Mark Dominus (陶敏修)

mjd@pobox.com

Archive:

| 2026: | J |

| 2025: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2024: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2023: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2022: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2021: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2020: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2019: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2018: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2017: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2016: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2015: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2014: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2013: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2012: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2011: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2010: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2009: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2008: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2007: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2006: | JFMAMJ |

| JASOND | |

| 2005: | OND |

Subtopics:

| Mathematics | 245 |

| Programming | 100 |

| Language | 95 |

| Miscellaneous | 75 |

| Book | 50 |

| Tech | 49 |

| Etymology | 35 |

| Haskell | 33 |

| Oops | 30 |

| Unix | 27 |

| Cosmic Call | 25 |

| Math SE | 25 |

| Law | 22 |

| Physics | 21 |

| Perl | 17 |

| Biology | 16 |

| Brain | 15 |

| Calendar | 15 |

| Food | 15 |

Comments disabled

Fri, 01 May 2020

More about Sir Thomas Urquhart

I don't have much to add at this point, but when I looked into Sir Thomas Urquhart a bit more, I found this amazing article by Denton Fox in London Review of Books. It's a review of a new edition of Urquhart's 1652 book The Jewel (Ekskybalauron), published in 1984. The whole article is worth reading. It begins:

Sir Thomas Urquhart … must have been a most peculiar man.

and then oh boy, does it deliver. So much of this article is quotable that I'm not sure what to quote. But let's start with:

The little we know about Urquhart’s early life comes mostly from his own pen, and is therefore not likely to be true.

Some excerpts will follow. You may enjoy reading the whole thing.

Trissotetras

I spent much way more time on this than I expected. Fox says:

In 1645 he brought out the Trissotetras … . Urquhart’s biographer, Willcock, says that ‘no one is known to have read it or to have been able to read it,’ …

Thanks to the Wonders of the Internet, a copy is available, and I have been able to glance at it. Urquhart has invented a microlanguage along the lines of Wilkins’ philosophical language, in which the words are constructed systematically. But the language of Trissotetras has a very limited focus: it is intended only for expressing statements of trigonometry. Urquhart says:

The novelty of these words I know will seeme strange to some, and to the eares of illiterate hearers sound like termes of Conjuration: yet seeing that since the very infancie of learning, such inventions have beene made use of, and new words coyned, …

The sentence continues for another 118 words but I think the point is made: the idea is not obviously terrible.

Here is an example of Urquhart's trigonometric language in action:

The second axiom is Eproso, that is, the sides are proportionall to one another as the sines of their opposite angles…

A person skilled in the art might be able to infer the meaning of this axiom from its name:

- E — a side

- Pro – proportional

- S – the sine

- O – the opposite angle

That is, a side (of a triangle) is proportional to the sine of the opposite angle. This principle is currently known as the law of sines.

Urquhart's idea of constructing mnemonic nonsense words for basic laws was not a new one. There was a long-established tradition of referring to forms of syllogistic reasoning with constructed mnemonics. For example a syllogism in “Darii” is a deduction of this form:

- All mammals have hair

- Some animals are mammals

- Therefore some animals have hair.

The ‘A’ in “Darii” is a mnemonic for the “all” clause and the ‘I’s for the “some” clauses. By memorizing a list of 24 names, one could remember which of the 256 possible deductions were valid.

Urquhart is following this well-trodden path and borrows some of its terminology. But the way he develops it is rather daunting:

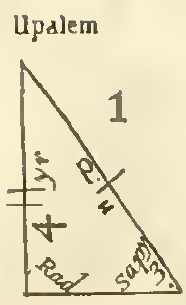

The Directory of this second Axiome is Pubkegdaxesh, which declareth that there are seven Enodandas grounded on it, to wit, foure Rectangular, Upalem, Ubeman, Ekarul, Egalem, and three Obliquangular, Danarele, Xemenoro, and Shenerolem.

I think that ‘Pubkegdaxesh’ is compounded from the initial syllables of the seven enodandas, with p from upalem, ub from ubamen, k from ekarul, eg from egalem, and so on. I haven't been able to decipher any of these, although I didn't try very hard. There are many difficulties. Sometimes the language is obscure because it's obsolete and sometimes because Urquhart makes up his own words. (What does “enodandas” mean?)

Let's just take “Upalem”. Here are Urquhart's glosses:

- U – the Subtendent side

- P – Opposite, whether Angle or side

- A — an angle

- L — the secant

- E — a side

- M — A tangent complement

I believe “a tangent complement” is exactly what we would now call a cotangent; that is, the tangent of the complementary angle. But how these six items relate to one another, I do not know.

Here's another difficulty: I'm not sure that ‘al’ is one component or two. It might be one:

- U – the Subtendent side

- P – Opposite, whether Angle or side

- Al — half

- E — a side

- M — A tangent complement

Either way I'm not sure what is meant. Wait, there is a helpful diagram, and an explanation of it:

The first figure, Vale, hath but one mood, and therefore of as great extent as it selfe, which is Upalem; whose nature is to let us know, when a plane right angled triangle is given us to resolve, who subtendent and one of the obliques is proposed, and one of the ambients required, that we must have recourse unto its resolver, which being Rad—U—Sapy ☞ Yr sheweth, that if we joyne the artificiall sine of the angle opposite to the side demanded with the Logarithm of the subtendent, the summe searched in the canon of absolute numbers will afford us the Logarithm of the side required.

