipline his adopted two-year-old daughter Eppie, with whom he is utterly besotted. Silas knows that sooner or later he will have to, but he doesn't know how—striking her seems unthinkable—and consults his neighbors. One suggests that he shut her in the dark, dirty coal-hole by the fireplace. When Eppie wanders away one day, Silas tries to be stern.

“Eppie must go into the coal hole for being naughty. Daddy must put her in the coal hole.”

He half expected that this would be shock enough and that Eppie would begin to cry. But instead of that she began to shake herself on his knee as if the proposition opened a pleasing novelty.

As they say, no plan survives contact with the enemy.

Seeing that he must proceed to extremities, he put her into the coal hole, and held the door closed, with a trembling sense that he was using a strong measure. For a moment there was silence but then came a little cry “Opy, opy!” and Silas let her out again…

Silas gets her cleaned up and changes her clothes, and is about to settle back to his work

when she peeped out at him with black face and hands again and said “Eppie in de toal hole!”

Two-year-olds are like that: you would probably strangle them, if they weren't so hilariously cute.

Everyone in this book gets what they deserve, except the hapless Nancy Lammeter, who gets a raw deal. But it's a deal partly of her own making. As Thackeray says of Lady Crawley, in a somewhat similar circumstance, “a title and a coach and four are toys more precious than happiness in Vanity Fair”.

There is a chapter about a local rustics at the pub which may remind you that human intercourse could be plenty tiresome even before the invention of social media. The one guy who makes everything into an argument will be quite familiar to my Gentle Readers.

I have added Silas Marner to the long list of books that I am glad I was not forced to read when I was younger.

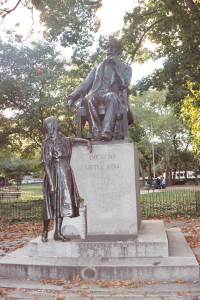

The Old Curiosity Shop

Unlike Silas Marner, I know why I read this one. In the park near my house is a statue of Charles Dickens and Little Nell, on which my daughter Toph is accustomed to climb. As she inevitably asked me who it was a statue of, I explained that Dickens was a famous writer, and Nell is a character in a book by Dickens. She then asked me what the book was about, and who Nell was, and I did not know. I said I would read the book and find out, so here we are.

My experience with Dickens is very mixed. Dickens was always my mother's number one example of a writer that people were forced to read when too young. My grandfather had read me A Christmas Carol when I was young, and I think I liked it, but probably a lot of it went over my head. When I was about twenty-two I decided to write a parody of it, which meant I had to read it first, but I found it much better than I expected, and too good to be worth parodying. I have reread it a couple of times since. it is very much worth going back to, and is much better than its many imitators.

I had been required to read Great Expectations in high school, had not cared for it, and had stopped after four or five chapters. But as an adult I kept a copy in my house for many years, waiting for the day when I might try again, and when I was thirty-five I did try again, and I loved it.

Everyone agrees that Great Expectations is one of Dickens’ best, and so it is not too surprising that I was much less impressed with Martin Chuzzlewit when I tried that a couple of years later. I remember liking Mark Tapley, but I fell off the bus shortly after Martin came to America, and I did not get back on.

A few years ago I tried reading The Pickwick Papers, which my mother said should only be read by middle-aged people, and I have not yet finished it. It is supposed to be funny, and I almost never find funny books funny, except when they are read aloud. (When I tell people this, they inevitably name their favorite funny books: “Oh, but you thought The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was funny, didn't you?” or whatever. Sorry, I did not. There are a few exceptions; the only one that comes to mind is Stanisław Lem's The Cyberiad, which splits my sides every time. SEVEN!

Anyway, I digress. The Old Curiosity Shop was extremely popular when it was new. You always hear the same two stories about it: that crowds assembled at the wharves in New York to get spoilers from the seamen who might have read the new installments already, and that Oscar Wilde once said “one must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.” So I was not expecting too much, and indeed The Old Curiosity Shop is a book with serious problems.

Chief among them: it was published in installments, and about a third of the way through writing it Dickens seems to have changed his mind about how he wanted it to go, but by then it was too late to go back and change it. There is Nell and her grandfather on the one hand, the protagonists, and the villain is the terrifying Daniel Quilp. It seems at first that Nell's brother Fred is going to be important, but he disappears and does not come back until the last page when we find out he has been dead for some time. It seems that Quilp's relations with his tyrannized wife are going to be important, but Quilp soon moves out of his house and leaves Mrs. Quilp more or less alone. It seems that Quilp is going to pursue the thirteen-year-old Nell sexually, but Nell and Grandpa flee in the night and Quilp never meets them again. They spend the rest of the book traveling from place to place not doing much, while Quilp plots against Nell's friend Kit Nubbles.

Dickens doesn't even bother to invent names for many of the characters. There is Nell’s unnamed grandfather; the old bachelor; the kind schoolmaster; the young student; the guy who talks to the fire in the factory in Birmingham; and the old single gentleman.

The high point of the book for me was the development of Dick Swiveller. When I first met Dick I judged him to be completely worthless; we later learn that Dick keeps a memorandum book with a list of streets he must not go into, lest he bump into one of his legion of creditors. But Dick turns out to have some surprises in him. Quilp's lawyer Sampson Brass is forced to take on Swiveller as a clerk, in furtherment of Quilp's scheme to get Swiveller married to Nell, another subplot that comes to nothing. While there, Swiveller, with nothing to amuse himself, teaches the Brasses’ tiny servant, a slave so starved and downtrodden that she has never been given a name, to play cribbage. She later runs away from the Brasses, and Dick names her Sophronia Sphynx, which he feels is “euphonious and genteel, and furthermore indicative of mystery.” He eventually marries her, “and they played many hundred thousand games of cribbage together.”