This is unclear but tantalizing. Urquhart is solving a problem of elementary plane trigonometry. Some of the sides and angles are known, and we are to find one of the unknown ones. I think if if I read the book from the beginning I think I might be able to make out better what Urquhart was getting at. Tempting as it is I am going to abandon it here.

Trissotetras is dedicated to Urquhart's mother. In the introduction, he laments that

Trigonometry … hath beene hitherto exposed to the world in a method whose intricacy deterreth many from adventuring on it…

He must have been an admirer of Alexander Rosse, because the front matter ends with a little poem attributed to Rosse.

Pantochronachanon

Fox again:

Urquhart, with many others, was taken to London as a prisoner, where, apparently, he determined to recover his freedom and his estates by using his pen. His first effort was a genealogy in which he names and describes his ancestors, going back to Adam. … A modern reader might think this Urquhart’s clever trick to prove that he was not guilty by reason of insanity …

This is Pantochronachanon, which Wikipedia says “has been the subject of ridicule since the time of its first publication, though it was likely an elaborate joke”, with no citation given.

Fox mentions that Urquhart claims Alcibiades as one of his ancestors. He also claims the Queen of Sheba.

According to Pantochronachanon the world was created in 3948 BC (Ussher puts it in 4004), and Sir Thomas belonged to the 153rd generation of mankind.

The Jewel

Denton Fox:

Urquhart found it necessary to try again with the Jewel, or, to to give it its full title, which in some sense describes it accurately…

EKSKUBALAURON [Εκσκυβαλαυρον]: OR, The Discovery of A most exquisite Jewel, more precious then Diamonds inchased in Gold, the like whereof was never seen in any age; found in the kennel [gutter] of Worcester-streets, the day after the Fight, and six before the Autumnal Aequinox, anno 1651. Serving in this place, To frontal a Vindication of the honour of SCOTLAND, from that Infamy, whereinto the Rigid Presbyterian party of that Nation, out of their Covetousness and ambition, most dissembledly hath involved it.

Wowzers.

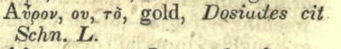

Fox claims that the title Εκσκυβαλαυρον means “from dung, gold” but I do not understand why he says this. λαύρα might be a sewer or privy, and I think the word σκυβα means garden herbs. (Addendum: the explanation.)

[The book] relates how… Urquhart’s lodgings were plundered, and over 3200 sheets of his writings, in three portmanteaux, were taken.… One should remember that there is not likely to be the slightest bit of truth in this story: it speaks well for the morality of modern scholars that so many of them should have speculated why Urquhart took all his manuscripts to war with him.

Fox says that in spite of the general interest in universal languages, “parts of his prospectus must have seemed absurd even then”, quoting this item:

Three and twentiethly, every word in this language signifieth as well backward as forward; and how ever you invert the letters, still shall you fall upon significant words, whereby a wonderful facility is obtained in making of anagrams.

Urquhart boasts that where other, presumably inferior languages have only five or six cases, his language has ten “besides the nominative”. I think Finnish has fourteen but I am not sure even the Finns would be so sure that more was better. Verbs in Urquhart's language have one of ten tenses, seven moods, and four voices. In addition to singular and plural, his language has dual (like Ancient Greek) and also ‘redual’ numbers. Nouns may have one of eleven genders. It's like a language designed by the Oglaf Dwarves.

A later item states:

This language affordeth so concise words for numbering, that the number for setting down, whereof would require in vulgar arithmetick more figures in a row then there might be grains of sand containable from the center of the earth to the highest heavens, is in it expressed by two letters.

and another item claims that a word of one syllable is capable of expressing an exact date and time down to the “half quarter of the hour”. Sir Thomas, I believe that Entropia, the goddess of Information Theory, would like a word with you about that.

Wrapping up

One final quote from Fox:

In 1658, when he must have been in his late forties, he sent a long and ornately abusive letter to his cousin, challenging him to a duel at a place Urquhart would later name,

quhich shall not be aboue ane hunderethe – fourtie leagues distant from Scotland.

If the cousin would neither make amends or accept the challenge, Urquhart proposed to disperse copies of his letter

over all whole the kingdome off Scotland with ane incitment to Scullions, hogge rubbers [sheep-stealers], kenell rakers [gutter-scavengers] – all others off the meanist sorte of rascallitie, to spit in yor face, kicke yow in the breach to tred on yor mushtashes ...

Fox says “Nothing much came of this, either.”.

I really wish I had made a note of what I had planned to say about Urquhart in 2008.

[ Addendum 20200502: Brent Yorgey has explained Εκσκυβαλαυρον for me. Σκύβαλα (‘skubala’) is dung, garbage, or refuse; it appears in the original Greek text of Philippians 3:8:

What is more, I consider everything a loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whose sake I have lost all things. I consider them garbage, that I may gain Christ…

And while the usual Greek word for gold is χρῡσός (‘chrysos’), the word αύρον (‘auron’, probably akin to Latin aurum) is also gold. The screenshot at right is from the 8th edition of Liddell and Scott. Thank you, M. Yorgey! ]

[Other articles in category /book] permanent link