I'm not alone in finding Dick and Sophronia to be the most interesting part of The Old Curiosity Shop. The anonymous author of the excellent blog A Reasonable Quantity of Butter agrees with me, and so does G.K. Chesterton:

The real hero and heroine of The Old Curiosity Shop are of course Dick Swiveller and [Sophronia]. It is significant in a sense that these two sane, strong, living, and lovable human beings are the only two, or almost the only two, people in the story who do not run after Little Nell. They have something better to do than to go on that shadowy chase after that cheerless phantom.

Today is Dickens’ 204th birthday. Happy birthday, Charles!

Vanity Fair

I finally did get to Vanity Fair, which I am only a quarter of the way through. It seems that Vanity Fair is going to live or die on the strength of its protagonist Becky Sharp.

When I first met Ms. Sharp, I thought I would love her. She is independent, clever, and sharp-tongued. But she quickly turned out to be scheming, manipulative, and mercenary. She might be hateful if the people she was manipulating were not quite such a flock of nincompoops and poltroons. I do not love her, but I love watching her, and I partly hope that her schemes succeed, although I rather suspect that she will sabotage herself and undo all her own best plans.

Becky, like Jane Eyre, is a penniless orphan. She wants money, and in Victorian England there are only two ways for her to get it: She can marry it or inherit it. Unlike Jane, she does not have a long-lost wealthy uncle (at least, not so far) so she schemes to get it by marriage. It's not very creditable, but one can't feel too righteous about it; she is in the crappy situation of being a woman in Victorian England, and she is working hard to make the best of it. She is extremely cynical, but the disagreeable thing about a cynic is that they refuse to pretend that things are better than they are. I don't think she has done anything actually wrong, and so far her main path to success has been to act so helpful and agreeable that everyone loves her, so I worry that I may come out of this feeling that Thackeray does not give her a fair shake.

In the part of the book I am reading, she has just married the exceptionally stupid Rawdon Crawley. I chuckle to I think of the flattering lies she must tell him when they are in the sack. She has married him because he is the favorite relative of his rich but infirm aunt. I wonder at this, because the plan does not seem up to Becky’s standards: what if the old lady hangs on for another ten years? But perhaps she has a plan B that hasn't yet been explained.

Thackeray says that Becky is very good-looking, but in his illustrations she has a beaky nose and an unpleasant, predatory grin. In a recent film version she was played by Reese Witherspoon, which does not seem to me like a good fit. Although Becky is blonde, I keep picturing Aubrey Plaza, who always seems to me to be saying something intended to distract you from what she is really thinking.

I don't know yet if I will finish Vanity Fair—I never know if I will finish a book until I finish it, and I have at times said “fuck this” and put down a book that I was ninety-five percent of the way through—but right now I am eager to find out what happens next.

Blah blah blah

This post observes the tenth anniversary of this blog, which I started in January 2006, directly inspired by Steve Yegge’s rant on why You Should Write Blogs, which I found extremely persuasive. (Articles that appear to have been posted before that were backdated, for some reason that I no longer remember but would probably find embarrassing.) I hope my Gentle Readers will excuse a bit of navel-gazing and self-congratulation.

When I started the blog I never imagined that I would continue as long as I have. I tend to get tired of projects after about four years and I was not at all sure the blog would last even that long. But to my great surprise it is one of the biggest projects I have ever done. I count 484 published articles totalling about 450,000 words. (Also 203 unpublished articles in every possible state of incompletion.) I drew, found, stole, or otherwise obtained something like 1,045 diagrams and illustrations. There were some long stoppages between articles, but I always came back to it. And I never wrote out of obligation or to meet a deadline, but always because the spirit moved me to write.

Looking back on the old articles, I am quite pleased with the blog and with myself. I find it entertaining and instructive. I like the person who wrote it. When I'm reading articles written by other people it sometimes happens that I smile ruefully and wish that I had been clever enough to write that myself; sometimes that happens to me when I reread my own old blog articles, and then my smile isn't rueful.

The blog paints a good picture, I think, of my personality, and of the kinds of things that make me unusual. I realized long long ago that I was a lot less smart than many people. But the way in which I was smart was very different from the way most smart people are smart. Most of the smart people I meet are specialists, even ultra-specialists. I am someone who is interested in a great many things and who strives for breadth of knowledge rather than depth. I want to be the person who makes connections that the specialists are too nearsighted to see. That is the thing I like most about myself, and that comes through clearly in the blog. I know that if my twenty-five-year-old self were to read it, he would be delighted to discover that he would grow up to be the kind of person that he wanted to be, that he did not let the world squash his individual spark. I have changed, but mostly for the better. I am a much less horrible person than I was then: the good parts of the twenty-five-year-old’s personality have developed, and the bad ones have shrunk a bit. I let my innate sense of fairness and justice overcome my innate indifference to other people’s feelings, and I now treat people less callously than before. I am still very self-absorbed and self-satisfied, still delighted above all by my own mind, but I think I do a better job now of sharing my delight with other people without making them feel less.

My grandparents had Eliot and Thackeray on the shelf, and I was always intrigued by them. I was just a little thing when I learned that George Eliot was a woman. When I asked about these books, my grandparents told me that they were grown-up books and I wouldn't like them until I was older—the implication being that I would like them when I was older. I was never sure that I would actually read them when I was older. Well, now I'm older and hey, look at that: I grew up to be someone who reads Eliot and Thackeray, not out of obligation or to meet a deadline, but because the spirit moves me to read.

Thank you Grandma Libby and Grandpa Dick, for everything. Thank you, Gentle Readers, for your kind attention and your many letters through the years.

[Other articles in category /book] permanent link